The first known physician was the Egyptian Imhotep, who is thought to have been active in the years close to 2625 BCE. He was the chancellor to King Djoser, high priest of the sun god Ra at Heliopolis and was the architect of Djoser’s step pyramid. The first inscriptions alluding to his medical abilities came more two millennia after his death in the Thirtieth Dynasty (c. 380-343 BCE). In this period there were also a few statues of him made and he was declared a god of medicine and healing.

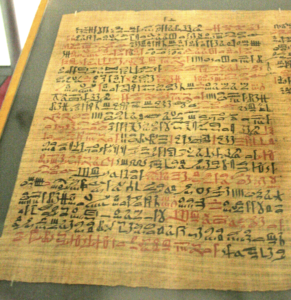

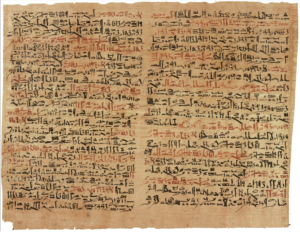

The oldest medical texts are six papyri from the period between 2000 BCE and 1500 BCE. These include the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, which mostly deals with trauma, and the Ebers Medical Papyrus, which concentrates on healing herbs.

Medicine and literature share a paradox – the requirement that one stand back from, and yet share in, the vicissitudes of human life. Doctors and authors document what they see. The physician, through historical review, examination, diagnosis and treatment chronicles the patient’s journey through the often-painful realities of life. The writer similarly considers the complexities of life and details the conflicts, challenges and arc of the human experience.

Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (1592) may be when we first hear of a doctor in fiction. Soon after Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1606-7) depicts an unnamed physician: Act V, Scene I, “Enter a Doctor of Physic and a Waiting-Gentlewoman.” The doctor (‘physic’ is the art and practice of healing) and the lady-in-waiting discuss Lady Macbeth’s walking at night and then hear her familiar words: “Out, damned spot! Out, I say!”

Since then, there have been many depictions of doctors in fiction, including Pasternak’s Yuri Zhivago (Doctor Zhivago), Arthur Conan Doyle’s John Watson (Sherlock Holmes), George Eliot’s Tertius Lydgate (Middlemarch), Albert Camus’ Bernard Rieux (The Plague), Mary Shelley’s Victor Frankenstein (Frankenstein), Thomas Harris’ Hannibal Lecter (The Silence of the Lambs), and Gustave Flaubert’s Charles Bovary (Madame Bovary), to name a few. Why are so many works of fiction based on medicine or law appealing to readers?

In recent years, many medical schools have tried to incorporate cultural activities, including literature, in the mass of scientific information they need to transmit to students.

In addition to the wealth of information provided students as a part of the regular curriculum, there often are a number of non-credit electives for which students can enroll, mostly specialty based. New York’s Mount Sinai School of Medicine, where I was a faculty member from 1971 to 1984, sponsored many electives. These were generally after the regular class hours or, for junior and senior students, with more flexible schedules, at various times in the day, usually held in the respective departments. As examples, there might be electives in some of the specialty clinics or an elective specifically devoted to chest x-ray interpretation or setting fractures.

In 1978-79, I offered “Medicine in Literature,” as an elective. It continued for six years until I moved to Los Angeles and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. We did not, in the Pathology department, have a conference room ideally suited for what I envisioned and I met with Jane Port, the director of the medical library to see if we could use one of the library’s meeting spaces. Highly informed and very well read , she enthusiastically agreed, offering to help with some of the administrative activities as well as participating actively in the discussions.

The format we followed was to select a novel or play in each of seven months. We tried to select a different specialty for each month and changed selections from year to year. The meetings were at the end of day and we provided soft drinks and snacks. Jane and I led the discussions and also invited another faculty member, whose area of special interest was the topic of the reading. The guest would participate with the provision that he or she had read the book along with the rest of us.

Each year, eight to ten students signed up for the elective. We thought discussions would be harder to manage with more than that number. We tried to pick books that were interesting and entertaining, that had medical aspects that would teach something, and that weren’t too difficult to read. Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain would be a good choice, but we were concerned it would demand too much time. Some other choices (e.g. Doctor Zhivago, Middlemarch) elicited the same concern. I prepared one or more ‘handouts’ to amplify topics discussed in the book.

