Jeopardy category: Medical trivia

Jeopardy answer: Johannes Lijdius Catherinus Pompe van Meerdervoort, the Netherlands

Correct response: Who established the foundation for modern medical practice in Japan and from what country was he?

Many writers—generally of a certain (relatively advanced) age or possibly confirmed Luddites—have pointed fearful fingers at the increasing (almost universal) reliance of those doing research and utilizing Google and other search engines, as well as to the public-at- large seeking information. The cries of alarm are meant to remind us that, among other advantage of seeking out original sources, so much can be learned by accident when looking through a book or other written research materials. The fear is that our store of knowledge will diminish if we do not make special efforts to expand it..

Others (and they may be correct) protest and say: au contraire, knowledge is increasing since it is now so easy to find information since we can find dozens of facts in the time previously required to find one.

Learned arguments can be found in each camp.

I am not anti-Google and other electronic sources (I often say that we each carry the world’s greatest library in our phones) but, deep down, I remain believer in the printed page.

Concerns emanating from my camp easily transform into metaphorical shrieks of pain as commercials becomes more and more of an online presence. As one example, when I type “psychology” into the search line the first thing that comes up is an advertisement for the current issue of Psychology Today. This is a journal I have periodically read but it’s not what I was looking for. If I bracket it with quotation marks—”psychology”—the yield is more than 33 million links, the first of which is “Top 5 Psychology Universities.” Also, not what I wanted.

When I open my Random House Unabridged Dictionary I immediately find the word I want, along with a concise definition and, to my great delight, a glance in any direction shows me things I never knew before. As one example, I don’t recall ever coming across the word “psychopomp.” It’s in the column to the right of “psychology. “Psychopomp is a noun referring to a person who conducts spirits or souls to the other world, e.g. Hermes or Charon. It comes from the Greek, psychopompós; conductor of souls.

Wow!

What an interesting and entertaining accidental discovery! I knew about Charon but was not aware of Hermes having a similar role (when I searched Hermes to confirm this role the first thing that comes up is “the official Hermès online store” and there are four other commercial links before I get to the Greek god, who the Romans called Mercury). Hermes “conducts spirits or souls to the other world” in the printed definition— the imagery is startling, even for someone who knows there are no spirits or souls or other worlds. Are there paintings, perhaps by Blake, that depict Charon? Indeed (demonstrating the incredible power of the internet). Charon appears in too-many-to-count works of art, including some by Blake, most easily available for viewing online.

Is psychopomp an important word I will often use? Probably not (although I will be delighted if it appears in a New York Times crossword puzzle some day). Still, great fun to find it!

In a similar manner I came across the name “Johannes Lijdius Catharinus Pompe van Meerdervoort,” as an entirely accidental encounter.

My favorite history of medicine text is the second English edition of Arturo Castiglione’s A History of Medicine (1), translated from the Italian by E.B. Krumbhaar, M.D., Ph.D., a great medical historian himself. It was last published in 1947 and is the one medical history text to which I refer most often, despite the fact that my bookshelf also contains most of the major medical history texts of the last fifty years.

Castiglione’s richly illustrated (albeit in grainy black and white) history, which, to a degree, encompasses the history of civilization and is an invaluable and much used resource. Whenever, in my other readings, I come across the name of an unfamiliar medical figure from the past I can usually find it in Castiglione’s book.

