Classical music first became important to me when I was a student at Brooklyn College in the late 1950s, although I heard music, especially opera, which my grandfather loved, from childhood. My piano lessons, of course, included compositions by Bach and Chopin and others. As I noted in prior blog posts (Beethoven’s 250th; 50 years of celebration – December 16,2020 – https://stephenageller.com/2020/12/16/beethovens-250th-a-half-century-of-celebrations/, and Beethoven, the Conductor – October 1, 2022 – https://stephenageller.com/2022/10/01/beethoven-the-conductor/), I love the music of Beethoven more than that of any other composer. His life story is thrilling and inspirational. Beethoven’s 5th and 7th symphonies, pieces I have heard many times on the radio, on one of the vinyl or CD sets I have, as well as in person, stand high on my list of favorite compositions and would guess that I have heard them as many as 50 times each. They are often referred to as “war horses” reflecting that they are so often performed and are part of the repertoire of every orchestra in the world, along with Mozart’s 39th, Tchaikovsky’s 5th, Schubert’s 9th and many others.

The first time I heard Jaap van Zweden (yaap van svay-den) conduct was in 2017, in Los Angeles, before the pandemic began. The concert was a part of

our regular series of Los Angeles Philharmonic concerts and the program consisted of Beethoven’s 5th and 7th symphonies.

After that concert I commented to Kate, my wife, that I felt as if I had heard both symphonies for the first time. I don’t know enough about music or conducting to explain exactly how a conductor adds his or her interpretation to the 80 or more individuals who are being led and I sometimes, jokingly, ascribe a particularly memorable concert experience to some form of music magic.

Two weeks ago, on June 6, 2024, van Zweden, the 26th Music Director of the New York Philharmonic, in the last week of his tenure (more about that later), performed that magic again in conducting the Symphony #2 of Gustav Mahler, a composition commonly referred to as the “Resurrection” symphony. It was a glorious performance and one that I will never forget. As the New York Times noted in a recent review of that performance, van Zweden’s tenure as Music Director has only occasionally been marked by such revelatory concerts. In general, his performances, as a recent presentation of the Mozart Requiem Mass, have been disappointing for their lack of spark. Mahler’s 2nd is not one of the “war horses.” It is a piece that demands much of the orchestra, of the soloists and choir, as well a great deal from the audience, and is infrequently performed. The first time the Mahler 2nd was performed by the New York Philharmonic (then called the New York Symphony) was on Tuesday evening, December 8, 1908. The orchestra was led by its new conductor, Gustav Mahler himself. The New York Times praised the performance but described some aspects as “lacking in unity and proportion” and “fragmentary and bizarre.”

Mahler’s 2nd is not one of the “war horses.” It is a piece that demands much of the orchestra, of the soloists and choir, as well a great deal from the audience, and is infrequently performed. The first time the Mahler 2nd was performed by the New York Philharmonic (then called the New York Symphony) was on Tuesday evening, December 8, 1908. The orchestra was led by its new conductor, Gustav Mahler himself. The New York Times praised the performance but described some aspects as “lacking in unity and proportion” and “fragmentary and bizarre.”

Some of the most illustrious conductors in the history of music have led the New York Philharmonic, including Arturo Toscanini, who did not like Mahler’s music and rarely played it. In contrast, Leonard Bernstein

and Zubin Mehta have been strong Mahler proponents and Bernstein’s recording of the 2nd is especially thrilling and worth hearing.

Since that highly auspicious American premiere the 2nd has been played many times by the New York Philharmonic. In the wake of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Leonard Bernstein conducted it on a national broadcast. Bernstein also performed the 2nd with orchestras around the world, including a number of times with the Israel Philharmonic including in 1948, in the orchestra’s early days, and again in 1967, on Mount Scopus, at the end of the Six Day War.

On September 10, 2011, conductor Alan Gilbert, van Zweden’s predecessor, marked the tenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks with a performance. When Carnegie Hall reopened after a major renovation in December 1986, Zubin Mehta and the New York Philharmonic played the glorious 5th movement to celebrate the occasion. It’s no accident that Bradley Cooper’s thoughtful biopic about Bernstein, Maestro, highlights the finale of the 2nd with it’s climactic reenactment of Bernstein leading the London Philharmonic in 1973 in England’s Ely Cathedral. As majestic and magnificent as any music ever written.