The sessions were always very lively because the students were highly knowledgeable and the guest faculty provided considerable information and insights based on their own experiences in the practice of their specialty as well as from their life experiences. The sessions were uniformly exciting, challenging and invigorating.

One of my favorite novels since I first read it as a teenager is Of Human Bondage by W. Somerset Maugham. Maugham, a physician before he became one of the best-read writers of his time, led a fascinating life. A playwright, novelist and short-story writer, he was a spy during World War I. Of Human Bondage begins the tale of the orphaned Philip Carey at the time of his mother’s death. Much of this novel is based on Maugham’s life, including that Maugham’s  and Carey’s mothers both died of tuberculosis. Both are raised by an uncle, who was a Vicar, and his wife. In contrast to his own childhood home in Paris, which was warm and loving, the home of the fictional Vicar was narrow-minded and provincial, well depicted in the book. Philip Carey has a club foot, representing Maugham’s stammer. At age 16, Maugham traveled to Heidelberg to study. There he had his first sexual affair with an Englishman, ten years his senior. He did marry at one time, and had a daughter, Liza, but most his partners in life were men. Heidelberg and Paris are both prominent in the novel. In contrast to his life, the novel includes a number of close friendships with men, but no sexual liasons.

and Carey’s mothers both died of tuberculosis. Both are raised by an uncle, who was a Vicar, and his wife. In contrast to his own childhood home in Paris, which was warm and loving, the home of the fictional Vicar was narrow-minded and provincial, well depicted in the book. Philip Carey has a club foot, representing Maugham’s stammer. At age 16, Maugham traveled to Heidelberg to study. There he had his first sexual affair with an Englishman, ten years his senior. He did marry at one time, and had a daughter, Liza, but most his partners in life were men. Heidelberg and Paris are both prominent in the novel. In contrast to his life, the novel includes a number of close friendships with men, but no sexual liasons.

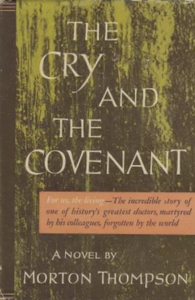

Have you ever heard of Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis?

Hardly anyone, including physicians and medical students, knows his name even though his contributions to medicine rank among the greatest and his name deserves to be spoken alongside that of Pasteur, Jonas Salk and Hippocrates. Semmelweis taught physicians to wash their hands, the single most-effective means of preventing the spread of infection. The Cry and the Covenant by Morton Thompson, is a highly readable, fascinating novel that tells the story of his life. A Hungarian, he came to Vienna to study medicine and became an obstetrician at the Vienna Lying-In Hospital specializing in caring for women in labor and delivering babies. He discovered the basis for the puerperal fever (sepsis) that ravaged newly delivered women and struggled, temporarily unsuccessfully, to teach his colleagues how to prevent it. For the discussion of this book, we invited an obstetrician to participate but could just-as-well have invited an infectious disease specialist.

life. A Hungarian, he came to Vienna to study medicine and became an obstetrician at the Vienna Lying-In Hospital specializing in caring for women in labor and delivering babies. He discovered the basis for the puerperal fever (sepsis) that ravaged newly delivered women and struggled, temporarily unsuccessfully, to teach his colleagues how to prevent it. For the discussion of this book, we invited an obstetrician to participate but could just-as-well have invited an infectious disease specialist.

