Ben Greene is the protagonist of my still-in-progress third novel. He is a senior pathologist (not a surprise …) and former chairman at a large academic hospital pathology department. Soon after his successor as chairman, Alden Morrison, arrives in the department a colleague and Greene’s close friend, Claude Dassin, dies unexpectedly after many months with a chronic debilitating neurologic disorder. That afternoon, at the request of Dassin’s wife, Ben helps a resident in the performance of the autopsy. At the completion, Ben calls Morrison to tell him the findings. Morrison listens but, instead of commenting on the surprise found at autopsy, changes the subject.

“Tell me.”

“Yes?”

“Dassin was your friend, wasn’t he?”

“Yes. Definitely,” now Ben’s voice quavered and, for the first time since Dassin died, his eyes got teary. His voice slightly rough and scratchy, he continued. “He was a good friend. Why are you asking?”

“Did you not have trouble doing the autopsy?”

What kind of question is that from a pathologist? Ben thought, but all he said was, “What kind of trouble?”

When Ben was a first-year resident, the very first autopsy he performed was on a physician with myasthenia gravis, an uncommon nerve and muscle disease. As they were starting Ben’s chief resident, Max Robbins, scalpel in hand, looked directly in Ben’s eyes and said, “Don’t forget that it’s an honor to autopsy another physician and a special honor if you are asked to perform an autopsy on another pathologist. You don’t have to do anything special for the case, you don’t have to treat them differently, but you should think about what I said, about the honor of caring for another physician. You are the last doctor for this other physician.” Ben hadn’t thought of this before but it immediately struck home and he did feel a special pride in what he was doing; lending his skills to the last stage of a fellow physician’s medical care. He felt, more than ever before, a part of the glorious tradition of medical practice. Over the years Ben participated in the performance of autopsies on more than a dozen medical staff members who died, a few of whom he knew well. He always passed Robbins’ message to the resident with whom he was working.

It had been the practice, when a physician died, for the chief resident to be the first to have the opportunity to perform the autopsy. When Ben was chief resident, Dr. Uyeda, one of the most revered teachers in the pathology program and a long-time smoker, suffered from increasingly severe emphysema at a time when treatment was only transiently useful. One afternoon, as Ben reviewed cases with him, Uyeda unbuttoned his shirtsleeve and yanked it up to have Ben feel a one-centimeter stony hard nodule under the skin of his forearm. Offering a diagnosis, the senior pathologist said, his Japanese accent still strong after more than fifty years in New York, “Calcifying epithelioma Malherbe.” Then, fixing his gaze on Ben’s eyes while rebuttoning his sleeve, he added, “When you do autopsy you make sure to confirm. Make sure to take this.” Ben was unable to immediately respond, his voice gone as he inhaled deeply, as he nodded his ascent.

Almost two months later, and two weeks after Uyeda’s death, Ben received the microscopic slides for the autopsy. Ben knew his teacher would be pleased with the care he had taken in performing the autopsy, would be proud of his abilities as he neared the end of his residency.

He also imagined Uyeda’s triumphant, slightly mischievous, grin when Ben confirmed the diagnosis of the benign skin lesion.

Now, Ben shakes his head and tells Morrison, “No, I didn’t have any trouble,” his words measured, wary now of the chairman’s perspective on their profession. “He was my friend. If I was a surgeon and he had appendicitis I would take out his appendix. I know how to do autopsies and I do them well,” he pauses and adds, “It was my privilege. I’ve done autopsies before on people I knew, including one of my teachers who gave me specific recommendations on things he wanted checked, wanted confirmed.” Ben hesitates, not wanting to share the story about Dr. Uyeda. “I hope,” he deliberately speaks slowly and slightly louder, “I hope that someone who knew me and valued me, someone who was my friend or my student, performs my autopsy.”

What does this have to do with Béla Schick and who was Béla (bay-la, not bella) Schick?

