The mostly unadorned, dark room slopes down from back to front. There’s room for perhaps 200 people but, as I soon learned, most stand and only about twenty people get to sit in the front, on the floor, on scattered cushions. The walls are rough painted and gray. A few old, wood-framed portraits of some of the past band members are hung carelessly around but it’s too dark to make out the features. In some photos they are holding a shiny trumpet or a sleek black clarinet or a slide trombone. Even though they don’t have names I recognize––a lot of the images don’t even have a name––you know they had the sound. Smoking was still acceptable when I was there and the room was thick with the slightly acrid smell of tobacco. The air was so heavy I wondered if the cilia of my respiratory epithelium were metaphorically gasping, knowing only a pathologist would think of that. It seems humidity never quite goes away in New Orleans smoke merging into mist.

carelessly around but it’s too dark to make out the features. In some photos they are holding a shiny trumpet or a sleek black clarinet or a slide trombone. Even though they don’t have names I recognize––a lot of the images don’t even have a name––you know they had the sound. Smoking was still acceptable when I was there and the room was thick with the slightly acrid smell of tobacco. The air was so heavy I wondered if the cilia of my respiratory epithelium were metaphorically gasping, knowing only a pathologist would think of that. It seems humidity never quite goes away in New Orleans smoke merging into mist.

Preservation Hall has been overpacked with people every time I’ve been there. The folks on the front cushions are always the most comfortable but the rest of us, standing tight against each other, are still happy to be there. I’ve never gotten there early enough to sit during the first few sets––in those days nobody chased you out and you could stay as long as you wanted––but once I managed to move to the front by staying around during quite a few breaks, gradually easing forward. Unfortunately, a lot of folks have the same idea and it did take a while. Narrow vestiges of aisles are at the sides and people are everywhere; leaning against the walls, eventually sitting and standing in the aisles, on the stage book-ending the players, even perching on the window sill behind the drummer and the trombone. Others, just hazy faces, are in the least clouded window panes, looking in, wide-eyed with the music. You know they can hear something, they move with the sound, but you also know it’s not quite enough. I’ve done that once; just stared in wanting to get closer and consoling myself with the occasional breeze that never makes it inside. You don’t have to wait long to get that window view but, after the one time I tried it, I preferred being inside with the band, despite the perspiration.

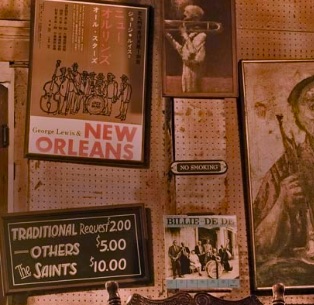

On the wall above the bass fiddle a worn old sign informs that you can request “traditional songs” for a dollar,  “others” for two, and “Saints” (The Saints go Marching In) for five. The prices have changed, I know they doubled but it has been a couple of decades since I was there and it’s probably more costly now to request the music you specially want to hear.

“others” for two, and “Saints” (The Saints go Marching In) for five. The prices have changed, I know they doubled but it has been a couple of decades since I was there and it’s probably more costly now to request the music you specially want to hear.

But maybe it’s not …

From the street, and behind the gate, there’s a sort of alley, the sign above it heralding the name.  Two doors lead into the Hall, one at the front and the other way back.

Two doors lead into the Hall, one at the front and the other way back.

Most people come in through the back door and patiently stand as the musicians––some of them decidedly old––shuffle in. There are many photographs of Preservation Hall on the internet showing the outside, the sign over the entrance, the bandstands and the players, but I haven’t been able to find one of the back of the Hall itself with the Dixieland Jazz lovers crunched together. My own photos are from the pre-digital era and are hidden away in one of a myriad of little yellow Kodachrome boxes.

The sound drenches you almost as much as the humidity. There’s no room for anything in your head other than that infectious music. The rhythm is unavoidable and can’t be tamed as it seeps into your head and your body. You soon feel like you’re glowing and, not too long after, you’re exhausted and exhilarated at the same time. The sound is as full at the back as the front and, if your feet aren’t too weary from walking the French Quarter, it’s pure joy to stand there as long as you can. Sometimes there’s somebody very tall in front of you and you can’t see the music-makers; all you get is the sound––that glorious beat, those high-flying notes––but that’s usually enough. No one ever complains.