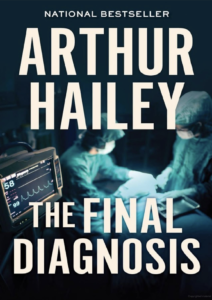

The Final Diagnosis by Arthur Hailey is another wonderful book from the list. There are only a few novels that focus on a pathologists as the principal character, rather than surgeons and other clinicians, but that is not the reason for reading this book. In a busy, rural general hospital, a number of characters, each with their own subplots, interact. Joe Pearson, the chief of pathology, was once an outstanding pathologist, regarded with near reverence by his clinical colleagues. But he has not kept up with the newest developments in clinical laboratory methods, including blood banking. He is joined by a young pathologist, David Coleman, and the story of their interactions helps the reader understand the concept of doubt and uncertainty in medicine. The book is also noteworthy in the way it highlights the role played by hospital administrators and a lay board of directors composed of community members. Indeed, the invited ‘expert’ who joined our discussion of this book was a hospital administrator. This book, as well as the influence of childhood experiences and mentors, may have been one of the reasons I chose the wonderful path of Pathology as a specialist. The title of the book, The Final Diagnosis, refers to the fact that the pathologist is usually the one to establish the final diagnosis when someone dies, but also emphasizes the critical role played by the pathologist in establishing diagnoses in living people from biopsy or surgically resected tissue samples. It also is about the diagnosis of a young nurse’s tumor about which Pearson and Coleman vehemently disagree. The 1961 film, “The Young Doctors,” based on this book, starred Frederic March and Ben Gazzara with an excellent supporting cast.

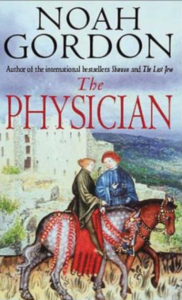

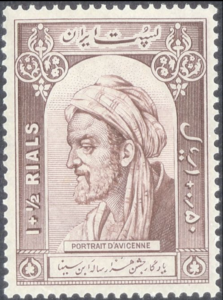

The Final Diagnosis by Arthur Hailey is another wonderful book from the list. There are only a few novels that focus on a pathologists as the principal character, rather than surgeons and other clinicians, but that is not the reason for reading this book. In a busy, rural general hospital, a number of characters, each with their own subplots, interact. Joe Pearson, the chief of pathology, was once an outstanding pathologist, regarded with near reverence by his clinical colleagues. But he has not kept up with the newest developments in clinical laboratory methods, including blood banking. He is joined by a young pathologist, David Coleman, and the story of their interactions helps the reader understand the concept of doubt and uncertainty in medicine. The book is also noteworthy in the way it highlights the role played by hospital administrators and a lay board of directors composed of community members. Indeed, the invited ‘expert’ who joined our discussion of this book was a hospital administrator. This book, as well as the influence of childhood experiences and mentors, may have been one of the reasons I chose the wonderful path of Pathology as a specialist. The title of the book, The Final Diagnosis, refers to the fact that the pathologist is usually the one to establish the final diagnosis when someone dies, but also emphasizes the critical role played by the pathologist in establishing diagnoses in living people from biopsy or surgically resected tissue samples. It also is about the diagnosis of a young nurse’s tumor about which Pearson and Coleman vehemently disagree. The 1961 film, “The Young Doctors,” based on this book, starred Frederic March and Ben Gazzara with an excellent supporting cast. The Physician by Noah Gordon is a 608-page epic novel that tells the story of Rob Cole, a Christian English boy in the 11th century, who is taken in by “Barber,” a traveling barber-surgeon, when his parents die. Rob becomes his apprentice and learns many skills to entertain people as well as the little the Barber knows of medicine. When Barber dies, Rob takes over the traveling medicine show but he becomes restless wanting to know more about medicine. After meeting a Jewish physician, who tells him where schools of medicine can be found, in Spain and as far away as Persia, where he might study with the Muslim Avicenna (Ibn Sina) – the pre-eminent philosopher and physician of his time, he decides he wants to learn more. He travels from London to Constantinople (now Istanbul). After learning Jews were generally allowed more freedom than Christians, he takes on the guise of a Jewish student and sets out to study with

The Physician by Noah Gordon is a 608-page epic novel that tells the story of Rob Cole, a Christian English boy in the 11th century, who is taken in by “Barber,” a traveling barber-surgeon, when his parents die. Rob becomes his apprentice and learns many skills to entertain people as well as the little the Barber knows of medicine. When Barber dies, Rob takes over the traveling medicine show but he becomes restless wanting to know more about medicine. After meeting a Jewish physician, who tells him where schools of medicine can be found, in Spain and as far away as Persia, where he might study with the Muslim Avicenna (Ibn Sina) – the pre-eminent philosopher and physician of his time, he decides he wants to learn more. He travels from London to Constantinople (now Istanbul). After learning Jews were generally allowed more freedom than Christians, he takes on the guise of a Jewish student and sets out to study with