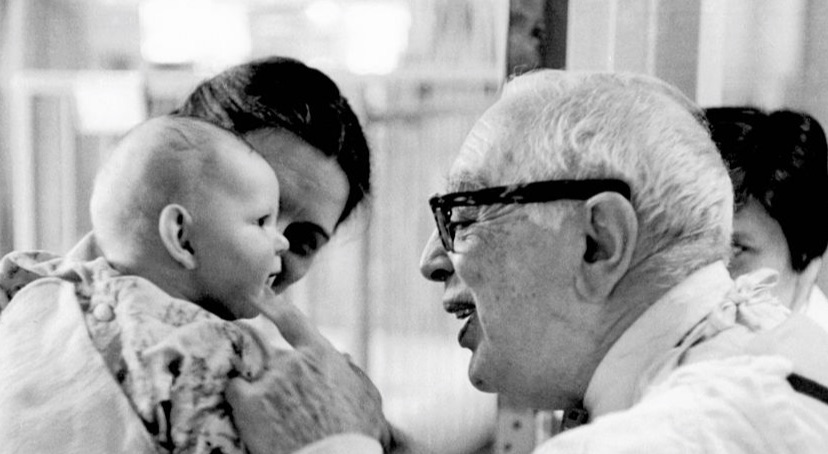

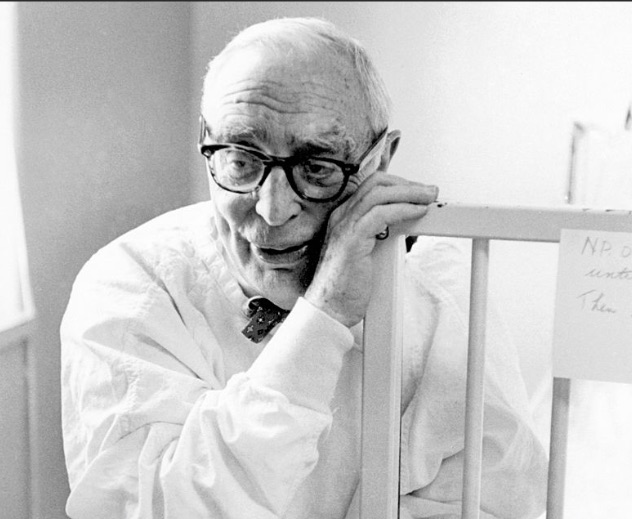

As I was writing that section of the novel I thought of Béla Schick. When I was a second-year resident I was privileged to help in the performance of the autopsy of Dr. Béla Schick, one of the most important figures in the history of medicine and, unhappily, one of the people forgotten by the public-at-large and by most physicians.

It is impossible to calculate the number of lives saved by Béla Schick’s great contribution: the Schick test for diphtheria.

Béla Schick said “First, the patient, second, the patient, third, the patient, fourth the patient, fifth the patient, and then maybe comes science. We first do everything for the patient; science can wait, research can wait.” Indeed, Schick’s ability to combine, in perfect harmony, skills as a groundbreaking scientist with a deep commitment to humanism, made him the compleat physician.

My role in helping define the anatomic bases for Schick’s various illnesses—he was 90 years old when he died—remains a strong and positive memory.

Béla’s father, Jacob, was a grain merchant in Graz, Austria. Jacob’s great love for France and its art led him to insist on being called Jacques rather than Jacob. Described as a good-humored and generous man, he was fond of philosophizing. Johanna Pichler Schick, Béla’s mother, was considered the most attractive woman in Graz, and one of the smartest.

In May 1877, Johanna Schick, well into the last trimester of her second pregnancy, accepted an invitation to visit her uncle, Dr. Sigismund Telegdy, at Bolgar, on the shore of Lake Balaton, Hungary. Béla Schick was born prematurely on July 16, 1877, weighing only a little more than three pounds. In a time when newborns as small as three pounds only rarely survived, the infant Béla had many complications.

