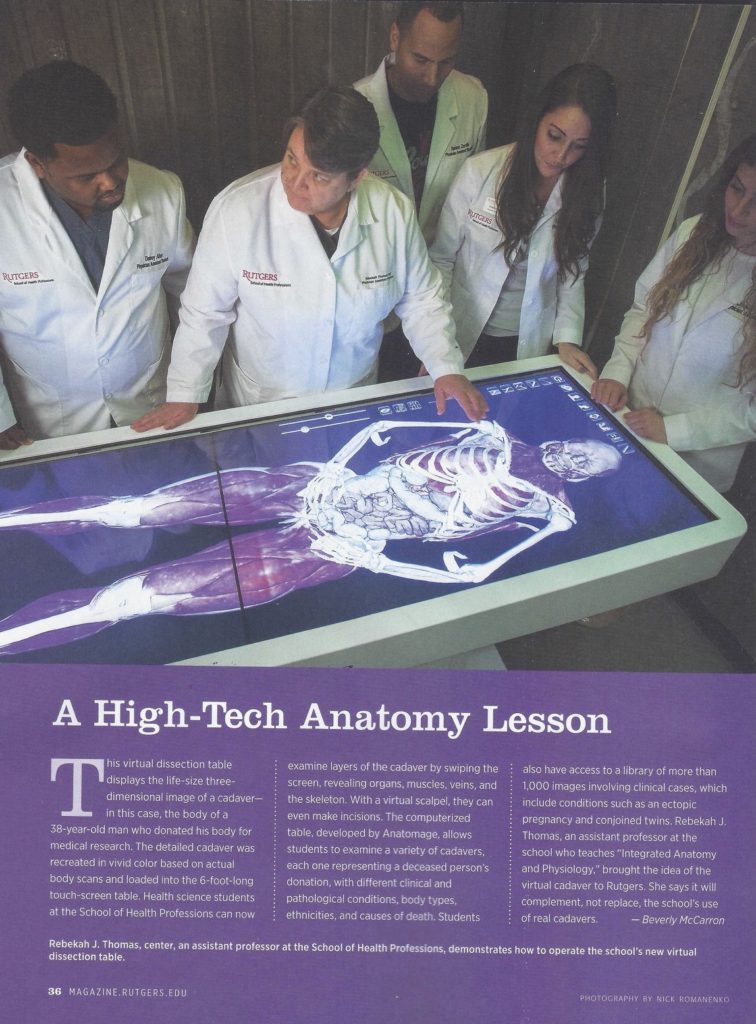

The Spring 2018 issue of Rutgers Magazine, the magazine for alumni of the State University of New Jersey (Kate, my wife, is a Rutgers graduate), includes a one-page article, A High-Tech Anatomy Lesson, describing how medical students can be taught human anatomy using virtual imaging technology (1). The article notes that this technology will “complement, not replace, the school’s use of real cadavers.” The reality is that the use of human bodies in teaching anatomy has, if you forgive the unintentional pun, a limited lifespan. Bodies are difficult to obtain and they are relatively costly. Most medical students are armed with iPads or other similar devices and will not want to deal with the actual hard work of dissecting relatively monochromatic, cold and smelly human bodies.

The Spring 2018 issue of Rutgers Magazine, the magazine for alumni of the State University of New Jersey (Kate, my wife, is a Rutgers graduate), includes a one-page article, A High-Tech Anatomy Lesson, describing how medical students can be taught human anatomy using virtual imaging technology (1). The article notes that this technology will “complement, not replace, the school’s use of real cadavers.” The reality is that the use of human bodies in teaching anatomy has, if you forgive the unintentional pun, a limited lifespan. Bodies are difficult to obtain and they are relatively costly. Most medical students are armed with iPads or other similar devices and will not want to deal with the actual hard work of dissecting relatively monochromatic, cold and smelly human bodies.

Other recent articles, in both medical journals and lay literature, have been even more emphatic in suggesting that actual human bodies to teach anatomy will be replaced either by virtual images, increasingly holograms, or by plastic models, including those created by 3-D printing the various body parts or, most likely, a combination of both images and manufactured structures (2-6).