This 2024 performance was programmed by Maestro van Zweden for his final subscription concert as Music Director. He is leaving New York to serve as Music Director of both the Seoul Philharmonic and, in 2026, the Orchestre Philharmonic de Radio France in Paris. Effective 2026, the New York Philharmonic will be led by Gustavo Dudamel who has been at the helm of the Los Angeles Philharmonic since 2009, a post he is leaving to be the 27th Music Director of the New York Philharmonic. As subscribers of the Los Angeles ensemble for almost 40 years, we were privileged to hear Dudamel, an extraordinary musician and conductor, and were thrilled when it was announced he was following us to the “big apple”

In contrast to Beethoven’s music, which I have loved for more than half a century, I only started listening to Mahler when I was in my mid-40s, first introduced to him at an L.A. Philharmonic concert when his Symphony #1 (named by Mahler as “Titan”) was performed.

I then heard the Gilbert Kaplan (1941-2016) recording of the 2nd with the London Philharmonic. Gilbert Kaplan was a publisher of an investment magazine, Institutional Investor, which he sold in 1984 for, according to the New York Times, approximately $75 million. He became obsessed with the

Mahler 2nd in his early 20s when he heard Leopold Stokowski conduct the piece with the American Symphony Orchestra. With no special musical education—he could hardly read music—he travelled the world to meet with some of the greatest conductors for the sole purpose of learning to conduct the 2nd. After years of study and memorizing the score, he hired the American Symphony Orchestra, soloists and the Westminster Symphonic Choir and rented Avery Fisher Hall (now David Geffen Hall) at New York’s Lincoln Center. Despite requests that no reviews be published, a reporter for The Village Voice wrote a review which was strongly positive. Subsequently, Kaplan, performed the piece with more than 100 orchestras throughout the world, never accepting a fee for his services. He twice recorded “the Resurrection symphony” with the London Symphony Orchestra and once with the Vienna Philharmonic. The New York Times obituary described him as an “improbable conductor.”

Another “improbable conductor” I knew was the pathologist William Siegel of Los Gatos, California. Bill was an outstanding pathologist who served as President of the California Society of Pathologists. After serving as a flight surgeon in the United States Navy, he continued to fly, once piloting an airplane from London to Sydney, Australia. He captained a sailing vessel to Tahiti (see the previous blog—Wanderer—about Sterling Hayden) and motorcycled from Cairo to Johannesburg. He was a kind, soft-spoken, highly cultured man

His obsession, however, was Verdi’s La Traviata. Also not a musician, he studied for years with the San Jose Opera Company, “world-class” opera company sometimes considered a steppingstone to New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Bill celebrated his 70th birthday by renting the hall, the orchestra and the singers, and invited friends to attend the performance to benefit the Opera Company. It was a wonderful Traviata. He was a remarkable human being.

I became a devoted Mahlerian soon after hearing that Kaplan recording and learning about the man and his music. I have even given lectures about his life, his music and his medical problems (“Gustav Mahler – music, melancholia, and microbes”) It was only after hearing Mahler’s music a number of times that I understood why it took so long for me to treasure it; you need to be older and have experienced some of life’s travails to be able to understand the messages Mahler is sending.

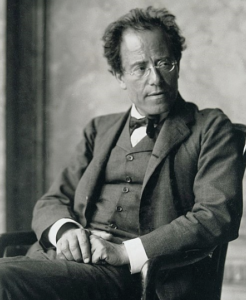

On July 7, 1860, in Kalischt, Bohemia, Gustav Mahler was born into a Jewish family of merchants. His great-great-grandfather, Abraham, was a ritual kosher slaughterer. Simon, his grandfather, had a distillery (one of the few businesses open to Jews at that time) which Mahler’s father, Bernhard, continued. Mahler wrote of his parents, Bernhard and Marie, “They belonged together like fire and water. He was all stubbornness, she gentleness itself.”

From childhood, Mahler was clearly a musical genius and clearly a bit different. A story told about him is that, at age 5, when asked what he wanted to be when he grew up, he responded “a martyr.” Mahler’s life is complicated and fascinating. Unqualified to summarize his physical and psychologic issues in a single diagnosis, I would note that he was an exuberant and fascinating friend to many, especially fellow musicians, while periodically depressed.

