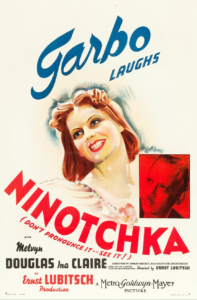

Every now and then the name of Greta Garbo is injected into a conversation (sometimes by me). It is always surprising, and even a little disappointing, to find many people, including some close to my age, who have never seen a Garbo movie. A few have only seen one Garbo movie, usually the charming and delightful Ninotchka, one of her last films. My next reaction, after surprise and disappointment, is sadness that people have not had the special pleasure of seeing the magnificent Garbo.

She was one of the most beautiful of women and one of the most wonderful actors (nominated three times for an Academy Award in a relatively short career). Others come to mind: Elizabeth Taylor, Marilyn Monroe, Ava Gardner, Vivian Leigh, Ingrid Bergman, Catherine Deneuve and more but, at least in my view, Garbo’s stunning looks outshone them all. Perhaps it was her large eyes, proclaiming deep intelligence when she was serious in a melancholy and somber role or, alternatively, teasing merriness when being comedic. It was decidedly the way her face expressed so much emotion that made her so special but there was much more.

I might be biased because of my brief encounter with her. Or, at least, her ankle. In July, 1964, I was an intern at Lenox Hill Hospital (LHH) on East 77th Street in Manhattan and, ever so briefly, Greta Garbo was my patient.

Lenox Hill Hospital has long been one of Manhattan’s leading hospitals. Founded in 1857 as the German Dispensary, it has occupied the present site, almost the entire block bounded by Lexington and Park Avenues and East 76th and 77thStreets, since 1869 when it was renamed the German Hospital. The name was changed to Lenox Hill Hospital after World War I when there was strong anti-German sentiment. Lenox Hill Hospital was, in the years I was there, considered the place where famous people were treated. Winston Churchill, Marilyn Monroe, Nelson Rockefeller and a host of politicians, musicians and artists got medical care there. It was, in fact and in story, the quintessential Park Avenue hospital. Lenox Hill Hospital is also the hospital of the New York Yankees baseball team, since the time of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, as well as the New York Jets football team (I also helped in the care of the great quarterback, Joe Namath, when he was hospitalized for one of his many knee surgeries and had a headache in the middle of the night, but that is a story for another blog). Notably, it has been the site of many medical milestones as well as the venue where several pioneers of American medicine practiced. Willy Meyer developed thoracic surgery at Lenox Hill at a time when his colleague Abraham Jacobi formed the specialty of pediatrics. In recent years it has become a renowned center for cardiac care and sports medicine.

I first came to Lenox Hill Hospital in 1955 in my last months as a senior at Stuyvesant High School when my classmate and good friend, Anthony Yiavasis, told me he was going to Lenox Hill to interview for a volunteer position. He suggested I go with him. Tony always wanted to be a physician and eventually became a surgeon. In those years I did not know what I wanted to be, although I had thoughts of being a writer. I was not thinking of medicine as a career and went along because it seemed like an interesting and worthwhile thing to do. Tony and I were accepted as volunteers. I don’t remember exactly what I did the two afternoons I went to Lenox Hill but, in June, upon graduation, I was offered, and accepted, a paying summer job.

I was assigned to the Neurology/Psychiatry Ward which was then housed in the oldest building, facing Park Avenue. That building is long gone, replaced in 1965-66 by a new, modern structure. The head nurse on Neuro/Psych was the gray-haired and bespectacled Rose Wabersich, a very kind person but, it seemed to me in my just-barely-16 wisdom, somewhat scatterbrained. Fortunately for me and the patients, her senior assistant was Patricia Torsiello, a young nurse with limitless energy and good humor who taught me how to carry out the multitude of tasks then thought to be a part of a nurse’s responsibility (e.g., making beds, cleaning bedpans,  giving backrubs, taking patients for x-rays and more). Patty taught “the right way,” not the “just okay” way. She was efficient and exceedingly well organized and, as I soon learned, the Neuro/Psych Ward was one of the best run units in the hospital. I learned organization skills, record-keeping, ‘clean’ (as opposed to ‘sterile’) technique as well as hospital hierarchy, rules and manners. In those days nurses and their assistants – including me! – stood when a physician came to the unit.

giving backrubs, taking patients for x-rays and more). Patty taught “the right way,” not the “just okay” way. She was efficient and exceedingly well organized and, as I soon learned, the Neuro/Psych Ward was one of the best run units in the hospital. I learned organization skills, record-keeping, ‘clean’ (as opposed to ‘sterile’) technique as well as hospital hierarchy, rules and manners. In those days nurses and their assistants – including me! – stood when a physician came to the unit.

