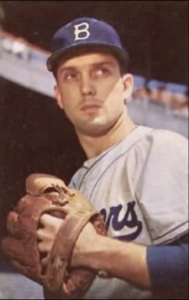

Two days ago, April 16, 2024, Carl Erskine died at the age of 97.

“Oisk” or “The Oisk,” as he was popularly named, was the last of the great Brooklyn Dodgers team of the 1950s, and one of the greatest baseball pitchers ever. The New York Times obituary “Carl Erskine, 97, the Last of the Dodgers’ ‘Boys of Summer,’” (https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/16/obituaries/carl-erskine-dead.html) alludes to one of the best sports books written.

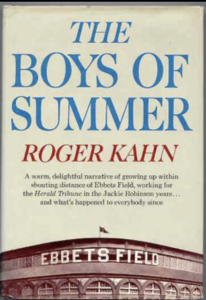

Roger Kahn’s’ The Boys of Summer was published in 1971, 14 years after the Brooklyn Dodgers ceased to exist, ostensibly—but not really—replaced by some similarly garbed pretenders in Chavez Ravine, Los Angeles. In my 39 years living in Los Angeles, I never went to Dodger Stadium and never saw the Los Angeles baseball team wearing the name ‘Dodgers’ on their uniforms play, but more about that later.

The Boys of Summer was a critical and commercial success, although some reviewers considered it be overly sentimental.

In 2002, Sports Illustrated magazine placed it among the “top 100 sports books of all time.” As of 2015, the book is cited as having sold approximately 3 million copies. A documentary based on the book was produced in 1983, narrated by the legendary entertainer Sid Caesar.

If you haven’t read this loving book, you should try it even if you are not a sports fan since it’s not really about sports or even about baseball. It is about the lives of young men whose athletic skills allowed them to successfully compete in the “national pastime” at a time when baseball was the most listened to and then most watched sport in America. It is particularly about the Brooklyn Dodgers players of the 1940s and 1950s, a time when New York City had three major league baseball teams—the New York Giants, the New York Yankees and, in the view of at least one entirely biased fan, the best of them all, the Brooklyn Dodgers. As others have also recounted, one rarely heard one kid ask another if they were Catholic or Protestant or Jewish. The question at that time was “You a Yank? A Giant? A Dodger?”

(L to R) The Boys of Summer: PeeWee Reese, Carl furillo, Jackie Robinson, Erskine, Gil Hodges, Don Newcombe, Duke Snider, Roy Campanella

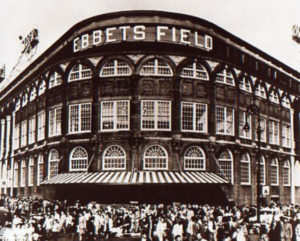

Visiting Ebbets Field to see a Dodger game, as I often did, was a memorable experience, whether they won or lost. It was a place of garishly colored advertising signs, periodically deafening sounds, and a cacophony of sweet smells, including roasted peanuts, popcorn, beer and hot dogs, as well

as a stadium overflowing with love and passion, triumph and, alas and too often, defeat. There was the frequently off-key Sym-Phony with its tuba, snare drum, beat-up old trombone and trumpet. Every now and then someone would hit the Abe Stark sign and earn a suit from that haberdasher, but never when I was there. There was the thrill of seeing some of the greatest players the game has ever seen with Brooklyn fans—being Brooklyn fans—cheering so many opposing players such as Stan Musial, Robin Roberts, Willie Mays and others, but never with the gusto and pride and love they showed for the home team. I never heard of the Dodgers being treated with as much respect when they visited other teams.

The book engagingly recounts needed information about the “boys of summer” in their youth but, especially, is about their years after their athletic careers were over.

The Dodgers were, for many years, known for their inadvertently comic activities and were often referred to as the “Brooklyn Bums.”. Once they had three men on one base. More than once two outfielders let a ball drop between them because they each thought the other would catch it. They were perennially the almost team, often winning the National League pennant but never winning the World Series and the team’s popular sobriquet “Dem Bums’ was too often accompanied by the annual October chant: “Wait ‘til next year.”

Until 1955.