Fortunately he was at the home of his grand-uncle, a skilled and creative physician, who provided constant attention and nursed the weak newborn back to health. It is said, perhaps apocryphally, that Uncle Sigismund told Johanna that the baby Béla, having survived despite great odds, had a special obligation to himself become a physician and pay back a debt to mankind. Béla visited his grand-uncle many times in his childhood, often discussing life, philosophy, and, particularly, medicine.

In 1938, on being honored on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of discovery of the Schick test, he restated his favorite passage from Louis Pasteur’s writings: “It is within the power of civilized man to cause the infectious diseases to disappear from the earth.” This was the motivation for Schick’s life’s work.

Schick graduated as a physician from the Karl Franz University in Graz, 1900, following which he served an obligatory six-month period of army service. An accomplished musician and pianist, he produced a number of compositions that became part of the repertoire of the Austro-Hungarian army band.

At the University of Vienna he worked with the great Professor Theodor Escherich (whose name is immortalized in the name for the bacterium Escherichia coli; E. coli), a pioneering pediatrician and microbiologist. Clemens von Pirquet, three years Schick’s senior and also from Graz, was Escherich’s senior assistant. Von Pirquet and Schick became close friends and engaged in highly productive collaborative research that resulted in many important discoveries and included the publication, in 1905, of their historic work, Die Serumkrankeit (Serum Sickness). It is no exaggeration to note that the clinical discipline of allergy began with the publication of this book.

Von Pirquet and Schick proposed the then revolutionary concept that a second exposure to an antigen accentuates the allergic reaction, with both an immediate reaction at the site of the injection of the antigen and the subsequent accelerated development of a systemic illness because of preformed antibodies that developed following the initial injection. Von Pirquet was brilliant, restless, and impatient and moved from project to project as soon as possible. Schick, in contrast, was analytical, persistent, and tended to stick with a problem until he exhausted all attempts at a solution or explained all nuances of the scientific issue.

In the Saint Anna Hospital’s scarlet fever (a very common disorder in those years) pavilion, he gathered clinical material for his landmark study on the complications of scarlet fever (Die Nachkrankheiten des Scharlachs). He believed the late manifestations of scarlet fever were the result of a delayed allergic reaction.

In 1906, wanting new challenges, he transferred to the diphtheria pavilion.

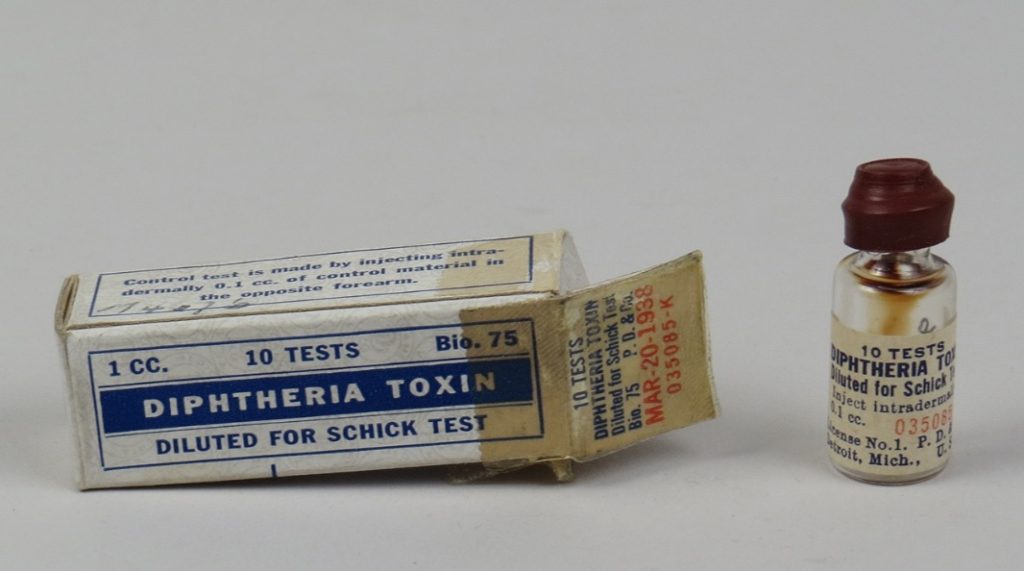

Schick’s most important and most enduring contribution was the development and implementation of what came to be known as the Schick test for diphtheria. Diphtheria had an exceedingly high mortality, particularly in children.