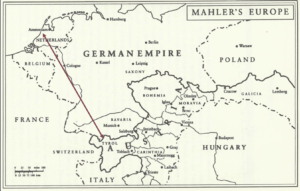

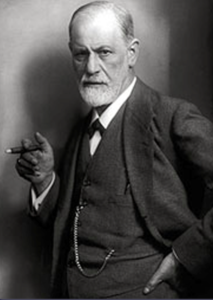

In his later years, he travelled from the Tyrol to Leiden, the Netherlands, to meet with Sigmund Freud

for only a few hours. Freud later wrote of the encounter, “I analyzed Mahler for four hours. He had strong obsessions, I can tell you.”

Among the many themes expressed by Mahler, both in his writings and, especially and deliberately, in his music, are death, fate, the strivings of the soul, the struggles of heroes, depression and more. While composing the 2nd he wrote to Natalie Bauer-Lechner, a confidante, “I went through the scherzo of my Second Symphony again; I haven’t looked at it since I first wrote it, and it absolutely amazes me. It’s a remarkable, fearful, great piece! I didn’t realize this when I was composing it.” When he completed the piece, he again wrote to her, saying, “My whole life is contained in my two symphonies. In them I have set down my experience and suffering, truth and poetry in words. To anyone who knows how to listen, my whole life will become clear.”

Mahler was 42 years old when he finally married. Alma Schindler (1879-1964), the daughter of the highly regarded impressionistic artist, Emil

Schindler, was labeled as the “supreme femme fatale” of early-20th-century Vienna. When still in her teens, she was described as Vienna’s most beautiful woman.

She likely lost her virginity to the artist Gustav Klimt and then had an affair with his friend and fellow artist, Alexander Zemlinsky. She married Mahler when she was 23 and he was 20 years older. She wanted to compose music, but Mahler initially discouraged her. When their marriage became troubled and she had an affair with Walter Gropius (the great architect and founder of the Bauhaus movement, who she met at a spa), he then encouraged her musical pursuits. Seventeen of her lieder (songs) have survived and are still performed. After Mahler’s death in 1911, she married Gropius who introduced her to

the writer, Franz Werfel (“Song of Bernadette”), who subsequently became her third husband. Other lovers included Oskar Kokoschka, a daring artist who, when their romance cooled, created a life-size fetishistic cloth model of Alma that he continuously carried with him for months, taking it to restaurants, concerts, exhibits, etc. Two films (Ken Russell’s Mahler and Bruce Beresford’s Bride of the Wind) and various Mahler biographies (Jonathan Carr: Mahler, 1998; Stuart Feder: Gustav Mahler-A Life in Crisis, 2004, Norman Lebrecht: Why Mahler? -How One Man and Ten Symphonies Changed our World, 2010 and others) are each fascinating but barely capture the complexity of this fascinating woman’s life. A recent biography, Passionate Spirit: The Life of Alma Mahler, 2019, by Cate Haste, is engrossing and exciting.

The American satirist Tom Lehrer, popular in the 1950s and 60s, described her obituary as “the juiciest, spiciest, raciest obituary it has ever been my pleasure to read,” prompting his ballad, “Alma,” which considers her marriage to Mahler as “Their marriage was murdah/He’d scream to the heavens above/”I’m writing Das Lied von der Erde/and she only wants to make love.”

One of the most interesting aspects of the life of Gustav Mahler is his death.

One of his two daughters, Maria Alma Mahler, known as “Putzi,” died at age 4 of scarlet fever and diphtheria. It may be that Gustav Mahler had rheumatic fever at that time, although it was not well documented. It is known, however, that some time after that a heart murmur was heard, evidence of heart valve damage. In 1910-1911, the year after he became Music Director of the New York Philharmonic heart failure developed and he sought the advice of Emanuel Libman, M.D., at New York’s The Mount Sinai Hospital. Libman was one of the finest physicians of his time and also a pioneering microbiologist, having studied in Vienna with Theodor Escherich (discover of Escherichia coli, E. coli). Libman understood, as only a few at that time did, that Mahler had a

condition then called Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis (SBE) and that he would be dead within in six months.