I was in German class at Brooklyn College for the last few innings of the final game of the 1955 World Series, along with about 30 other silently groaning students. Frau Professor Zollinger was unsuccessfully competing with the other nine or ten thousand students who completely covered the quadrangle, all tuned to the same radio station on their transistor radios. Those thousands of radios, all roaring in unison with every successful catch or hit or when PeeWee Reese or Jackie Robinson or Duke Snider came to the plate. Eventually, Frau Professor Zollinger dismissed the class and we were able to join the masses listening to the last two innings with the Dodgers ahead. Johnny Podres, who had started the game, was pitching to Bill “Moose” Skowron, one of the Yankees’ heavy hitters who hit a ground ball right to Podres for the first out. A fly ball to Sandy Amoros in the left field was the second out. Elston Howard, another power hitter, was next up. After Howard hit to Reese for the third out, the roar seemingly loud enough to be heard anywhere in the world. The Dodgers finally won the World Series!

But this short essay is not about that game or any game. It is about one of those “boys of summer,” Carl Erskine, who was the last surviving member of that mythical and magical team and, in part, about a different era.

The Times obituary includes, as a sub-headline, “Pitching two no-hitters for Brooklyn’s storied group of the 1950s.” His first no-hitter was in 1952 against the Chicago Cubs and the second in 1956 against the New York Giants, both at Ebbets Field. I was lucky enough to be at both those historic events. Ebbets Field was a little more than two miles from our apartment on East 17th Street and Cortelyou Road and I often rode my bike to see a game, leaving it, unlocked, in a pile of other bikes.

Oisk was, on the surface, a country boy from Anderson, Indiana. He came from modest means. When he needed mastoid surgery (not uncommon before the era of antibiotics) his mother paid the surgeon’s bill by doing his wash for many years. As an outstanding high school pitcher, he attracted the attention of the Brooklyn Dodgers. When he graduated in 1945, and it was still unclear that World War II would soon end, he joined the United States Navy and was stationed at the Boston Navy Yard where, at the end of his tour of duty, the Boston Red Sox offered him a position. His heart, however, was with the Dodgers.

He stayed with the team for a season and a half when they moved to Los Angeles. Throughout his career he had a sore shoulder and finally retired from active play, serving as a pitching coach for a half year, enjoying the thrill of a second World Series win. He was offered an executive position with the athletic clothes division of Van Heusen, a large company, and was prepared to live in New York but his fourth child was born with Down syndrome. Determined to have little Jimmy have as full a life as he could, Erskine and his wife Betty, returned to Anderson. Jimmy competed in the Special Olympics and other competitions, often winning. Oisk devoted himself to various philanthropic and civic activities, in addition to being a commentator for ABC Sports. He and Betty were important advocates for human rights and civil rights. He was described, more than once, as an exemplary human being and “the best guy I’ve ever known.” He wrote two wonderful books, both of which I strongly recommend: Carl Erskine’s Tales from the Dodgers Dugout: Extra Innings, in 2004, and, in 2005, What I Learned from Jackie Robinson: A Teammate’s Reflections On and Off the Field.

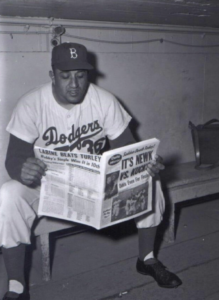

Writing about Erskine reminds me of many of those wonderful “boys of summer.” I especially worshiped Jackie Robinson, PeeWee Reese, Duke Snider and Gil Hodges (when Hodges, a devout Catholic, was hitless for a long time beginning at the end of the 1952 season including the entire World Series and the first weeks of the 1953 season, many Brooklyn churches, and even a few synagogues, held prayer sessions for him. Soon after, he started hitting again, leading Erskine, a Baptist, to say, “Gill, you just about made a believer out of me”). I was just as passionate about some of the pitchers, including Erskine, Billy Los and the great Don Newcombe.

Oisk started out as a relief pitcher from 1948 to 1950, until Newcombe (“Newk”), joined the team after which Erskine became a brilliant starting pitcher.

Don Newcombe was a magnificent pitcher, both as a starter and reliever. He never had great luck, however, in World Series games.