Avicenna, traveling further East with a group of Jewish merchants. He eventually arrives in Isfahan where he tries, unsuccessfully, to enter the local medical school. A chance encounter with the Shah of Persia allows him to enter the school and study medicine. He later travels with the Shah’s army as far as India, practicing his medical skills. Marriage and children ensue. Avicenna’s death, and the conquest of Isfahan by a rival king, as well as conflict with the Shah, eventually drive him back to England and Scotland’s hills where continues to practice medicine. A worldwide success as a novel, the film of the same name, based on it, starred Ben Kingsley as Avicenna.

Side note: When I consider films based on novels, particularly long novels such as this one, I think of some of the great films of the 20th century, such as Ben Hur, Doctor Zhivago and others. But I also think of this episode from the television show “Cheers” when former baseball player/bartender Sam Malone (Ted Danson) has just finished a marathon reading of War and Peace, which he undertook to impress his girlfriend Diane (Shelley Long):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q7AqKRX3xaY

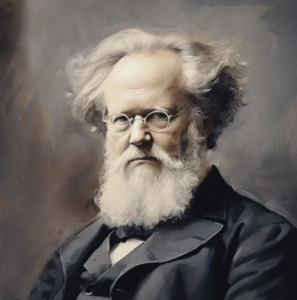

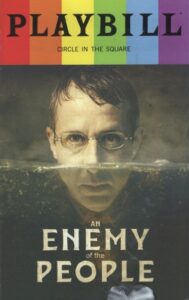

An Enemy of the People by Henrik Ibsen is a classic play dealing with the conflict between a principled physician-scientist and the commercial needs of his community. Dr. Thomas Stockmann discovers that the financially invaluable spa in his town is contaminated, posing a great public health risk for the community and the many tourists who bring outside money into the town’s coffers. Dr. Stockmann is vigorously opposed by local leaders, including his brother, Peter Stockmann, who is a powerful political figure. This 1882 play had its Broadway debut in 1950, starring Frederic March and Morris Carnovsky.

It was revised in 2012 for another Broadway run. An Enemy of the People, starring Jeremy Strong and Michael Imperioli, recently concluded a 2024 revival run. This is a particularly rich tale for medical students, dealing with public health and epidemiology but also with the moral obligations of a physician which may require him/her to withstand public pressure and financial ruin in favor of doing the right thing. In 2018, China cancelled a touring production after a very brief run in Beijing. The White Hotel by D.M. Thomas is a marvelous, fascinating and wondrous novel, with rich themes considered. There is heavy emphasis on Freudian philosophies. In addition, the Holocaust, including Babi Yar, is an important part of the plot. The narrative includes highly erotic portions in the form of letters between the principal female character and a fictionalized Sigmund Freud, which made me hesitate before offering it to young people. When I discussed this with a psychiatrist friend, the late and brilliant Hillel Swiller, he assured me that the medical students would be far less concerned about these things than I. He also offered to be the faculty person joining in the session which proved to be

The White Hotel by D.M. Thomas is a marvelous, fascinating and wondrous novel, with rich themes considered. There is heavy emphasis on Freudian philosophies. In addition, the Holocaust, including Babi Yar, is an important part of the plot. The narrative includes highly erotic portions in the form of letters between the principal female character and a fictionalized Sigmund Freud, which made me hesitate before offering it to young people. When I discussed this with a psychiatrist friend, the late and brilliant Hillel Swiller, he assured me that the medical students would be far less concerned about these things than I. He also offered to be the faculty person joining in the session which proved to be

one of the most interesting, particularly because of his participation. Hillel led a similar discussion group for a psychoanalytic society which concentrated on psychological themes in films. The White Hotel won several writing awards and was on the short list for the Booker Prize. A number of attempts were made to create a film but none came to fruition.