Patty was my first (unexpressed and unrequited) ‘crush.’

There were two sections, one for men, where I was assigned, and one for women, separated by a partial wall with a wide passageway. At the far end of the men’s ward was a small room for electroconvulsive (“shock”) therapy (ECT) where I spent considerable time assisting the psychiatrists and nurses administering this form of treatment. In those days, effective muscle relaxants were not available and my role was to put my upper body weight across the patients’ legs as they had convulsions upon being shocked. Today, patients remain completely relaxed with pharmacological assistance.

Shock therapy went out of favor for many years but has been reintroduced. I can’t speak with great knowledge about shock therapy, either then or now, but I was always impressed at its effectiveness. It was my good fortune to begin my hospital days in a time when patients spent more time in hospitals and staff members, including me, had time to become acquainted with them. In 1955, patients were admitted the afternoon before ECT and discharged the day after. I consistently observed how shock therapy could help severely relatively non-communicative and sullen people become cheerful and friendly. The indications for ECT are more limited today than they were approximately 65 years ago but it is still used for patients with depression.

The year after my Neuro/Psych service I was invited to work in the operating rooms, which I did every summer until I was accepted to medical school. Those were among the best years of my life, serving as a counterbalance to my relatively unhappy college years and introducing me to marvelous people, surgeons and nurses, nursing assistants (then called ‘technicians’) and others (custodial staff, clerks, etc). I had wonderful experiences, that may be covered in a future blog. It is impossible to summarize the things I learned there, contributing immeasurably to my experiences as a medical student, intern and, ultimately, pathologist. My responsibilities encompassed whatever the O.R. nurses did, except give medications and engage in administrative activities. The two major activities for nurses in operating rooms are ‘scrubbing’ and ‘circulating.’ The scrub nurse directly assists the surgeon, preparing the sterile instruments for the procedure, helping the surgeon cover the patient with sterile drapes, and, during the surgery, passing the instruments, sutures, gauze sponges, cautery, and other materials the surgeon needs. It was here that I learned ‘sterile technique,’ something not generally taught well in medical schools. The circulating nurse does not wear a sterile gown or sterile gloves but, instead, assures that anything additional that is needed is available. As an example, the surgeon might request some other suture material than originally thought needed. Additional sponges might be required. The operating room lights might need adjusting.

I took call, sleeping in the hospital for any night surgery that was needed. I worked both circulating and scrub. During my last summer I was the principal scrub for all neurosurgery cases, assisting two renowned but temperamentally difficult neurosurgeons carrying out a variety of procedures on the brain and spinal cord. I never figured out if I was given that assignment because I was regarded as capable enough or because the other nurses didn’t want to work with those demanding surgeons.

The most important event of my years at Lenox Hill was that I met my wife, Kate, when I was working in the  operating rooms. She was a student nurse and I was immediately and irrevocably transfixed by her warm smile and her indomitable spirit. ‘Liberated’ before most of us heard of Betty Friedan or Gloria Steinem, a defender of the climate and practitioner of recycling before almost anyone, a terrific tennis player, an excellent cook and baker, a gracious and welcoming hostess, and much more, there have not been many dull moments in our more than 60 years together.

operating rooms. She was a student nurse and I was immediately and irrevocably transfixed by her warm smile and her indomitable spirit. ‘Liberated’ before most of us heard of Betty Friedan or Gloria Steinem, a defender of the climate and practitioner of recycling before almost anyone, a terrific tennis player, an excellent cook and baker, a gracious and welcoming hostess, and much more, there have not been many dull moments in our more than 60 years together.

When I graduated from medical school, I returned to Lenox Hill for an internship. Most of the hospitals in New York had already transitioned to specialty-based internships by the time I was graduating. As a senior medical student, I knew I was planning to be a pathologist and I wanted more experience in the major medical disciplines to practice the many things I learned in medical school. Lenox Hill was one of the few remaining medical centers to still offer a ‘rotating’ internship.