The discovery of the Schick test was not accidental. Schick had been one of the first to use the skin reaction to the purified protein derivative of the tuberculosis organism (“tuberculin”)—developed by von Pirquet in 1895 and refined by Mantoux in 1907—to demonstrate prior exposure to tuberculosis. Schick was determined to develop something similar for diphtheria.

Diphtheria is a horrible disease. In its worst form, children develop signs and symptoms two to seven days after infection. High fever, chills, easy fatigability, headache and hoarseness are common as the causative bacterial organism, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, and the reaction to it, leads to the destruction of healthy tissue in the respiratory tract. Typically, a thick, gray inflammatory  “pseudomembrane” covers the mucus membranes of the nose, tonsils, pharynx and larynx, including the vocal cords. Patients then have difficulty breathing, experience painful swallowing and, eventually, have low blood oxygen levels with cyanosis leading to what is, in effect, suffocation. There may be cardiac inflammation (myocarditis) with arrhythmias and heart failure. In some patients the nervous system can be affected.

“pseudomembrane” covers the mucus membranes of the nose, tonsils, pharynx and larynx, including the vocal cords. Patients then have difficulty breathing, experience painful swallowing and, eventually, have low blood oxygen levels with cyanosis leading to what is, in effect, suffocation. There may be cardiac inflammation (myocarditis) with arrhythmias and heart failure. In some patients the nervous system can be affected.

Schick described the test: “By the injection of a minute quantity of diphtheria toxin into the skin, it can be determined whether or not an individual is susceptible to diphtheria. No reaction at the place of injection means immunity against the disease. This is called a negative reaction and proves the presence of those substances in the organism which neutralize the diphtheria toxin. In cases where there is a lack of such substances a distinct redness appears at the place where the test was made, and this is called a positive reaction. The latter means susceptibility to diphtheria.”

diphtheria toxin into the skin, it can be determined whether or not an individual is susceptible to diphtheria. No reaction at the place of injection means immunity against the disease. This is called a negative reaction and proves the presence of those substances in the organism which neutralize the diphtheria toxin. In cases where there is a lack of such substances a distinct redness appears at the place where the test was made, and this is called a positive reaction. The latter means susceptibility to diphtheria.”

Vast numbers of children throughout the world have been tested with this easy to apply technique in campaigns to eradicate diphtheria. Fortunately, routine vaccination for diphtheria is safe and completely effective and diphtheria is now exceedingly rare in the United States.

In 1908, von Pirquet left Vienna to become chairman of the Department of Pediatrics at the relatively new Johns Hopkins Medical School in Baltimore. Ten years later, Schick was appointed “Extraordinary Professor of Children’s Diseases” at the University of Vienna. This unique title was developed because only Catholics could become full professors in the Germany and Austria of those years and the euphemism “extraordinary” was used to designate the lower rank of the unbaptized.

Schick immigrated to New York two decades later to become Director of the Department of Pediatrics at The Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

Schick’s decision to leave Austria, where more than 30 members of his immediate family would eventually die in the Holocaust, was, of course, fortunate for him and also fortunate for the development of pediatrics. During the 1930’s he made many trips to Europe and was keenly aware of the growing menace of Nazi Germany. Schick himself sponsored scores of people for admission to the United States before and during the years of World War II. His wife, Catherine, worked tirelessly to arrange lectures, banquets and dinners, and exhibitions and programs for the benefit of the victims of Nazism. During those years Schick’s typical day included visits to three hospitals, private consultations, and a variety of welfare and social obligations which consisted mostly of helping Austrian and German intellectuals of Jewish ancestry settle in the United States.