After reading the Rutgers article I queried one hundred physicians via email––mostly pathologists (reflecting my email address list) but also internists, surgeons, and a smattering of other specialities––to solicit their views about their own medical school experiences in anatomy. With only a few exceptions they are all still in practice and busy so it is not surprising that I received responses from only twenty per cent. Most of those who responded concentrated on how well they learned anatomy and, accordingly, were skeptical of the use of artificial devices to teach anatomy.

Some of the respondents answered in terms of the autopsy (knowing my great interest in that topic) rather than about anatomy, but expressing similar concerns.

The story of the evolution of hospitals could be considered a tale of diminishing numbers of those who principally benefit from their existence; from all of society to handfuls of executives. There are fewer hospitals than there were a half-century ago; in 1975 there were 1,465,828 hospital beds in the United States and forty years later, in 2015, there were fewer than 900,000 – a drop of a half-million beds in less than a half century (7). Those that still exist in communities are often smaller than they once were. At the same time, hospitals that were already large, including many teaching hospitals, are becoming huge, either by expanding at an existing site or, often, becoming part of a multihospital system seeking economies of scale and concentrated expertise for highly sophisticated procedures and treatments. Hospital-based care is exceedingly expensive and, increasingly, hospital stays are brief and much care previously requiring hospitalization is now carried out on an outpatient basis. The total numbers of beds is not necessarily a concern although the distribution of beds is increasingly problematic (8).

Hospitals were originally created to protect the entire community by isolating the highly contagious and incurable. In that setting, they were for almost every one in society although they physically cared for only a few (9). Later, as knowledge improved and medical techniques developed, hospitals provided refuge for the those suffering from life-threatening disorders, especially infections in the centuries before antibiotics, and for those, beginning in the early- and mid-19thcentury, requiring care after surgical procedures.

Until the late 19thcentury, when pathologists began using the microscope in their studies of afflictions, it was not always possible to distinguish infections from non-infectious disorders. As example, the diagnosis of ‘linitis plastic,’ a term now synonymous with gastric adenocarcinoma, might have been applied for the macroscopic appearance of either gastric cancer or advanced syphilitic gastritis in those long-gone, pre-microscope years. As another example, lymph nodes with inflammatory changes were often confused with lymphoid malignancies until Thomas Hodgkin’s 1832 paper, On Some of the Morbid Appearances of the Absorbent Glands.Microscopy was not yet a part of medical practice and Hodgkin’s conclusion was based on his autopsy observations correlated with the signs and symptoms the patient displayed before death (“ … unless the word inflammation be allowed to have a more indefinite and loose meaning than is generally assigned to it, this affection of the glands can scarcely be attributed to that cause, since they are unattended by pain, heat, and other ordinary symptoms of inflammation.”) (10,11).

As more and more patients came to hospitals, physicians had the opportunity to exponentially learn about diseases and develop methods to treat those disorders and, for a period of time, from the early 19thcentury to the end of World War II, hospitals became places for doctors to thrive in the practice of their art, to continuously learn, to gain the trust and support of patients and families as well as their colleagues, to carry out invaluable clinical research, to pass their knowledge and experience on to medical students and young physicians and, increasingly in the 20thcentury, to accumulate wealth. Doctors were in charge of hospitals and, by and large, did well in that role, aided by nurses and supported by influential and prosperous community leaders who were often integral to the progress and development of the hospital and of medical education (12,13). After 1945, physicians increasingly focused on diagnosing and treating patients and were not particularly interested in managing the business aspects of increasingly large and complex medical centers; this led to the development of an entirely new industry: the medical administrator (alluded to above as the “guys in green eye shades;” metaphor for another, almost extinct, profession: the bookkeeper). In the beginning the medical administrator might have been exposed to the history and traditions of medicine; now that is no longer deemed important. In recent years, many hospital administrators have themselves begun to lose control as huge health systems, which may include many hospitals and other types of healthcare facilities (e.g. free-standing emergency services, imaging centers, independent laboratories, dialysis centers, neighborhood group practices, et cetera) developed. The role of the federal government has changed. In the quarter century after World War II, as the principal and relatively easy to obtain source of money under the Hill-Burton Act and other legislation, for building and renovation of hospitals and for creating new medical schools – the number of medical schools in the United States has almost doubled since 1960; as example, there were 81 medical schools in 1960 and there are now 141, with more in the planning. The Medicare Act made the government a major player in terms of healthcare funding.The active practice of medicine, as we approach 2019, is increasingly shaped mostly by corporations rather than physicians, with varying and intermittent influence by government agencies. Medical care considerations prompt a wealth of mostly uninformed political rhetoric. Financial considerations often play the dominant role (as my grandmother noted, “when they say it’s not the money, it’s the money”). As one example, most hospitals will contract for only one manufacturer’s hip prosthesis to achieve economies of scale. The role of the community leader has become primarily that of a fund-raiser with less and less influence on hospital policy.