Emergency was my first rotation as a bona fide physician, beginning July 1, 1964, one month after graduation from medical school. Two interns rotated in the emergency room at Lenox Hill in those days and we were each on duty 24 hours and off duty 24 hours. Today that would be considered an inappropriately strenuous assignment schedule so schedules of that kind are no longer permitted in American hospitals. In those days, we didn’t think very much about that. The schedules for the rest of my intern year would, today, also not be permitted. We worked 36 hours on and 12 hours off, rotating for three months each on surgery, medicine and obstetrics-gynecology and two months in pediatrics, for salaries that might appropriately be termed “chicken feed.” Sleep time was typically interrupted and, every now and then, you might work the whole night without any rest. It was only decades later that the ruling authorities decided this kind of schedule was both a form of exploitation and, especially, risky for patients to be cared for by exhausted physicians. When you are up all night and then working the following day you can feel like you are a zombie on autopilot but, almost always, at least for me, there was that mysterious ‘second wind’ bringing considerable energy and allowing me to continue. As I recall, I earned $2,700 that year. Rumor was that there was still one hospital in the United States that didn’t pay any salary to the interns. It was only in 1968-69, my last year as a resident, after threatened strikes in all the New York hospitals, that salaries were increased to almost livable amounts.

I have always, then and now, considered that internship one of the best years of my life. Learning day and night, challenged to use my knowledge every day, caring for people in need, guided by some of the best doctors I have ever known, I remain warmed by those memories. To top it off, my  photo was on the cover of the Lenox Hill Hospital annual report for 1964.

photo was on the cover of the Lenox Hill Hospital annual report for 1964.

There are many wonderful and inspiring, as well as funny, stories from the years I spent at Lenox Hill before I went to medical school as well as during the twelve months of internship but they will have to wait for some future blog.

As already noted, I returned to Lenox Hill for an internship. Most of the hospitals in New York had already transitioned to specialty-based internships by the time I was graduating. As a senior medical student, I knew I was planning to be a pathologist and I wanted more experience in the major medical disciplines to practice the many things I learned in medical school. Lenox Hill was one of the few remaining medical centers to still offer a ‘rotating’ internship.

In those days, unlike today, the LHH emergency room was on the East 76th side of the hospital and was a

relatively quiet, walk-in facility without an active ambulance service. We definitely took care of emergency situations, such as heart attacks, aspirations, strokes and other acute medical needs but there was little trauma, other than broken arms and legs. Car accidents, gunshot wounds, fire victims and similar problems did not come to Lenox Hill in those days.

It happened that my partner for the emergency room month also happened to be, in a sense, my birth mate: Dr. Marcel Sislowitz and I were born on the exact same day, April 26, 1939, he in Paris as his parents escaped the Holocaust and me, far less exotically, in Brooklyn. Our only interactions were at seven in the morning when we changed shifts.

Which brings us back to Garbo.

One early evening when I was on duty, a middle-aged woman limped into the emergency room and offered her painful ankle for examination. After an x-ray to exclude a fracture, I determined she had a sprain and wrapped the distressed part in an Ace bandage to help her walk with much less discomfort. I think I recommended an ice pack and aspirin, but I don’t specially recall that. To my eternal regret, I never looked as carefully at her face as I did her ankle.

Leonard Lyons was a much read newspaper columnist writing for the New York Post (when the Post, founded by Alexander Hamilton, was a highly regarded, liberal leaning publication). Characterized as a ‘Broadway’ columnist he was highly regarded for his veracity, always getting his stories from the people themselves and not relying on anonymous sources.

The morning after I placed that Ace bandage, my day off, the Lyons Den, Leonard Lyons’ daily column reported that Greta Garbo had been treated for an ankle sprain at Lenox Hill Hospital (my mother was a regular reader and called to ask about it). The next day, the first thing I did upon arriving for duty was check the emergency logbook. There it was: I had treated ‘Mrs. Brown’ for an ankle sprain. I remember the event, I remembered examining and eventually wrapping the ankle and I remembered exchanging a few words with a very soft-spoken older woman with sunglasses and a slight accent but, no matter how hard I tried, I could not remember looking at her face.

that Greta Garbo had been treated for an ankle sprain at Lenox Hill Hospital (my mother was a regular reader and called to ask about it). The next day, the first thing I did upon arriving for duty was check the emergency logbook. There it was: I had treated ‘Mrs. Brown’ for an ankle sprain. I remember the event, I remembered examining and eventually wrapping the ankle and I remembered exchanging a few words with a very soft-spoken older woman with sunglasses and a slight accent but, no matter how hard I tried, I could not remember looking at her face.