The first time I saw Sweet Emma I was standing in the line outside with my colleague and friend, Lud Deppisch, waiting to be let in. We were in New Orleans for a pathology meeting in the late 1970’s. It was a long line and a sticky, hot night. An old black Buick sedan came up narrow St. Peter Street and stopped right in front of the Hall’s entrance. The line of cars behind grew longer and longer and the far-back ones began bleating their horns. A big, muscular, dark-skinned man got out of the driver’s seat, went to the trunk, unlocked it with a key and pulled out a folded wheelchair. He yanked it open with just one hand, completely oblivious to the traffic jam he had created, as well as to the increasingly awful honking. He pushed the chair to the passenger’s side and lifted a decidedly old, tiny, delicate, and quite feeble, black lady out. He gently nestled her in the chair and wheeled her into Preservation Hall. His movements were so smooth and effortless, she surely weighed less than feathers. Lud and I remarked how wonderful it was that they were bringing this weary, old, frail woman to hear great jazz. She looked so fragile we wondered if it was for the last time.

When we finally got inside, we found that slight and ancient old woman in full control of the piano. Sweet Emma Barrett was playing tonight!

Her hands moved faster than you could see. She was great, the perfect sounds dancing and twirling up from her fingers. The band was great. The music was great. It was a terrific night to be in Preservation Hall. Feet couldn’t hold still, heads couldn’t stop moving, hands had to clap.

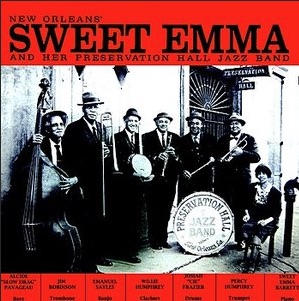

Four years later, another meeting in the “Big Easy”, “the city that time forgot,” and Sweet Emma was back at the keyboard at Preservation Hall. Fragile as she was the first time I heard her, she seemed mighty compared to this visit. Now she was a wisp, almost a shadow, almost a memory. This time she only played with her right hand as the twist of her face, the permanent grimace, gave testimony of a stroke. Perched on a thick pillow, her straw hat and red cap hung on the wall above the piano. You could see the hammers thudding against the exposed strings of the upright piano. That sign above the bass was still there––same prices as before––and a narrow shelf held a stereo record (vinyl) jacket bearing her name in large bold letters above a picture of her younger face. It was for sale when you finally headed out. It’s a great record. There are, as far as I can tell, six albums bearing her name and picture.

This was my fourth visit to Preservation Hall and some of the same players were still there. Old Emanuel Sayles was at the banjo, strumming away and making it sound like silver dollars falling together. A Segovia without a cello. He’d aged a lot since the last time I saw him but his special sound still sings as if he was just a kid. Shiny forehead, calm face, slightly quizzical smile. And fingers that dance faster on those strings than you can see. The tuba player this time was a big man––I’d never seen him before––still young and he didn’t seem to quite find that special something that’s been marinating in the Hall’s juices for so many decades. Maybe it’s not easy to squeeze those special sounds out of a tuba but then I think of the old children’s record, Tubby the Tuba––there are many versions but I think the Danny Kaye one of my childhood is still the best––and I can still hum the sweetest of melodies that Tubby was able to create; this fellow needs a few more years to get there. The bassist, also unfamiliar, had a leathery face, but his supple fingers urged deep, throbbing sounds from his big fiddle. Trombonist has been here before. He has a crown of thick white hair and he closes his eyes as he makes that slide croon sweet and long and low. The clarinet player, a very young blond man, is the surprise. When I was in the Hall the night before––I tended to end up there whenever I had a free evening––he didn’t play but only announced the breaks. This night he makes music so delicious, as if he had lived in Preservation Hall since he was in diapers, as if he had been making that magic ebony and silver stick sound sweet all his life.

But none of them holds on to the notes very long. They move the melody around. One effortlessly lays it down just as another picks it up. They toss it around, reeds to horns, drums to piano, strings back to reeds. Each caresses the song a little differently. A push bends the music, a pull heats it and cools it at the same time They each hold on to it long enough to give it a special identity––their own special identity––before letting go and handing it over again.