SBE is an infection of damaged heart valves, generally mitral valve first and then aortic, caused by the bacterium Streptococcus viridans. The valves are inflamed during Rheumatic Fever and then, years letter, deformed and fibrotic. Fibrin (a protein involved in the clotting of blood) deposits on the damaged valve(s) and becomes a nidus upon which the usually non-pathogenic S. viridans organisms can grow. Libman sent his young assistant, George Baehr, on the Fifth Avenue trolley from Mount Sinai to the Plaza Hotel, where Mahler lived, with equipment to obtain a blood sample which Baehr brought back to Libman’s laboratory. There they grew and identified the infectious agent. That focus of infection can break off and affect the brain, kidneys and other organs, as well as contribute to sepsis (generalized infection) but, more immediately, also worsens the heart failure already caused by the abnormal valves themselves. Libman understood that the process was relatively slow in developing, unlike endocarditis due to more virulent organisms, and that most patients lived 6 months after diagnosis.

Mahler resigned his directorship, sailed across the Atlantic to return to Vienna. He died at the age of 51, approximately six months after being diagnosed by Libman.

The third paragraph of this blog post includes a specific date—June 6, 2024, the 80th anniversary of D-Day, the invasion of Europe by the allied forces—particularly the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada—one of the greatest military operations ever. When I received the booklet of 2023-24 New York Philharmonic concerts last summer, that date immediately registered, as it would for so many of my generation and probably others raised in the 20th century, but, also probably, not known to younger people. It is a date indelibly etched in my mind, along with July 4, 1776, December 7, 1941, November 22, 1963, and many others. Immediately, it occurred to me that the Mahler 2nd was a perfect piece to commemorate D-Day, although there was no mention of this association in either that booklet or the program notes distributed at the concert.

Listening to the Mahler 2nd again on that date confirmed those feelings. This is the perfect piece for D-Day, an enormous topic too complex to discuss here (Cornelius Ryan’s The Longest Day is a highly readable way to learn about D-Day). D-Day should be celebrated every year and, to accompany it, the Mahler 2nd Symphony, the Resurrection Symphony, should be played by orchestras throughout the world. D-Day began in horror with mass casualties as the invading forces struggled to claim a foothold at Omaha and other beaches. It ended in triumph and signaled the beginning of the end for Nazi Germany. That is one of the themes of Mahler’s 2nd: horror’s transformation to celebration.

What are other messages of Mahler’s 2nd symphony? What do I often hear in those 90 minutes? Darkness and sunshine. Despair and redemption. Terror and tranquility. Suffering and relief. Grief and elation. Misery and exultation. Anguish and exhilaration. Desolation and rejoicing. Tragedy and elation. Horror and peace. Unbearable pain and glorious celebration.

Death and resurrection.

If you have never heard the Mahler Symphony #2, find a copy. Then, sit in a slightly dim and quiet room, alone and uninterrupted, perhaps with a glass of good red wine at hand, and feel the pain and then the resplendent resolution. It is the end. It is the beginning.

June 17, 2024 at 4:52 pm

Steve, thanks, from a felllow music and Mahler lover.

June 17, 2024 at 10:13 pm

Steve,

Wonderful to hear from you and glad you enjoyed the Mahler article.

June 17, 2024 at 7:43 pm

Thank you for such an interesting essay.

I was a little confused. Why play Mahler’s Second, which has as one of its themes “horror’s transformation to celebration,” immediately after the assassination of JFK?

I investigated and found Leonard Bernstein’s explanation that I thought I might share with you and your readers:

“There were those who asked: Why the Resurrection Symphony, with its visionary concept of hope and triumph over worldly pain, instead of a Requiem, or the customary Funeral March from the Eroica? Why indeed? We played the Mahler symphony not only in terms of resurrection for the soul of one we love, but also for the resurrection of hope in all of us who mourn him. In spite of our shock, our shame, and our despair at the diminution of man that follows from this death, we must somehow gather strength for the increase of man, strength to go on striving for those goals he cherished. In mourning him, we must be worthy of him.”

June 17, 2024 at 10:15 pm

Karen,

Thank you for the comment and, especially, for your detective work in identifying Bernstein’s explanation. I am sure it will be much appreciated by readers of my blog.