Internship is a time of intense learning. One of the things I learned from my encounter with ‘Mrs. Brown’ was to be sure to make eye contact, and engage in conversation, with patients.

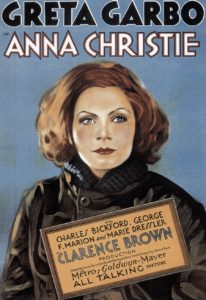

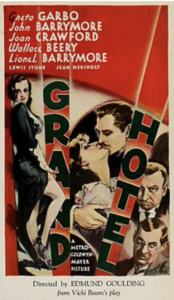

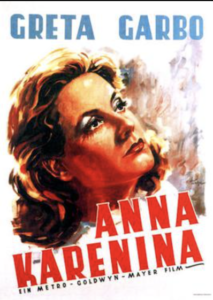

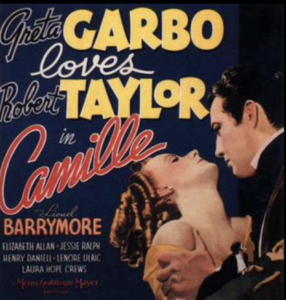

Greta Garbo was born in Stockholm, Sweden on September 18, 1905 as Greta Lovisa Gustafsson. Her  appearance in a 1924 Swedish silent film caught the attention of Louis B. Mayer, who was head of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios. She appeared in a number of silent films in America, gaining international renown in Flesh and the Devil, her third film. In 1930, after a number of silent films which led to her being MGM’s highest box-office star, she appeared in her first sound film, Anna Christie (advertised as ‘Garbo speaks’) and Romance, and received her first Academy Award nomination. The next five years saw her in a number of highly successful movies, including Grand Hotel, Queen Christina and Anna Karenina, three films I never tire of seeing. Queen Christina is a particular favorite of mine. Her second Academy Award nomination was for her performance as the dying courtesan in Camille, considered by many to be her finest performance. For a few years, her career seemed to decline (in 1938, she was considered by the Independent Theater Owners of American to be ‘box-office poison’ along with Joan Crawford and Katherine Hepburn) until she turned to comedy in the 1939 Ninotchka, another favorite (advertised as ‘Garbo laughs’) which earned her a third Academy Award nomination. She retired from the screen at the age of 35 after acting in 28 films, and became, in effect, a recluse. In 1954, an Honorary Academy Award was bestowed on her for “luminous and unforgettable screen performances.” She was revered by directors and other actors, including Bette Davis, Dolores del Rio and Gregory Peck who said she was his favorite actress of all time. Peck felt she was one of the earliest practitioners of ‘the method’ in her acting. One of her fellow actors in Camille, Rex O’Malley, said, “She doesn’t act, she lives her roles.” She was called the “Sarah Bernhardt of films.”

appearance in a 1924 Swedish silent film caught the attention of Louis B. Mayer, who was head of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios. She appeared in a number of silent films in America, gaining international renown in Flesh and the Devil, her third film. In 1930, after a number of silent films which led to her being MGM’s highest box-office star, she appeared in her first sound film, Anna Christie (advertised as ‘Garbo speaks’) and Romance, and received her first Academy Award nomination. The next five years saw her in a number of highly successful movies, including Grand Hotel, Queen Christina and Anna Karenina, three films I never tire of seeing. Queen Christina is a particular favorite of mine. Her second Academy Award nomination was for her performance as the dying courtesan in Camille, considered by many to be her finest performance. For a few years, her career seemed to decline (in 1938, she was considered by the Independent Theater Owners of American to be ‘box-office poison’ along with Joan Crawford and Katherine Hepburn) until she turned to comedy in the 1939 Ninotchka, another favorite (advertised as ‘Garbo laughs’) which earned her a third Academy Award nomination. She retired from the screen at the age of 35 after acting in 28 films, and became, in effect, a recluse. In 1954, an Honorary Academy Award was bestowed on her for “luminous and unforgettable screen performances.” She was revered by directors and other actors, including Bette Davis, Dolores del Rio and Gregory Peck who said she was his favorite actress of all time. Peck felt she was one of the earliest practitioners of ‘the method’ in her acting. One of her fellow actors in Camille, Rex O’Malley, said, “She doesn’t act, she lives her roles.” She was called the “Sarah Bernhardt of films.”