The occupation of Austria destroyed all of his illusions when he learned of the destruction, murder, and suicide of so many physicians he had counted as friends. In 1938 he and his wife were in Italy, a country he very much loved. They were ejected from their hotel to make room for a company of German Nazis who would not stay under the same roof with a Jew.

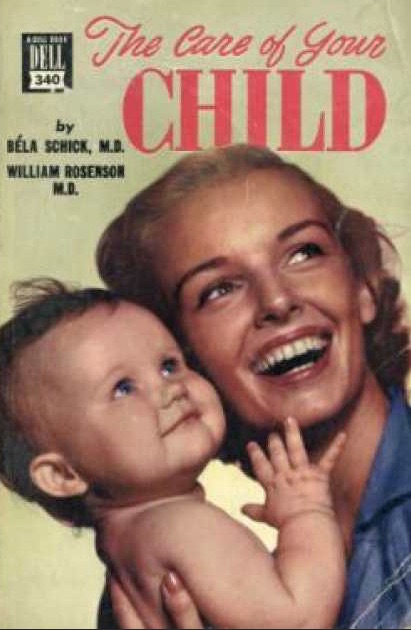

Schick created one of the great departments of pediatrics at Mount Sinai. A generation of students who studied with him became leaders in both pediatrics and pediatric allergy. In 1932 Schick and William Rosenson wrote a book for the lay public, The Care of Your Child.

Although comprehensive, it was written in simple terms and served as a useful guide for the care of both healthy and sick infants and children. In fact, it was the most useful and popular guide for young parents until Benjamin Spock’s Baby and Child Care was published in 1946

for the care of both healthy and sick infants and children. In fact, it was the most useful and popular guide for young parents until Benjamin Spock’s Baby and Child Care was published in 1946

In 1942 Schick reached Mount Sinai’s then mandatory age of retirement, 65. However, he continued to be an active practicing pediatrician and, in 1950, was appointed pediatrician-in-chief at Beth-El Hospital, in Brooklyn. This was not, in any way, an honorary position and carried full administrative and clinical

responsibilities along with the title. He commented about slowing down in the practice of medicine: “It is very difficult to slow down. The practice of medicine is like heart muscle contraction. It is all or none.” In 1955 he became visiting professor of pediatrics at the new Albert Einstein College of Medicine; the pediatrics department was named in his honor.

responsibilities along with the title. He commented about slowing down in the practice of medicine: “It is very difficult to slow down. The practice of medicine is like heart muscle contraction. It is all or none.” In 1955 he became visiting professor of pediatrics at the new Albert Einstein College of Medicine; the pediatrics department was named in his honor.

For most of his life, he was in excellent health. In later years he had Parkinson’s disease but was still quite active. In November 1967, while travelling in Brazil, he developed cardiac and renal failure. Flown from Rio de Janeiro to Mount Sinai he died at the age of 90, on December 6, 1966.

One of his former students wrote: “those of us fortunate to have served under him … learned a great deal about medicine – but we learned more about the human heart. The heart of Béla Shick is warm, humble, gracious and simple. It has never lost touch with the simple truths of life, the innocent beauty and love of a child, the therapy of a smile.” He had a wonderful sense of humor and it was characteristic that his jokes were always kindly without the slightest barb. He was awarded dozens of medals, prizes, scrolls, and other tangible records of the world’s regard, yet remained a completely modest man.

Schick’s personal qualities led to numerous delightful and meaningful teachings. I.I. Wolf, Schick’s student and colleague, collected many of them in Aphorisms and Facetiae of Béla Schick. Schick believed strongly in “the therapy of a smile.” Before examining a child he always played with him or her first. Sometimes he would crouch on the floor pretending to be a bunny: “You have to be a little childish yourself to be a good pediatrician,” he said. One of his best-known concepts, in a time when there were far fewer therapeutic choices than now, was that the physician’s best remedy often was “tincture of time.” This rule, suggesting patients often improve with watching and waiting, is often valid today.