Without getting into the question of access to health care, which is increasingly threatened in the post-Obama era, it is fair to say that extraordinary improvements have occurred in medicine, especially for the affluent in the big cities.

So, what is the issue? And what does it have to do with learning anatomy?

One of the respondents to my survey, a surgeon, highlighted how much the act of dissecting the cadaver contributed to his sense of humanity and his compassion. It was a surprise to me that very few of the respondents pointed to this since I have long felt, along with my surgeon friend, that learning anatomy was only a part of what I gained from spending long hours struggling to master the details of the structure of the human body and its seemingly infinite variations, very often in the evenings after class and on weekends. Sometimes a few other classmates were there. Most often only one other student joined me; fortuitously her alphabetically assigned (Ewing, Geller) cadaver was next to mine and we were able to continuously look from one table to the other and to continuously share what we were learning. Sometimes, especially weekends, I was by myself. Those long hours in that cold dissecting room, while identifying muscle origins and insertions, searching for the thoracic duct or the recurrent laryngeal nerve, or so many other structures, are among my most cherished medical school memories.

Renée C. Fox, a sociologist, has written extensively about the culture of medicine (14). She emphasized the importance of learning uncertaintyas vital in the development of the physician, underscoring that no matter how skilled and well-informed a medical student must be, mastery of all that is known in medicine is impossible. It is studying anatomy, with innumerable details and variations of structure, that students experience this type of uncertainty first and most intensely.

One of my medical school teachers, the great cancer surgeon LaSalle Lefall, would say, “There are two diagnoses you will never make, the one you forgot and the one you never learned about.” You can’t easily control what you forget but you can try and prepare for deficits in knowledge by trying to learn as much as possible. Of course, it is impossible to learn everythings but this (mythical) goal was an integral part of the tradition of medical education. When I was a medical student, from 1960 to 1964, it was acknowledged that no one could completely master all of the material but the implication was that you should try. That is not, of course, realistic and is not the general teaching today.

In anatomy we had a variety of sources to help us learn; Grant’s Atlas, the Netter illustrations, various illustrated anatomy texts and others, but at least some of us––”we few, we happy few”––felt obligated (perhaps ‘compulsed’ is the better word) to read Gray’s Anatomy cover-to-cover (I actually read it twice). Indeed, all through medical school some of us tried to read every (often ponderous) tome––physiology, pharmacology, pathology, medicine, surgery, et cetera––completely. I did read all of the clinical texts––medicine, surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics, gynecology, psychiatry, public health and others––but never managed to finish biochemistry or neuroanatomy.

Sadao Otani, the great surgical pathologist at The Mount Sinai Hospital, New York (from whom I, and generations of other pathology and surgery residents, learned so much), would be highly skeptical about the new ways to learn anatomy.

He would likely caution that the computer images or the models are all the same and, thereby, impose a false sense of certainty, instead of the reality of uncertainty. He was cautionary about pathologists accumulating study sets of microscopy slides because of the false impressions they might give that one could learn all of pathology by studying hundreds or thousands or more slides since the great requirement of being a pathologist is to understand the infinite variability of human beings; pathologists must start from uncertainty before achieving certainty. Pathology a matter of philosophy as well as science.

Will the brilliantly prepared virtual reality demonstrations or the finely crafted plastic models allow the students of today and tomorrow to comprehend uncertainty, to learn professional humility? Can students of the not-far-off tomorrow learn to comprehend the limits inherent in the practice of medicine without the cadaver? Many instructors will teach that lesson but I wonder if it will be as effective as spending months with a human cadaver.