She was once designated “the most beautiful woman who ever lived” by the Guinness Book of World Records and, in 1950, the “best actress of the half-century” in a Daily Variety opinion poll. She earned many other awards, including appearing on American and Swedish postage stamps and, in 2014, the 100-krona banknote. More about her fascinating life is in Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greta_Garbo) as well as in many books and magazine articles. In 2005, Turner Classic Movie channel (TCM) produced a documentary, Garbo, narrated by Julie Christie.

She was once designated “the most beautiful woman who ever lived” by the Guinness Book of World Records and, in 1950, the “best actress of the half-century” in a Daily Variety opinion poll. She earned many other awards, including appearing on American and Swedish postage stamps and, in 2014, the 100-krona banknote. More about her fascinating life is in Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greta_Garbo) as well as in many books and magazine articles. In 2005, Turner Classic Movie channel (TCM) produced a documentary, Garbo, narrated by Julie Christie.

You’ve never seen a Garbo film? What do I recommend?

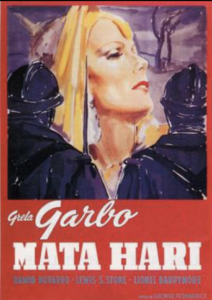

Anna Christie, Mata Hari, Grand Hotel, Queen Christina, The Painted Veil, Anna Karenina, Camille, Ninotchka.

Anna Christie, a 1930 film, and her first “talkie,” based on a Eugene O’Neill play, tells the story of Anna (“Christie”) Christofferson, the estranged daughter of Chris Christofferson, the skipper of a New York coal barge. After being raised for 15 years by relatives in Minnesota, she comes to live with her father. Emotionally traumatized during those 15 years, she worked in a brothel (this was the first of nine films Garbo made before the enactment of the highly

Anna Christie, a 1930 film, and her first “talkie,” based on a Eugene O’Neill play, tells the story of Anna (“Christie”) Christofferson, the estranged daughter of Chris Christofferson, the skipper of a New York coal barge. After being raised for 15 years by relatives in Minnesota, she comes to live with her father. Emotionally traumatized during those 15 years, she worked in a brothel (this was the first of nine films Garbo made before the enactment of the highly  restrictive Hays Code, censorship guidelines that limited portrayals of anything morally “corrosive”). In New York, she falls in love with a rescued seaman and eventually reveals her past. The film was a great critical and financial success and critics noted Garbo’s deep and sensual voice. Her famous first line is: “Gimme a whiskey, ginger ale on the side, and don’t be stingy, baby!”

restrictive Hays Code, censorship guidelines that limited portrayals of anything morally “corrosive”). In New York, she falls in love with a rescued seaman and eventually reveals her past. The film was a great critical and financial success and critics noted Garbo’s deep and sensual voice. Her famous first line is: “Gimme a whiskey, ginger ale on the side, and don’t be stingy, baby!”

Mata Hari is loosely based on the life of Margaretha Geertuida Zella, known as Mata Hari,  a celebrated Dutch courtesan, entertainer and dancer, and spy, who was executed for espionage during the first World War.

a celebrated Dutch courtesan, entertainer and dancer, and spy, who was executed for espionage during the first World War.

This was Garbo’s most successful film. The great silent films actor, Ramon Navarro, co-starred. When it was reissued, some years later,during the Hays Code era, many scenes, especially those with nudity or sex, were erased.

Grand Hotel, a glorious, star-filled (Garbo, John Barrymore, Joan Crawford, Wallace Beery, Lionel Barrymore, Lewis Stone, Jean Hersholt) 1932 film was selected, in 2007, for preservation by the Library of Congress for being “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.” It tells the complex stories of a series of guests at

Berlin’s Grand Hotel whose lives eventually interact.  Grand Hotel includes Garbo, as an aging Russian ballerina, delivering the oft-parodied lines: “I want to be alone. I just want to be alone.” These lines became legendary as representative of

Grand Hotel includes Garbo, as an aging Russian ballerina, delivering the oft-parodied lines: “I want to be alone. I just want to be alone.” These lines became legendary as representative of

Garbo’s personal, reclusive life although she later insisted, “I never said I want to be alone; I only said, ‘I want to be let alone.’ There is all the difference.”