That’s jazz.

The audience listened with joy and reverence. With pure love. And when Sweet Emma played there was that extra hush. Three or four felt-heads seemed to strike the piano strings at the same instant. Her shoulders tilted ever so slightly, rocking back and forth, and the sound seemed to waft from the middle of her back. And then she sings, a half-tone louder than a whisper, raspy, a wounded sparrow barely able to chirp.

And the whole room stops breathing for a while.

Most of the people never heard her before, never even heard of her. Until she strikes her first note some look at her and think that somebody gave her the job out of pity. After she starts playing everyone knows she can hold her own, stroke or no stroke. Her peak days are so far gone some of the crowd weren’t even born. But there’s one or two, like the retired internist from Omaha crowded next me who shakes his head, half-smiles and says, “Man, you should have heard her when.” I nod with a full smile in agreement.

Still, here and now, we listen to every note because Sweet Emma is a hero. Sweet Emma is an explorer. She’s been to the Moon. To the Stars. And she’s still trying to bring us at least part of the way, as much as she can, along with her.

Emma Barrett was 85 when she died in 1983. She was born in New Orleans on March 25, 1897. A self-taught pianist and singer. But do you really have to be taught if you are from N’Orleens where the teaching is in the air, in the beignets, in the po’boys, the gumbo, in the water? In your mother’s milk?

She first worked with the Original Tuxedo Orchestra from 1923 until 1936, playing with some of the legendary jazz players of the time. In 1947 she accepted a regular job at Happy Landing, a local club in Peaniere, Louisiana, but she remained relatively unknown until 1961 when a recording that included her playing the piano and singing was released.

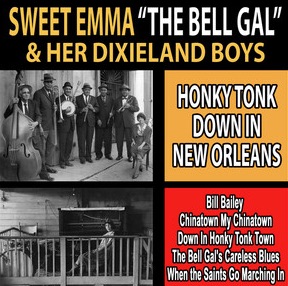

She was nicknamed “Bell Gal” because she wore a red skull cap and garters with tiny bells that jingled in time with  her music. In the album The Bell Gal and Her Dixieland Boys Music, Sweet Emma sings half the songs and leads two different groups. There’s a special joy, an exhilaration, when you play that record. If you catch the terrific 1965 film, The Cincinnati Kid, with riveting performances by Steve McQueen and the great actors Edward G. Robinson and Karl Malden, there’s a scene about 40 minutes into the film that features the Preservation Hall Jazz Band featuring Sweet Emma, red cap and all, singing and playing the piano.

her music. In the album The Bell Gal and Her Dixieland Boys Music, Sweet Emma sings half the songs and leads two different groups. There’s a special joy, an exhilaration, when you play that record. If you catch the terrific 1965 film, The Cincinnati Kid, with riveting performances by Steve McQueen and the great actors Edward G. Robinson and Karl Malden, there’s a scene about 40 minutes into the film that features the Preservation Hall Jazz Band featuring Sweet Emma, red cap and all, singing and playing the piano.

There’s a not-too flattering close-up of her, but it’s the music that stays with you.

There’s a not-too flattering close-up of her, but it’s the music that stays with you.

When we were in Las Vegas to see Lady Gaga we ate brunch with live Dixieland jazz in the background. It was good music, but it wasn’t Preservation Hall.

And there was no Sweet Emma.

Reference:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sweet_Emma_Barrett

February 11, 2019 at 7:55 pm

AS B4,VERY INTERESTING AND WELL WRITTEN

February 12, 2019 at 12:03 pm

Excellent. That first time you and Ludwig saw Emma, I also was in N.O.,but unfortunately did not care to go to P.H. I really missed something,…

February 12, 2019 at 5:31 pm

You painted the picture well. I never got to see her but nice revitalizing the memories of the hall.

February 13, 2019 at 7:49 am

Your descriptive ability is incredible.

I’m not really a jazz aficionado but your essay made me want to be in that room!

February 13, 2019 at 6:32 pm

great story telling. I also visited in the late 70’s and later(1980’s +) whenever in NO.

February 14, 2019 at 1:18 pm

Enjoyed your writing.