Schick also recognized how rapidly changes occur in the world of medicine and how short human memory could be. He suggested every chief of service have a pet dog to be left behind when retiring from the department in which he served since, “when you return the only one who will remember you will be your dog.”

References

Birch CA. The Schick test. Béla Schick (1877-1967). Practitioner 1973: 210: 843-844.

Cone TE Jr. Béla Schick, 1877-1967, a gracious man. Pediatrics 1968; 24: 1013.

Glaser J. Pediatric allergy as a specialty. Annals of Allergy 1972; 30: 1-10.

Gribetz D. Pediatrics at Mount Sinai. Mount Sinai Journal of Med 1997; 64: 392-398.

Gronowicz A. Béla Schick and the World of Children. New York, Abelard-Schuman, 1964.

Hodes HL. Béla Schick, 1877-1967. Pediatrics 1968; 41: 379-381.

Karelitz S. Béla Schick 1877-1967. Journal of The Mount Sinai Hospital 1968; 35: 211-213.

McGovern JP. On the two cultures in medicine as reflected by the holism of Béla Schick. Annals of Allergy 1970; 28: 341-347.

Pelner L. Béla Schick, M.D. (1877-1967). New York State Journal of Medicine 1972; 93: 1067-1070.

Peshkin MM. Béla Schick: scientist, humanitarian, friend. Annals of Allergy 1968; 26: 625-636.

Wolf IJ. Aphorisms and facetiae of Béla Schick. Baltimore, Waverly Press, 1965.

Wolf IJ. Béla Schick. Journal of the American Medical Association 1968; 203:98.

December 10, 2019 at 8:38 pm

Favorite medical student exam question: A child presents with sore throat, rash, and heart block. What is the diagnosis?

Answer: Diphtheria with diphtheretic myocarditis.

December 11, 2019 at 9:56 am

Dr. Geller, thank you very much for sharing this essay and important aspect of the history of Medicine. I am also amazed at all the important physicians who have at one point worked at Mount Sinai Hospital.

December 11, 2019 at 2:16 pm

This is a beautifully written contribution to the history of medicine. It is also a timely reminder of the power of vaccines and how quickly we forget about the diseases they prevent.

I have read and thoroughly enjoyed “A Little Piece of Me,” but I am not aware of another novel you have written. What is it called? I look forward to your still-in-progress third novel.

Early during my first year of residency, I did an autopsy at the VA Hospital in the Bronx on a veteran who had been found in horrific shape on the streets and brought into the hospital. He died the next day, before the residents had had a chance to work him up. His death was thought to be due to metastatic cancer. The physicians had hoped to remove a hard tumor mass protruding like an appendage from his hip that they figured would inform them of the cancer type, but they didn’t have a chance to do so before he died. As I started the autopsy, Dr. Choi did a frozen section on the mass. She excitedly returned to tell me that it was a Calcifying Epithelioma of Malherbe (pilomatrixoma). I had never heard of it, and she reviewed the slides with me after I finished the autopsy.

The residents were right in that the patient did, in fact, die of metastatic cancer. He had metastatic renal cancer. But, of course, a biopsy of the mass would not have helped make the diagnosis.

Apparently, without his fondness for quotes, Béla Schick never would have studied medicine. It says on Wikipedia that a “young Bela Schick quoted the Talmud: ‘The world is kept alive by the breath of children,’ to help persuade his father to allow him to pursue continued education in pediatrics, rather than to join the family grain merchant business in Graz, Austria.”

December 11, 2019 at 2:21 pm

Karen,

Thank you for this comment. I appreciate the additional information about Schick as well as hearing about your own encounter with the Malherbe lesion.

Best wishes and warmest regards.