Queen Christina tells a story based on the life of Christina of Sweden who, in 1632, became monarch at the age of six and grew to be a particularly strong and influential leader. In the  film, she is depicted as a young woman so devoted to governing and education that she has avoided romance and marriage. Her courtiers encourage her to marry a heroic cousin, Karl Gustave, but she spurns the recommendation. In order to temporarily escape royal restrictions and unwanted matchmaking, she escapes from the castle dressed as a man. She manages to obtain the last room at an inn. The innkeeper, unaware of her identity as well as her gender, convinces her to share the room with a lone traveler, Antonio, a Spanish envoy on the way to the capital. Antonia is played by John Gilbert with whom Garbo lived for some months. In their room, she eventually reveals to Antonio that she is a woman, but not that she is the Queen, and they spend the night and, because of a heavy snowfall, the next few days together. When they part, Christina assures Antonio they will meet again in Stockholm. The rest of the movie is marvelously complex and I will not spoil it by revealing more. A warm, witty, wonderful and beautiful movie. In 2020, the critic Leonard Maltin gave it 4 of 4 stars and called it: “Probably Garbo’s best film, with a haunting performance by Garbo …” whose love scenes with Gilbert “… are truly memorable, as is the famous final shot …”

film, she is depicted as a young woman so devoted to governing and education that she has avoided romance and marriage. Her courtiers encourage her to marry a heroic cousin, Karl Gustave, but she spurns the recommendation. In order to temporarily escape royal restrictions and unwanted matchmaking, she escapes from the castle dressed as a man. She manages to obtain the last room at an inn. The innkeeper, unaware of her identity as well as her gender, convinces her to share the room with a lone traveler, Antonio, a Spanish envoy on the way to the capital. Antonia is played by John Gilbert with whom Garbo lived for some months. In their room, she eventually reveals to Antonio that she is a woman, but not that she is the Queen, and they spend the night and, because of a heavy snowfall, the next few days together. When they part, Christina assures Antonio they will meet again in Stockholm. The rest of the movie is marvelously complex and I will not spoil it by revealing more. A warm, witty, wonderful and beautiful movie. In 2020, the critic Leonard Maltin gave it 4 of 4 stars and called it: “Probably Garbo’s best film, with a haunting performance by Garbo …” whose love scenes with Gilbert “… are truly memorable, as is the famous final shot …”

Garbo’s last pre-Code film, The Painted Veil, is based on the W. Somerset Maugham novel of marital infidelity. It doesn’t follow the original as closely as the fourth film version, starring Naomi Watts, Edward Norton and Liev Schreiber, but Garbo’s performance is outstanding.

Garbo’s last pre-Code film, The Painted Veil, is based on the W. Somerset Maugham novel of marital infidelity. It doesn’t follow the original as closely as the fourth film version, starring Naomi Watts, Edward Norton and Liev Schreiber, but Garbo’s performance is outstanding.

Anna Karenina was after the Code was instituted and also focuses on infidelity but, perhaps because it is an adaption of one of the greatest novels ever written,

Leo Tolstoy’s, it was allowed to proceed. Garbo received the New York Film Critics Circle Award for her performance. The great writer—Graham Greene—said: “… it is Greta Garbo’s personality which ‘makes’ this film, which fills the mould of the neat respectful adaptation with some kind of sense of the greatness of the novel.” The film has been acclaimed by many modern critics.

Based on the 1848 novel and 1852 stage production, La Dame aux Camélias (The Lady of the Camelias), by  Alexandre Dumas, Camille is the epitome of romanticism. In today’s world it might flippantly be termed a ‘four-hanky’ production.

Alexandre Dumas, Camille is the epitome of romanticism. In today’s world it might flippantly be termed a ‘four-hanky’ production.

Garbo is Marguerite Gautier, a well-know courtesan in mid-19thcentury Paris, who has a chronic respiratory disease (not named in the movie but clearly tuberculosis or, as it was often called, ‘consumption’). Mistaken identity leads to romance with the relatively poor Armand Duval (the almost impossibly handsome Robert Taylor) instead of the wealthy Baron de Varville, who she was supposed to meet. A beautiful script and a beautiful production with beautiful actors. Critics praised it as Garbo’s finest performance and she received another Academy Award nomination for Best Actress.

Ninotchka, advertised as “Garbo Laughs,” earned Garbo her third and final Academy Award nomination for Best Actress. It is hard for me to pick a favorite Garbo film but this is certainly one of my top three. Ninotchka, wasreleased in 1939. (This was the best year ever for movies with Gone with the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Stagecoach, Goodbye Mr. Chips, Of Mice and Men, Wuthering Heights, Dark Victory, Love Affair and Ninotchka all nominated for Best Picture Academy Award.