For the great majority of medical students the anatomy laboratory is the first sustained contact with human death. I had been fortunate to see a few autopsies when I worked at New York’s Lenox Hill Hospital as an operating room technician before I went to medical school. I, had seen many, many surgical procedures and was familiar with the appearances of internal organs, including the brain. Still, those first days in anatomy, seeing human bodies laid out on rows of stainless steel dissecting tables (four students assigned to each cadaver), their faces and genitals covered until we were ready to dissect those areas, were, to say the least, striking. It took a few days to begin dissecting without preparatory moments of contemplation. It took many days, even weeks, to become accustomed to the lifelessness, the coldness of the tissues and, not least, the pervasive odor of the tissue preservative formalin, picric acid and other chemicals that inevitably accompanied us home.

Anatomy allowed us to fail in the futile pursuit of complete knowledge, but also allowed us to not fail. No matter how many hours I spent in the anatomy laboratory, including evenings and weekends, and despite my Gray’s Anatomy having innumerable underlined and highlighted words and phrases. I didn’t always get perfect scores on examinations, although I generally did quite well (after all the dissect, score and that was a moment of great exhilaration. That was the moment I really knew I would eventually be a physician.

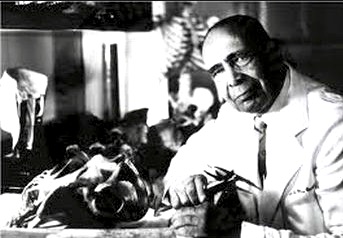

My anatomy experience was probably a little different than most. Our chairman, and principal instructor, was W. Montague Cobb, M.D., Ph.D., one of the most remarkable people I have ever known and a great influence on my life  and career, about whom I have previously written (15). Anatomist, renowned anthropologist, scholar, editor, poet, civic and civil rights leader, musician, linguist, historian, wit (often sardonic) and, most important, brilliant educator, Cobb’s lectures remain distinctly vivid. Before we began our dissections he taught us about palpation and percussion and some of us served as (somewhat reluctant) models as other students drew the outlines of the liver or spleen or heart on our bodies. Cobb had filmed all of many parts of the dissection with an old 8 mm movie film camera. These movies served as the basis for his lectures and to prepare us for our dissecting efforts.

and career, about whom I have previously written (15). Anatomist, renowned anthropologist, scholar, editor, poet, civic and civil rights leader, musician, linguist, historian, wit (often sardonic) and, most important, brilliant educator, Cobb’s lectures remain distinctly vivid. Before we began our dissections he taught us about palpation and percussion and some of us served as (somewhat reluctant) models as other students drew the outlines of the liver or spleen or heart on our bodies. Cobb had filmed all of many parts of the dissection with an old 8 mm movie film camera. These movies served as the basis for his lectures and to prepare us for our dissecting efforts.

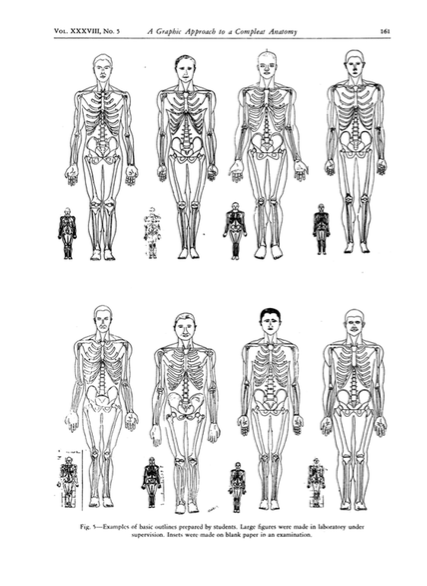

We were required to learn to draw the human skeleton in scale, according to the precepts of the artist Dürer who showed that the total length of the human body is 7.5 times the length of the head. Indeed, the dissecting manual Cobb wrote and distributed included many illustrations from art to highlight points (16). Our first examination  required that we draw the human skeleton in scale. Tests about the muscles, as example, required us to accurately draw origins and insertions.

required that we draw the human skeleton in scale. Tests about the muscles, as example, required us to accurately draw origins and insertions.

Cobb walked around the cadaver laboratory helping to identify otherwise elusive structures. He often helped with a difficult dissection, paying particular attention to those students who were relatively inept in learning anatomy. At the same time he would talk about medical history, about literature, about music, and more. He would quote Shakespeare when the occasion demanded it. A few times he would play his violin; usually Bach. He reminded us that anatomy, physiology and pathology are the foundations of medicine. He introduced us to Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), the great 16thcentury Padua anatomist, whose 1543 book, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem(The Structure of the Human Body in Seven Books; often referred to as De Fabrica) overthrew more than one thousand years of misinformation that was based on the teachings of Galen (129-200) whose anatomy dogma was mostly from dissections of Barbary apes and other animals (18).