The Citadel by AJ Cronin (1937) and Sinclair Lewis’ Arrowsmith were once recommended as necessary readings for those wanting to go to medical school, a part of the mythology (along with the ideas you had to study German or Latin) offered for young people (mostly men at that time) when I was thinking about going to medical school. This was not of the same significance as taking organic chemistry as an undergraduate, but rather based on the premise that one must have a foundation in ethics and morality to be a capable and responsible physician. To the best of my knowledge, no one was asked about either of these wonderful novels during medical school interviews. I sometimes think my mother may have made it all up since she loved both books. Several physicians of my era certainly read one or both but I think most young physicians today have never heard of either of them and, indeed, recreational reading may not be something typically carried out by today’s young physicians.

Still, my mother, or whoever thought the myth up, was correct. These are informative and inspirational novels and should be read by every physician. The Citadel is thought to be the model for the United Kingdom’s National Health Service. The Citadel, published in 1924, tells the story of Andrew Manson, a highly motivated and idealistic recent graduate who comes to a Welsh mining village to begin practicing medicine. He quickly recognizes that the physician, to whom he has been assigned ,is unwell and partly disabled, requiring that Andrew do almost all the work for a pittance of a salary. He soon leaves and takes a position in a coal mining town, where he begins studying silicosis, with the help of his new wife, Christine, a teacher. He eventually publishes the results of his research and is offered a job in the ‘Mines Fatigue Board’ in London, but he resigns after a half-year to set up private practice, caring for pampered patients. When his wife is killed as a result of a bus accident, he abandons his practice and returns to his principles. After he sues his wife’s surgeon for incompetence, he suffers retaliation when he is reported to the medical council that he had worked with an American tuberculosis expert who lacked a medical degree and utilized techniques that had not yet been fully accepted, in particular the way to collapse a diseased lung (pneumothorax).

The Citadel, published in 1924, tells the story of Andrew Manson, a highly motivated and idealistic recent graduate who comes to a Welsh mining village to begin practicing medicine. He quickly recognizes that the physician, to whom he has been assigned ,is unwell and partly disabled, requiring that Andrew do almost all the work for a pittance of a salary. He soon leaves and takes a position in a coal mining town, where he begins studying silicosis, with the help of his new wife, Christine, a teacher. He eventually publishes the results of his research and is offered a job in the ‘Mines Fatigue Board’ in London, but he resigns after a half-year to set up private practice, caring for pampered patients. When his wife is killed as a result of a bus accident, he abandons his practice and returns to his principles. After he sues his wife’s surgeon for incompetence, he suffers retaliation when he is reported to the medical council that he had worked with an American tuberculosis expert who lacked a medical degree and utilized techniques that had not yet been fully accepted, in particular the way to collapse a diseased lung (pneumothorax).

British books were banned in Germany during World War II but copies of The Citadel could be found in almost every Berlin bookstore. In 1938, an excellent film based on this novel, starring Robert Donat, Rosalind Russell, Ralph Richardson and Rex Harrison, was released. Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis was published in 1925, ten years before Cronin published The Citadel. The American Sinclair Lewis was awarded the 1926 Nobel Prize for Literature (which he declined) for this novel. He was helped in its writing by Paul de Kruif, the science writer, who received 25% of the royalties. The book was published approximately 25 years after the release of the scathing Flexner Report (Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching). This report described the inadequacy of medical practice and medical education in the United States and Canada and sugested major reforms, particularly in terms of assuring that mainstream science be added to the curricula of medical schools.

Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis was published in 1925, ten years before Cronin published The Citadel. The American Sinclair Lewis was awarded the 1926 Nobel Prize for Literature (which he declined) for this novel. He was helped in its writing by Paul de Kruif, the science writer, who received 25% of the royalties. The book was published approximately 25 years after the release of the scathing Flexner Report (Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching). This report described the inadequacy of medical practice and medical education in the United States and Canada and sugested major reforms, particularly in terms of assuring that mainstream science be added to the curricula of medical schools.

