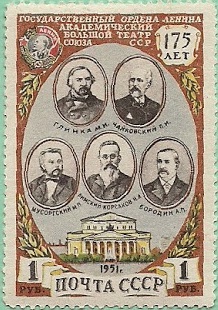

A 1951 stamp from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (CCCP in Russian, USSR in English) bears the images of five great Russian composers: Mikhail Glinka (top left), Peter Ilyitch Tchaikowsky (top right), Modest Moussorgsky (bottom left), Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakoff (bottom middle) and Alexander Borodin (bottom right).

Only one of them, however, can claim to be the first to link cholesterol to heart disease (10). Only one of them can claim to have developed the laboratory technique for joining fluorine atoms with carbon atoms, the discovery of which led the way to the development of Teflon-type plastics and Freon propellant (1,3). And nly one of them wrote musical compositions that won Broadway’s prestigious Antoinette Perry (“Tony”) award. Borodin.

Glinka is considered the first of the great Russian composers, the principal inspiration for those of his native land who followed, and his is some of the most wonderful music ever written. The exciting and beautiful overture to his opera, Ruslan and Ludmila, is performed regularly. Tchaikowsky, of course, is appropriately regarded as the greatest Russian composer and one of the greatest of all time. It is no exaggeration to say that Tchaikowsky’s music has, at one time or another and in one form or another, been heard by almost anyone who has a radio or a television or sees motion pictures. In the 1950’s the popular radio soap opera Road of Life opened each day, five days a week, with a theme taken from the exquisitively beautiful first movement of Tchaikowsky’s Symphony #6 in B minor (the Pathétique). Harold C. Schonburg, the foremost music critic of the mid-20th century, described Tchaikowsky’s music as a “sweet, inexhaustible, supersensuous fund of melody.” Mussorgsky, thanks to Disney’s 1940 film Fantasia and Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain, is known to millions. His Pictures at an Exhibition, whether in the original piano version or as orchestrated by Ravel, is one of the staples of the concert hall and classical music stations throughout the world. Similarly, Rimsky-Korsakov’s best known orchestral compositions – Scheherazade, Capriccio Espagnol, the Russian Easter Festival Overture – are recognized by millions of people and well known in the classical music repertoire.

The beautifully melodic compositions of Borodin, the physician and chemist, similar to the others, express a strongly nationalistic style of classical music but, in part because Borodin’s output was modest, his compositions are far less known and many have never even heard of his name.

Borodin’s life

Alexander Borodin was born in 1833, the illegitimate son of Prince Luka Stepanovich Gedianov and his mistress, Avdotya Konstantinova, a much younger woman (3-5,7-10,12,14-16). The boy was registered as the legal son of one of the Prince’s serfs, Porfiry Borodin, but the Prince cared for the boy at Alexander’s mother’s home. The Prince died when Borodin was only seven years old. Before he died, however, he granted freedom (serfdom was not outlawed in Russia until 1861) to the boy and provided him and his mother with sufficient financial resources.

Borodin’s mother was described as a highly intelligent woman (3,12). She devotedly provided her son with a thorough and classical education. At an early age Borodin exhibited a distinct talent for music, completing his first composition, a polka, when he was nine. He was an outstanding student with an excellent memory and a gift for languages. Early, he knew German, English and French in addition to Russian. In later life he would also learn Italian. He played the flute and the piano and later taught himself to play the cello. By the time he was 15 he composed several pieces of music.

He had another childhood passion – chemistry. He built a laboratory at home and experimented regularly.

In 1850 he enrolled in the Medico-Surgical Academy where he came under the influence of Professor Nikolai N. Zinin (1812-1880), Russia’s greatest chemist. Zinin was the first to synthesize aniline and his pioneering work in aniline derivatives led to the entire world of synthetic aniline dyes. Zinin also carried out research on nitroglycerine and Alfred Nobel (1833-1896) studied with him from age nine to 30, subsequently using his knowledge to develop explosives. After an accident with the highly unstable nitroglycerin killed his brother and others, Nobel went on to invent the more stable dynamite which made him a wealthy man. His wealth was used posthumously to endow the Nobel Prizes.

Borodin graduated cum eximia laude in 1855, at the age of 26.