Frequently Cobb would remind us to be grateful to the people from whose bodies we were learning. He would exhort us to remember them in the coming years and always be respectful to our living patients after we left the anatomy laboratory.

I do understand that my support for wanting to retain the dissection of the human body as a foundation of medical education is not entirely objective. And I also understand that newer methods will ultimately replace the cadaver as the way to learn anatomy, just as echocardiograms and other imaging devices may soon replace the stethoscope. Leo Gordon, a fine surgeon and a good friend, and a wonderful humorist, has written Out of Touch, about the increasing space between physician and patient with the development of new surgical instrumentation (19). His warm and gentle protest, laced with historical references and multi-smile-inducing allusions, bemoans the increase of the distance between surgeon and a patient’s diseased organ, at first with the advent of laparoscopic surgery and more recently with the increasing use of remote control of surgical tools (“robots”). Surely the science is better, but what about the art? There is benefit that can be appreciated, if not measured, when a physician “lays on hands.” Just feeling the pulse establishes an invaluable human-to-human link. And what happens when yet another of those “once-in-a-hundred-years” storms again hits and those robots don’t make it to dry land? point, what happens when the infinite variability of human experience demands direct contact.

A short poem comes to mind as I think about this fast-departing period in medical history:

My candle burns at both ends

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends –

It gives a lovely light.

Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950), A Few Figs from Thistles, 1920

Does today’s physician need to know as much anatomy as physicians who have gone before? Wouldn’t it suffice for the cardiovascular surgeon to just learn intensely about the cardiovascular system with only minimal exposure to the rest of the body? Why would he/she need to learn about the muscles of the hand? Does an ophthalmologist need to understand more than the anatomy of the eye and related structures? Does an orthopedist need to know in detail anything about the structure of the inner organs? Does a psychiatrist need to learn anything more than can be learned from a virtual teaching device or a plastic model?

I believe they do but I am not completely confident of my objectivity in deciding that and I am not confident I can convince others. But the point is not the tangible benefits but the intangible; the opportunity to think about death and mortality, about certainty and, especially, uncertainty.

What about the autopsy?

Can medical student participation in autopsies accomplish the same intellectual purpose as the dissection of the cadaver? Fox writes, “One of the chief consequences of the student’s participation in an autopsy is that it heightens his awareness of the uncertainties that results from limited medical knowledge, and of the implications those uncertainties have for the practicing doctor.” She spends considerable time documenting the importance of autopsy in the learning process of the medical student and, in 1988 when her book was published, autopsies were performed more often than now, is cautiously optimistic. Unfortunately the number of autopsies performed continues to drop––accurate numbers are not available any more but it is likely that fewer than 3% of patients dying in hospitals are autopsied–– and there has been a concomitant decline in the number of individuals skilled in autopsy performance (20). Indeed, many medical students and practicing physicians have never seen an autopsy and never become aware of the limitations of even the most skilled pathologists who themselves have performed a relatively few cases.

Of course, we gray-haired luddites will not make the decisions. Young practitioners, and students themselves, will favor newer, easier, probably (at least for them) more effective learning approaches (21). For many decades students and new residents have learned to pass endotracheal (breathing) tubes on either patients who just died (violating all sorts of current standards) or patients under anesthesia. Alternatively there are models of the upper airways now available that effectively simulate the real-life situation. Many other examples can be found.

I am confident that, on some distant day, teaching anatomy will no longer be necessary because there will be a device similar to that employed by Dr. Leonard (“Bones”) McCoy, the Chief medical officer aboard Star Trek’s USS Enterprise (NCC-1701).

Using a wireless hand-held device the physician of that far-off tomorrow will scan the entire body and learn the complete biologic history and current condition of the patient. Perhaps there will be another device to non-invasively treat whatever is detected, including fractures and hernias and everything else.

Until we can voyage to those distant galaxies, to paraphrase Tennyson, perhaps it is better to have learned anatomy and lost, rather than to have never learned at all …

Post script:

A few days ago three young medical student friends came to dinner at our house. They were from three different medical schools and at three different stages of their education; a first year, a second year and a senior applying for a residency in pathology.