Ninotchka, advertised as “Garbo Laughs,” earned Garbo her third and final Academy Award nomination for Best Actress. It is hard for me to pick a favorite Garbo film but this is certainly one of my top three. Ninotchka, wasreleased in 1939. (This was the best year ever for movies with Gone with the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Stagecoach, Goodbye Mr. Chips, Of Mice and Men, Wuthering Heights, Dark Victory, Love Affair and Ninotchka all nominated for Best Picture Academy Award.

Ninotchka is a romantic comedy and one of the first films depicting the rigidness of the Soviet Union under Josef Stalin. Three Soviet agents are in Paris to sell jewelry confiscated from the aristocracy during the Russian Revolution. Included are the court jewels once belonging to former Russian Grand Duchess Swana, whose paramour, Melvyn Douglas as Count Leon d’Algout, offers to help her  retrieve her valuables. Leon interferes with the sale and sends a telegram to Moscow suggesting a compromise deal. Angered, Moscow sends Nina Ivanovna (“Ninotchka”) Yakushova, played by Garbo, to return home with the jewels and the three renegade agents. Methodical, rigid, and stern until she and Leon meet, this is the most delightful of Garbo’s performances and one of the most charming and delicious films of all time.

retrieve her valuables. Leon interferes with the sale and sends a telegram to Moscow suggesting a compromise deal. Angered, Moscow sends Nina Ivanovna (“Ninotchka”) Yakushova, played by Garbo, to return home with the jewels and the three renegade agents. Methodical, rigid, and stern until she and Leon meet, this is the most delightful of Garbo’s performances and one of the most charming and delicious films of all time.

Garbo retired from acting when she 35, after performing in only 28 films, 22 of them in America. She never married and never had children. She lived alone for most of her life. When she was younger, she had well-publicized affairs with her fellow actor, John Gilbert, the orchestra conductor, Leopold Stokowski, and others, including a number of women. In her last years, she had breast cancer and renal failure and died, in 1990, at the age of 84.

You only have time for three films?

Grand Hotel, Queen Christina, Ninotchka.

You only have time for one?

Puh-leeze …

July 9, 2022 at 3:07 pm

One of your very best blogs—a captivating combination of the personal and the critical.

July 9, 2022 at 4:11 pm

Thank you, David. Much appreciated! Best wishes and warm regards.

July 9, 2022 at 3:15 pm

Stephen neglects to tell us that during his internship he was chosen to be the “face” of the hospital, in that a photo of him with a patient was on the cover of a Lexox Hill publication (probably their “Annual Report.”)

July 9, 2022 at 4:10 pm

Somehow those few sentences and image got lost, but they are in there now.

July 9, 2022 at 3:36 pm

Loved this professional bio of a man that I always admired. Very well written. Sorry to say that I am one of those who may never appreciate Garbo. I am not sure that I have seen any of her movies. I will definitely make time to do so now. Thanks Steve!

July 9, 2022 at 4:13 pm

Joe, Glad you enjoyed this. You might also enjoy some of the prior blogs. You will definitely enjoy Garbo movies!

Best wishes.

July 9, 2022 at 4:12 pm

Wow my OLD friend. Your Mom kept my sister abreast about you, sorry the weekends I spent down with Tootie I never got to spend some time with your Mom. You truly have had some life for a kid that grew up on 16th street.

July 9, 2022 at 4:39 pm

Great piece, revealing great talent. Weaving words into marvelous stories is a special gift.

Wealth of experiences are a great platform for writing material. Keep going.

July 9, 2022 at 5:00 pm

Though I have long forgotten all the details, I once saw Garbo play the same part in both the English and German (in which she was fluent) versions of a film that was released in both languages. I was very impressed by her acting skills and how in the second shooting, she appeared and acted in identical fashion with only the language changed. Actually, I believe that she made both versions at the same time, just changing her language and working with another set of actors!

July 9, 2022 at 5:01 pm

Stephen, a pleasure to read.

July 10, 2022 at 9:33 am

Never realized you were THE guy who saved Garbo. Great story telling and I loved how you transitioned from G G to your H S days to your professional medical days. I also never knew that Kate was a nurse and original hippie. Great story and glad to have known you all these years. Be well

July 10, 2022 at 4:29 pm

Great master. An enriching and enjoyable read. Thanks for the opportunity