Borodin the physician and scientist

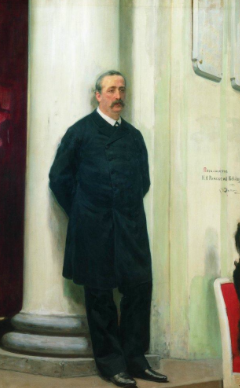

Alexander Borodin, seen in this portrait by Repin, was a practicing and well-regarded surgeon in the early years of his medical career but he was not happy as a clinician and devoted the greater part of his life to the study of chemistry. His musical career is all the more remarkable when considering that he was one of the leading scientists of his time and a leader of the St. Petersburg research community. During these early years he met Modest Mussorgsky, who was an officer of the Preobrazhensky Guards, one of Russia’s aristocratic regiments.

Borodin received a doctorate for his dissertation, “On the analogy of arsenic and phosphoric acids,” in 1858. The following year he, along with three colleagues, Ivan M. Sechenov (1829-1905), Sergei P. Botkin (1832-1889) and Dmitry I. Mendeleev (1834-1907), went abroad to gain experience. Zinin assured Borodin of an appointment as Adjunct Professor of Chemistry on his return. Mendeleev would go on to carry out groundbreaking research and develop the periodic table of elements, one of the fundamental tools of chemistry and physics. At this time Borodin decided to abandon his surgical career.

In Heidelberg, Borodin worked with one of Germany’s leading chemists, Robert Bunsen (1811-1899), but he was unhappy in that setting and, instead, he and his Russian colleagues, spent most of the time in the laboratory of Emil Erlenmeyer (1825-1909), remembered today mostly for the wide-bottomed laboratory flask he designed.

Cholesterol was first discovered in 1789, although its chemical structure was not elucidated until 1932. At a February 1871 meeting of the Russian Chemical Society (which Borodin helped found along with other chemists including Mendeleev) Borodin reported on work performed under his guidance by his assistant, Dr. Krylov. Borodin and Krylov expected their chemical analysis of the fat in heart muscles affected by fatty degeneration to yield glycerol. Instead they found cholesterol, the importance of which would not be understood for many years until the great Russian scientist and pathologist, Nikolai N. Anichkov, in 1913, fed rabbits diets rich in cholesterol with subsequent development of typical arterial atherosclerotic lesions (6, 11-13). Borodin and Krylov did not fully recognize the significance of their finding but, nonetheless, their data is the first evidence linking cholesterol to heart disease. The specific role of atherosclerosis in the development of heart disease remains controversial but that discussion is not for this article.

Borodin the composer

Borodin’s continuing musical activities were criticized by many of his colleagues, including and especially Professor Zinin who expected Borodin to be his successor. They saw in Borodin the makings a great chemist and felt sure he could not do both music and chemistry well.

In 1862 Mussorgsky introduced Borodin to Mily Balakirev (1836-1910), a mathematician, pianist, conductor and composer, remembered primarily for his promotion of Russian musical nationalism and also for his pivotal role in encouraging Tchaikowsky in his career. Balakirev became the head of a small group of young composers, including Mussorgsky, now retired from the military, Rimsky-Korsakov, a former naval cadet, Cesar Cui, an officer of the corps of engineers, and Borodin. Together they were known as “The Mighty Handful” and also were dubbed “The Five.” The group drew their inspiration from Russian folk music and especially from Glinka, regarded as the father of Russian classical music.

Despite his increasing musical activities Borodin still regarded his clinical, laboratory and teaching responsibilities as far more important than composing. Writing about music he said, “For me, it is only rest … which takes time from my serious business as a professor. I am absorbed in my affairs, my science, my academy and students. Men and women students are dear to me.” Rimsky-Korsakov, commenting on Borodin’s busy clinical life, his heavy teaching schedule, his research, the many meetings he attended, and “his apartment which looked like a hospital,” as well as his sickly wife, wrote, “My heart ached to see how a great genius wasted his time on such matters and could not accomplish his real work.”

To both Zinin and Mussorgsky, Borodin was unequivocally a genius – but they each referred to completely different realms of expression.

In 1868 Balakirev arranged for a private performance of Borodin’s First Symphony; it was not a success, at least in part because of Borodin’s inability to devote enough time to preparing and correcting the musical scores used for the performance. A year later, after considerable effort by Borodin to provide a flawless version, Balakirev conducted the work in public to great acclaim. In addition, four days after that concert, Borodin made several important scientific presentations to the Chemical Society.

Borodin’s international fame as a composer would come a decade later after he met Franz Liszt (1811-1886) (8). Liszt was particularly impressed by Borodin’s Second Symphony and became active in promoting Borodin’s work throughout Germany. Borodin and Liszt became close friends, corresponding regularly, and Borodin dedicated his beautiful symphonic sketch, In the Steppes of Central Asia, to Liszt. When Borodin traveled to France and Belgium he received great ovations and was very much treated as a celebrity.