Among the many things I think I heard:

- It’s not necessary to go to classes; “everything” is prerecorded.

- It’s not necessary to read books; everything you need to know can be found on your computer.

- Pathoma (“Sattar”), an online pathology textbook (https://www.pathoma.com/dr-husain-a-sattar) is the favorite resource for students studying pathology.

- Pathology residents in many programs want to have as many pathologists’ assistants (PAs) as possible employed so they can limit the number gross specimens they describe (this was definitely a shocker for me, almost causing of pain, cardiac and cerebral; in my residency years we would compete for specimens, especially those that were more complicated. Although I understand that this approach is inevitable and also pertains to other disciplines as more and more physicians’ assistants (also PAs) are used to examine and treat patients, I still have great concern – at least until we can order one of Dr. McCoy’s scanners …

References:

- McCarron, Beverly. A High-Tech Anatomy Lesson. Rutgers Magazine, Spring 2018.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ffKPiXSg940

- https://www.steadyhealth.com/articles/replacing-cadavers-in-medical-school-best-mobile-apps-for-learning-anatomy

- http://theconversation.com/why-virtual-reality-wont-replace-cadavers-in-medical-school-67448

- https://phys.org/news/2016-11-virtual-reality-wont-replace-cadavers-medical.html

- https://www.redorbit.com/news/health/1113190598/3d-printed-body-parts-may-replace-cadavers-training-071414/

- 7. https://www.statista.com/statistics/185860/number-of-all-hospital-beds-in-the-us-since-2001/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/29/upshot/a-sense-of-alarm-as-rural-hospitals-keep-closing.html

- Risse, Guenter B. Minding Bodies, Saving Souls – A History of Hospitals. New York, Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Hodgkin, Thomas. On some of the morbid appearances of the absorbent glands and spleen. Medical-Chirurgical Transactions (London), 1832; volume 17, pages 68-144.

- Geller, Stephen A. Comments on the anniversary of the description of Hodgkin’s disease. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, 1982; volume 49, pages 308-310.

- Starr, Paul. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York, Basic Books, 1983.

- Ludmerer, Kenneth. The Origins of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Journal of the History of Medicine, 1990; volume 45, pages 469-489.

- Fox, Renée C. Essays in Medical Sociology: Journeys into the Field, 2ndedition, New Brunswick, Transaction Books, 1988.

- Ehrlich JC. Sadao Otani, 1892-1969: a brief memoir. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, 1972; volume 39, pages 3-11.

- Geller Stephen A. Anatomy and the Bears. https://stephenageller.com/2014/08/16/anatomy-and-the-bears.

- Cobb, W. Montague. The Artistic Canons in the Teaching of Medicine. Journal of the National Medical Association 1944; volume 36, pages 3-14

- Geller Stephen A. Il Bo, the foundations of modern medicine are established. In Thiene G, Pessina AC (eds) Advances in Cardiovascular Medicine, Padova, Univ Degli Studi di Padova, 2002.

- Gordon, Leo A, Out of Touch, General Surgery News, April 2014, pages 14-15; https://www.generalsurgerynews.com/Opinions-and-Letters/Article/04-14/Out-of-Touch/27323

- Geller Stephen A. Who will do my autopsy?Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, 2015; volume 139, pages 578-580.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/31/education/learning/next-generation-of-caregivers.html?action=click&module=Editors%20Picks&pgtype=Homepage

November 7, 2018 at 11:45 pm

On target observations. Only time and trial and error will determine whether these changes will help or deter medical teaching progress.

Best to Kate and You.

Herbie (a dinasuar??)

November 8, 2018 at 1:16 pm

Thank you for a very informative, thought provoking blog post (as usual).

First, I want to say that physicians are notorious for their low response rates to surveys. I am not surprised that your response rate was so low. A few years ago, my husband, an epidemiologist colleague based at a US school of public health, and I surveyed chairs of epidemiology departments at US schools of public health using SurveyMonkey to learn more about the leadership of the field and its future. Many (if not most) of the epidemiology department chairs were physicians. As I recall, only two or three responded. (In any case, it was a small number less than five.) I am talking about epidemiologists who rely on surveys to conduct their own research but would not assist researchers trying to learn more about the field. Let that sink in for a moment.