I met Newcombe a few times when he served as the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Director of Community Affairs. In that role, he often visited Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, to arrange special events that involved the team and the hospital. Once, I was heading for a meeting and saw him sitting in the lobby, where he was also waiting for a different meeting to start. I went over and re-introduced myself, trying not to gush too much over another of my heroes. We had a lovely conversation, mostly about his years in Brooklyn, the memory of which I still cherish. Checking my watch, I realized I was quite late for my meeting—he was still 15 minutes early—and I reluctantly started saying my goodbyes. He reached into his attaché case and pulled out two tickets for the double-header scheduled for the coming weekend. I put up my hand and said, “Thank you so much, Mr. Newcombe, but I’ve never been to Dodger Stadium and will never go there.” A gentle smile filled his face as he shook my hand and he said, “You know, there are a lot of folks out there like you.”

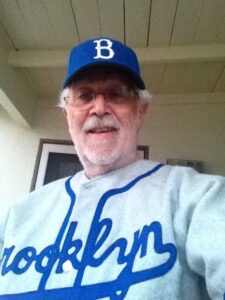

I met one of those “folks” in the lobby of a movie theater after the first

showing of the marvelous 2013 film about Jackie Robinson, “42.” I wore my Dodgers flannel shirt and Dodgers cap to the showing and bumped into someone dressed similarly when we left the movie theater at the same time. He had never been to Dodger Stadium either and swore he never would go there.

It’s dinner time. Perhaps I’ll have a little wine and make a toast to Oisk and all the other boys of those marvelous summers long since gone.

I think I’ll read that book again.

Note: And Then There Were None is the name of the bestselling crime novel of all time, written by Agatha Christie. She described it as the most difficult of her books to write.

April 18, 2024 at 1:09 pm

Hi Dr. Geller,

Thank you for sharing the story about Carl Erskine and your love of the Dodgers. I happened to be in Indianapolis this week for a conference and in between meetings I went to the Indiana State Museum on Monday- they had a prominently featured display of Carl Erskine’s jersey and he has a plaque in their Indiana Hall of Fame (along with David Letterman, Don Mattingly, Axel Rose, and others).

This last year, my kids have really gotten into baseball cards – I got each of them a card from the 1960s of Sandy Koufax for Hannukah and decided to treat myself to a 1955 Koufax rookie (in beat up condition but hey its his rookie card!) and was inspired to slowly start collecting the 1955 Topps card set. It features 18 Dodgers who played that year including: Jim Gilliam, Billy Herman, Johnny Podres, Don Hoak, Jackie Robinson, Jim Hughes, Sandy Amoros, Karl Spooner, Don Zimmer, Rube Walker, Bob Milliken, Joe Black, Clem Labine, Gil Hodges, Ed Roebuck, Bert Hamric, and Duke Snider.

Losing a twam is tough. When I was growing up in Houston we had the Houston Oilers who would find ways to lose in incredible fashion (we blew a 38-3 lead to the Bills in the Playoffs) but when they moved to Tennessee I had a hard time rooting for them – it was bittersweet seeing them lose in the Superbowl to the Cardinals in 2000 because I had rooted for the players but did not want the ownership to have the Superbowl win. Eventually Houston got the Texans and I have also rooted a bit for the Giants and Jets where I live now.

Did you ever adopt a new baseball team to root for? The Mets? My understanding is they took the colors of the Dodgers and Giants as an homage to them.

Amir

April 18, 2024 at 4:57 pm

Amir,

Thank you for the wonderful comments. I’m jealous of your visit to the Indiana Hall of Fame and also your cards collection. I had lots and lots of baseball cards when I was a kid (my grandfather owned a “candy store” and provided many) but I think they got lost when I went off to medical school. I did not adopt a new baseball team. My puny words can not appropriately express what it was to be a Dodger fan in those days. It was akin to being close to Olympian Gods. I once shook Jackie Robinson’s hand and refused to wash it when my mother called me to dinner.

By the way, I now live in New York again and do pay a little attention to the football teams but I am a big fan of Patrick Mahones and have sold my soul to Kansas City. The Mets have not inspired me and I still dislike the Yankees.

Hope all is well with you and your family.

Happy Passover and Best wishes.

Stephen