Borodin’s family

In 1861 Borodin met Katerina S. Protopopova, a 29-year-old woman who had come to Heidelberg to be treated for tuberculosis. A highly educated woman, she was a brilliant pianist. On returning to Heidelberg after taking part in a congress of German chemists Borodin found Katerina, now his fiancée, seriously ill with tuberculosis. On advice of her physician they quickly left for the milder climate of Pisa where he continued his work with two well-known chemists. A year later, Katerina considerably improved, they arrived in St. Petersburg where he was appointed Adjunct Professor and began a series of lectures to the students of the Academy. His lectures were highly regarded and he became one of the students’ favorites. In 1863 Borodin and Katerina married. Despite her chronic ill health and despite having no children their marriage was described as quite happy. Borodin was described as a genial person, dreamy, sensitive and easy-going (7). His hospitality was famous and his house was often filled with students, friends and relatives. With his professional responsibilities, his music and his many other interests, he was “in a constant tornado of activity” (7).

He became full professor in 1864. Subsequently the Borodins adopted two girls: Liza Balaneva in 1869 and, soon after, Elena Guseva who married Alexander Dianin, a chemist who was Borodin’s younger associate and who eventually succeeded Borodin as chair of the chemistry department at the Medical-Surgical Academy.

Borodin’s role in the medical education of women

Borodin played was quite active in the administrative activities of the Medico-Surgical Academy and, in 1872, together with a number of colleagues, helped found the first medical course for women in Russia. This started out as a course in obstetrics but soon became a course of higher medical education for women with Borodin devoting considerable time to both the administration of the school and to teaching.

Under the reign of the relatively liberal and forward-thinking Tsar Alexander II the women’s medical college flourished. After being fatally wounded in a bombing. Alexander II was succeeded by the highly reactionary Alexander III. One of Alexander II’s last activities was to write to the Academy of Sciences with a design for a rocket-propelled airship that could rise above the earth’s atmosphere, decades before Robert Goddard (1882-1945).

Under Alexander III the Medico-Surgical Academy was renamed the Military Medical Academy and placed under the control of the Ministry of War. There were mass arrests of students, with Borodin doing all he could to help those who had been detained. The Minister of War refused to allow the use of the military hospital as an academic base for the women’s medical courses. For the next three years, 1882-1885, Borodin and others were able to restructure the course under the aegis of the Ministry of Education but it was ultimately closed by the authorities, greatly affecting Borodin who was said to have burst into tears.

In this period of turmoil devoted considerable time and energy to composing his great opera, Prince Igor, the most enduring portions of which are the Polovstian Dances.

Kismet

The musical score for Kismet, a prize-winning Broadway musical in 1954, was based almost entirely on a number of Borodin’s highly melodic compositions. The story came from a 1911 play by Edward Knobloch set in Baghdad in the time of the Arabian Nights and is about a wily poet who manages to talk himself out of trouble on multiple occasions and of the romance between his daughter and the young Caliph. The New York critics of the time did not think much of the show itself but it had great success because of the music.

Three of the most popular songs were “Stranger in Paradise,” whose melody is in the Polovtsian Dances of Borodin’s opera Prince Igor, “Baubles, bangles and beads” as well as “And this is my Beloved” can be found in the String Quarter #2. These songs were played over and over again on the radio and television and, at the time, I knew the words of all of them. Other compositions, including In the Steppes of Central Asia, the Symphonies #1 and #2, the String Quartet #1, and other sections of Prince Igor were used by Robert Wright and George Forrest to make up the remainder of the score.

More recently, the international stage hit Miss Saigon, composed by Claude-Michel Schonberg, has, as one of its most beautiful and haunting songs, “The American Dream,” which is also based on Borodin’s Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor (17).

Although there is no shortage of physicians and scientists who are talented musicians, only a few are renowned (2). Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738), the great Dutch physician, cultivated chamber music. Leopold Auenbrugger (1722-1809), who is considered one of the founders of modern medicine because he developed the technique of percussion (tapping on the surface of the chest or abdomen to determine the inner structure) wrote the libretto for Der Rauchfangekehrer (The Chimney Sweep), an opera composed by a Mozart contemporary, Antonio Salieri (1750-1825). Herman Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (1821-1894), inventor of the ophthalmoscope, was known to be an accomplished pianist as was the great Viennese surgeon Theodor Billroth (1829-1894), musicologist and music critic who was a lifelong friend and co-performer of Johannes Brahms (1833-1897). Hector Berlioz (1803-1869), the son and grandson of physicians, and himself a medical school graduate, is one of the great composers. In the 20th century the missionary physician Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965) was a great organist and outstanding interpreter of Bach.