As for the subject of your post, I recently read an article that quoted a surgeon who said that between the focus on computer games during childhood and the lack of shop classes (wood working, metal shop, etc.) in high schools these days, young surgeons are not entering residency with an ability to work with their hands. This is an ability that directors of surgery residency programs and senior surgeons in academia used to be able to take for granted. It used to be that teaching the technical skills of conducting surgery was the easiest part of teaching surgery residents. I am not so sure that is the case today. The hands-on experience of dissecting a cadaver might be more important today than it used to be, if young people aren’t getting the experience during childhood of working with their hands.

That said, isn’t it easier for students to “see” and learn about myriad variations in anatomy using computer technology, as long as these variations are included in the teaching material? Otherwise, students are dependent only on seeing the variations they find in their own cadavers or that are pointed out to them in other cadavers in the classroom. Computer technology should still play an important role in teaching anatomy. It’s just that it should not displace the experience of dissecting a cadaver.

November 11, 2018 at 12:41 pm

Excellent analysis of the disastrous eventual change in the teaching of human anatomy. I particularly liked the analogy with Dr. MaCoy’s tricorder that I often use in my clinical discussions when residents request full-body tomography for a patient who does not have such an easy diagnosis

November 28, 2018 at 12:12 pm

The cadaver is dying and may soon die but is fundly remembered

November 28, 2018 at 12:08 pm

Wonderful historical and current medical practices. My own recollections if I may:

I received my medical education in the mid to late fifties at the French Faculty of Mecine in Beirut Lebanon where we learned anatomy, physiology and pathology for 2 years before entering the clinical rotations, that was the old system of medical education.

I vividly recall the course of Anatomy consisting of two parts, detailed osteology and then body-organs morphology with parallel dissection. Professor Sarhal insisted on respect of the cadavers and the careful dissection of of the parts he has greatly described before, insisting on the anatomical variants and their importance in surgery. One of those variants was that of the bile duct and it’s different courses which I clearly remember. I learned and studied a lot for I wanted to be a surgeon but I ended being a pathologist after a reluctant compulsory rotation in Pathology. In autopsies I would try to identify some normal anatomical structures and landmarks.

Anatomy and histology are of course essential basic knowledge for a pathologist and these I acquired in the first two years of my medical education. This knowledge was indeed augmented as I practiced pathology thru autopsies, specimen description and slides examination.

I am retired now and I realize medical education and medical practice has changed dramatically but the old ways, careful dissection, careful autopsies, “exact” specimen descriptions and careful review of slides, have still a high value in reaching the proper diagnosis.

November 28, 2018 at 2:47 pm

well done, Steve…..much needed

some of the AP staff in my ‘former’ dept not only rely on path assistants for grossing but refuse to meet with liver transplant docs about their latest biopsy because they’re ‘too busy’

i would have locked them out instantly.

December 2, 2018 at 3:40 am

Hi, I am a third year medical student. During my time in medical school, my school decided to revamp the 1st and 2nd year curriculum, purchasing two Anatomage tables for ‘virtual anatomy’. Although as you stated, and I agree, it does not actually result in much significant learning of real anatomy via dissection, and one cannot get ‘a feel’ for the tissues as one would with a cadaver, though one of the effects I have noticed is that it has effectively roped in the radiologists into teaching anatomy. On the virtual anatomy tables, they are able to show their images and variations to the students. Perhaps the way this is going, more medical students will become interested in radiology with this shift in teaching methods. Regarding the point you mentioned about autopsies, I do think it is a valuable experience for medical students (at least it has been for me), in that it is much more vivid than dissecting formalin-preserved cadavers, though much more graphic. Though I will say that most medical students go through medical school without ever having been exposed to the autopsy. I did the post-sophomore fellowship in pathology at my school and even then I was only exposed to a small number of autopsies. I believe in some countries, students are required to observe an autopsy before graduating from medical school. This would be pretty difficult to implement these days with the declining rates of autopsy, however I do think it would be beneficial to setup a system for students to observe if willing.

December 3, 2018 at 1:07 am

Emily,

Thank you for your very thoughtful comment. As you appreciate the logistics of setting up a system for students to participate in autopsies can be difficult. When, however, a patient under your care dies and is autopsied it is always valuable and important to see that case and learn confirm your impressions, learn about errors, if any, and appreciate some of the other findings––not necessarily of clinical importance but still biologically of interest––that the autopsy discloses.