Arrowsmith tells the story of the extremely bright and science-obsessed Martin Arrowsmith. From a small town in the fictional state of Winnemac, he eventually makes his way to the pinnacle of a prestigious New York City scientific foundation, under the guidance of Professor Max Gottlieb. In a time of turmoil he becomes involved with two women, insults Gottlieb and is suspended from the school. He marries (Leora) and moves to North Dakota where his wife’s family will support him as he tries practicing as a general practitioner. The rest of the story is highly complex with his struggling, unsuccessfully, to control an outbreak of plague which leads to the death of many people, including Leora. His scientific principles prevent him from treating people until after any potential therapy is thoroughly tested. Eventually, he abandons his philosophies and saves many lives although he considers himself as hypocritical for having betrayed his main beliefs.

Despite his self-recrimination, Martin is widely lauded and returns to New York where he is heralded as a hero and offered the directorship of the entire institute. He turns down the promotion, abandons his new wife and soon moves to Vermont to continue his research in the backwoods, telling his family he wants to be alone to continue his work.

Many regard him as a completely narcissistic ass for giving up most of society but his fierce commitment to science leads others to regard him as one of mankind’s great heroes. It is easy to regard him in a highly negative light because of all he leaves behind, but the book may leave you thinking otherwise.

Arrowsmith focuses on the richness and intellectual rewards of scientific research and medical ethics and is still cited as a classic science novel. It was often mentioned during the COVID-19 crisis.

In 1931, Ronald Colman (so perfect for priggish roles), Myrna Loy and Helen Hayes (“first lady of the American stage”) starred in the film which was nominated for four academy awards.

It is understandable how medicine often serves as a rich backdrop for writers to explore questions of morality and ethics. The environment, as well as the commitment required by those in the field, including doctors, nurses and ancillary staff, allows for the development of engrossing and challenging stories. Below is the promised list of books that amplify the potential of medicine to capture the reader’s attention. There are many more that could be added.

Author Title

Honoré de Balzac The Country Doctor

Jean-Dominique Barby The Diving Bell and the Butterfly

Pat Barker Regeneration

Mikhail Bulgakov (M.D.) The Master and Margarita

Albert Camus The Plague

Caleb Carr The Alienist

Anton Chekhov (M.D.) Selected Stories

Robin Cook (M.D.) Coma

Robin Cook (M.D.) Death Benefit

Patricia Cornwell Postmortem

Colin Cotteril The Coroner’s Lunch

Michael Crichton (M.D.) Andromeda Strain

AJ Cronin (M.D.) The Citadel

Michael Cunningham The Hours

Joan Didion The Year of Magical Thinking

Arthur Conan Doyle (M.D.) A Study in Scarlet

Arthur Conan Doyle (M.D.) The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