Borodin’s death

Borodin did not complete Prince Igor. It remained to a number of friends, including Rimsky-Korsakov, to add the finishing touches. On February 14, 1887, after working at the piano, Borodin came into the laboratory with tears of joy in his eyes, having worked out the finale for Igor and feeling that it was one of the best things he had ever composed. Regrettably he never wrote it down, only keeping it in his head, as he prepared for a fancy dress ball to be held the next day.

On February 15, while at the ball, he suddenly collapsed and despite being in a room full of physicians from the academy he died. At autopsy it was shown that he had an aneurysm of a coronary artery which had ruptured, leading to hemopericardium (blood filling the pericardial sac) and cardiac tamponade (the pericardial sac is inflexible, as it fills with blood, the heart can not expand again after each contraction).

Borodin is buried in Tichvin cemetery, at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, in St. Petersburg. His grave is next to that of Glinka and close to that of Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikowsky.

Additional reading:

- Browne MW. The music in the lab. New York Times, July 28, 1987.

- Cerda JJ. Art in medicine: musicians, physicians and physician-musician. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association 1993;volume 104:pages 228-234.

- Davies PJ. Alexander Porfir’yevich Borodin (1833-187): composer, chemist, physician and social reformer. Journal of Medical Biography 1996;volume 3:pages 207-217.

- Dianin SA. Borodin. London: Oxford University Press, 1963.

- Eisenberg MM. Alexander Pophyrievich Borodin, 1833-1887. Journal of the History of Medicine 1960;volume 15:pages 78-81

- Finking G, Hanke H. Nikolaj Nikolajewitsch Anitschow (1885-1964) established the cholesterol-fed rabbit as a model for atherosclerosis research. Atherosclerosis 1997;volume 135:pages 1-7.

- Garland AK. Doctors Afield – Alexander Borodin. New England Journal of Medicine 1955;volume 252:pages 187-188.

- Harbets A. Borodin and Liszt. London: Digby Long & Co; 1895.

- Harmon SE. Alexander Borodin: medical educator, chemist, composer. Maryland Medical Journal 1997; volume 36:pages 445-450.

- Hood W. Alexander Borodin: multi-talented chemical pathologist. Bulletin Royal College of Pathologists 1004;volume 126:pages 31-32.

- Hood W. Was the composer Borodin the first to link cholesterol to heart disease? http://www.priory.com/homol/Borodin.htm

- Konstantinov IE. The life and death of Professor Alexander P. Borodin: surgeon, chemist, and great musician. Surgery 1998;volume 123:pages 606-616.

- Konstantinov IE, Mejevoi N, Anichkov NM. Nikolai N. Anichkov and his theory of atherosclerosis 2006;volume 33:pages 417-423.

- Ober WB. Alexander Borodin, M.D. (1833-1887) – Physician, chemist and composer. New York State Journal of Medicine 1967;volume 67:pages 836-845.

- Sarton G. Borodin (1833-87). Osiris 1936;volume 7:page 225.

- Steinberg C, Kauffman GB. Alexander Porfire’vich Borodin: A Chemist’s Biography (English translation). 1988, Berlin, Springer-Verlag.

- Wall RL. Miss Saigon; play it again, Claude-Michel. The New York Times, June 9, 1991.

September 28, 2014 at 1:11 am

Impressive site and comprehensive blog post-I hope you’re enjoying this new project!

Email me-Mentors@HerMentorCenter.com if you’re interested in doing a Virtual Book Tour in December.

September 28, 2014 at 1:45 am

Steve,

This is wonderful. Very scholarly piece of writing. Thank you for sharing this.

Gil

September 28, 2014 at 4:27 pm

Thanks for including me. A wonderful, informative read. I’ve sent copies to my daughter and granddaughter who will appreciate it. Caitlin, our eldest granddaughter is currently studying History of Science in graduate school at Harvard. Best wishes, Bob Van de Velde

September 28, 2014 at 5:29 pm

lots of research, well done. Borodin was quite a guy!

September 28, 2014 at 7:09 pm

terrific story. thanks for sending it along. john

September 28, 2014 at 9:41 pm

Hi Steve,

I want to thank you for this delightful biography of Borodin. His music is what I call “receptor” music. You light it like a new flavor of ice cream. You don’t have to read program notes to be briefed on what you should listen to. Your receptors are pre-programed.

Best,

Max

October 21, 2014 at 6:30 pm

I look forward to reading this completely! I am saving it to read during my hospital stay for a knee revision; it will happen soon. Best regards!

November 27, 2015 at 5:31 am

A man of my heart.