Jaclyn Duffin To See With a Better Eye

Alexander Dumas fils Camille

Margaret Edson W;t

George Eliot Daniel Deronda

George Eliot Middlemarch

Jeffrey Eugenides Middlesex

Gustave Flaubert Madame Bovary

Stephen A. Geller (M.D.) A Little Piece of Me

Lisa Genova Still Alice

Lisa Genova Every Note Played

Tess Gerritsen (M.D.) The Surgeon

Tess Gerritsen (M.D.) Last to Die

Jean Giono The Horseman on the Roof

Noah Gordon The Physician

Noah Gordon The Last Jew

Noah Gordon The Death Committee

Gerald Green The Last Angry Man

Arthur Hailey The Final Diagnosis

Sheri Holman The Dress Lodger

Khaled Hosseini (M.D.) And the Mountains Echoed

Anna Lee Huber The Anatomist’s Wife

Anna Lee Huber Mortal Arts

Henrik Ibsen An Enemy of the People

John Irving Cider House Rules

Kazuo Ishiguro Never Let Me Go

Venairin Kaverin Open Book

Sinclair Lewis Arrowsmith

Thomas Mann Death in Venice

Thomas Mann The Magic Mountain

Gabriel Garcia Marquez Love in the Time of the Cholera

W. Somerset Maugham (M.D.) Of Human Bondage

Ian McEwen Saturday

Nicholas Meyer The Seven Percent Solution

Spencer Nadler (M.D.) The Language of Cells

Larry Niven A Gift from Heaven

Sherwin Nuland (M.D.) The Doctor’s Plague

Boris Pasternak Doctor Zhivago

Walker Percy (M.D.) The Moviegoer

Judy Picoult My Sister’s Keeper

Oliver Sacks (M.D.) The Awakening

Oliver Sacks (M.D.) The Man Who Thought of his Wife as a Hat

Ferrol Sams (M.D.) Run with the Horsemen

Samuel Shem (Bergman, M.D,) House of God

Nina Siegel The Anatomy Lesson

Aleksander Solzhenitsyn Cancer Ward

Robert Louis Stevenson Dr. Jekyl and Mr. Hyde

Irving Stone Passions of the Mind

DM Thomas The White Hotel

Morton Thompson The Cry and the Covenant

Morton Thompson Not as a Stranger

Donovan Tracy (M.D.) The Glass Doctor

Abraham Verghese (M.D.) Cutting for Stone

Irvin Yalom (M.D.) When Nietzsche Wept

October 12, 2024 at 3:21 pm

If I may add my modest contribution…

The book « Prisoner of hope » is a fascinating biography of Dr. Moshe Prywes. Born in Poland, med school in Paris, Sent to a Goulag during WW II, in the age of 27 was the main surgeon, in charge of the health of 28,000 prisoners.

The founder and general director of the medical school in Be’er Sheba, Israel. Member of WHO, National Academy of Sciences, Rockefeller foundation, French legion of honor, a fascinating life.

Another book, which, unfortunately, was never translated to English, to my best knowledge, is « angels among the rocks ».

The book describes the life of Dr. Moshe Wallach, a German Orthodox Jew, who came to Ottoman Palestine in 1870, and offered « modern » for his time, medical service to the prîmitive little town of Jerusalem of those days. In 1900 he returned to Germany to raise funds for a hospital building, which changed the level of health services in Jerusalem. In 1916 he recruited Schwester Selma Meir, who came to Jerusalem and started the first nursing school in town. One of the major contribution of the two was introducing the importance of hygienics.

The official name of the hospital was «Sha’arey Tzedek », but everybody in Jerusalem called the hospital – The Wallach hospital. In 1980 it moved to a new facility and is a major medical center in the city , on top of Hadassa medical center.

Regarding Dr. Ignaz Zemelweiss – the Budapest med school is named after him. On top of it, the museum of medical history is located in the historical house Zemelweiss used to live in Budapest.

April 15, 2025 at 12:12 pm

Ze’ev,

Many thanks. I learned a lot. I have ordered the Prowess book but have not found the Wallach book.

I have long regarded Semmelweiss as one of the great heroes of medicine. I was in Budapest a few years ago but, to my great regret, didn’t remember to visit the museum.

Hope all is well with you and yours in this time of great America-induced turmoil. Our once great country is being led by a stupid man who hires people even stupider than he is to run the country. A bad time for us and for the world.

October 12, 2024 at 3:30 pm

This essay merits A+ and wide dissemination! I was delighted to see “A Little Piece of Me” included, as it is the only book on the list that I have. I may have read Arrowsmith and one or two others but I now hope to survive long enough to read several more.

October 12, 2024 at 4:08 pm

As long as we’re doing fictional or mythical doctors, let’s not forget the formidable Merit-Ptah! (Y’could look it up.)

October 12, 2024 at 4:16 pm

Not sure she qualifies. I thought she never existed. On the other hand, she does appear in some book (I have to look it up …). Still, thank you for reminding me about her. You may be the only one I know who actually read Arrowsmith and The Citadel …

October 14, 2024 at 10:17 pm

Oh, this is marvelous! I feel I’ve been in a graduate seminar. Thanks. I forgot that Maugham was a physician. Do you know his play, THE CONSTANT WIFE? It’s not at all about medicine but the male lead (the INCONSTANT husband) is a medical doctor and was played on Broadway by Michael Cumpsty!