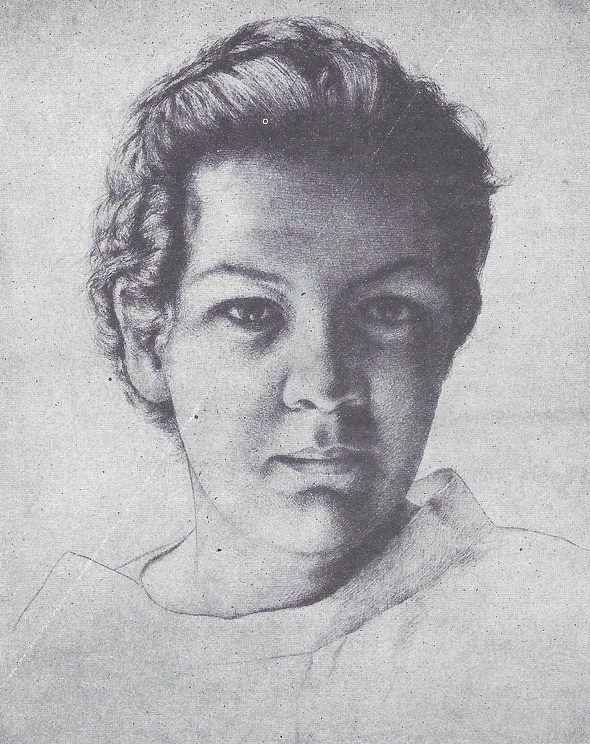

Castiglione, seen in this 1901 photograph, was born and raised in Trieste, Italy in 1874 (2,3). He earned the M.D. degree from the University of Vienna in 1896. He held chairs in the history of medicine in Siena, Perugia and Padua and achieved fame as Professor of the History of Medicine at the ancient University of Padua, whose halls had seen, either as faculty or student or both, Galileo, Andreas Vesalius, Copernicus, William Harvey, Morgagni and so many others who developed the foundations of modern medicine (4). A man of great culture, fluent in five languages, his lectures were said to “electrify” audiences (2). In 1939, unable to tolerate fascism and after refusing to join the fascist party when it became compulsory in Italian universities, he moved to New York with his wife and family and accepted a position as a medical historian at the Yale University School of Medicine, becoming an American citizen in 1946. He died, in Milan, in 1953.

Castiglione, seen in this 1901 photograph, was born and raised in Trieste, Italy in 1874 (2,3). He earned the M.D. degree from the University of Vienna in 1896. He held chairs in the history of medicine in Siena, Perugia and Padua and achieved fame as Professor of the History of Medicine at the ancient University of Padua, whose halls had seen, either as faculty or student or both, Galileo, Andreas Vesalius, Copernicus, William Harvey, Morgagni and so many others who developed the foundations of modern medicine (4). A man of great culture, fluent in five languages, his lectures were said to “electrify” audiences (2). In 1939, unable to tolerate fascism and after refusing to join the fascist party when it became compulsory in Italian universities, he moved to New York with his wife and family and accepted a position as a medical historian at the Yale University School of Medicine, becoming an American citizen in 1946. He died, in Milan, in 1953.

The second place I look for unfamiliar names or events is in Cecilia Mettler’s History of Medicine (5). Mettler was the first female professor of the history of medicine in the United States. Born in Weehawken,New Jersey in 1909, her father, William Charles Asper, was an attorney. She received an A.B. degree from the Convent of St. Elizabeth and went on to obtain a Ph.D. at Cornell University in 1938. During this period, she familiarized herself with medicine at the Washington University School of Nursing and the University of Georgia School of Medicine, where her husband, Fred Mettler, was a neurologist (Fred Mettler edited the final version of her textbook, published after her death). First appointed at the University of Georgia, she and Fred moved to New York in 1941 where she held a position as an associate in neurology at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Her major work, History of Medicine, reflects her philosophy that the teaching of medical history should correlate with the medical curriculum and includes many full translations from original Greek, Latin and Arabic sources.

first female professor of the history of medicine in the United States. Born in Weehawken,New Jersey in 1909, her father, William Charles Asper, was an attorney. She received an A.B. degree from the Convent of St. Elizabeth and went on to obtain a Ph.D. at Cornell University in 1938. During this period, she familiarized herself with medicine at the Washington University School of Nursing and the University of Georgia School of Medicine, where her husband, Fred Mettler, was a neurologist (Fred Mettler edited the final version of her textbook, published after her death). First appointed at the University of Georgia, she and Fred moved to New York in 1941 where she held a position as an associate in neurology at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Her major work, History of Medicine, reflects her philosophy that the teaching of medical history should correlate with the medical curriculum and includes many full translations from original Greek, Latin and Arabic sources.

Neither Castiglione nor Mettler mention Johannes Lijdius Catherinus Pompe van Meerdervoort. His name is not in Johann Hermann Baas’ Outlines of The History of Medicine and the Medical Profession (1889), translated by H.E. Handerson (6), Fielding Garrison’s An Introduction to the History of Medicine (7), Roy Porter’s The Greatest Benefit to Mankind (8), or any other history of medicine text. Yet, Pompe van Meerdevoort, a Dutchman, was one of the most influential medical educators of the mid-19th century who, along with Matsumoto Ryojun, a physician from the Japanese shogun’s court (9), established the first international medical school in Nagasaki, greatly influencing the development of modern teaching of medicine in Japan.

I “discovered” Pompe van Meerdevoort while preparing a paper and accompanying lecture: Doctors/Writers and their fictional patient – the language of illness and disease, in partial fulfillment of the degree requirement of the Master of Arts in Writing Program at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. Trying to fill out details about some of the physician writers I was planning to discuss, I turned to The History of Medical Education, edited by C.D. O’Malley (9). O’Malley was one of the great scholar of renaissance medicine, particularly Andres Vesalius. I have used O’Malley’s book before but it did not prove useful for the particular purpose of my paper. However, while browsing through the “M’ section of the index, looking for W. Somerset Maugham, one line captured my eye, at first because of its length—it jutted out a noticeably further than the names above and below—and then because of the name itself: Johannes Lijdius Catherinus Pompe van Meerdervoort

One of the most exciting, yet little known, achievements in the advancement of medical education in Japan was the establishment of the first international medical school at Nagasaki in 1857. This photograph shows Pompe van Meerdervoort surrounded by his students.

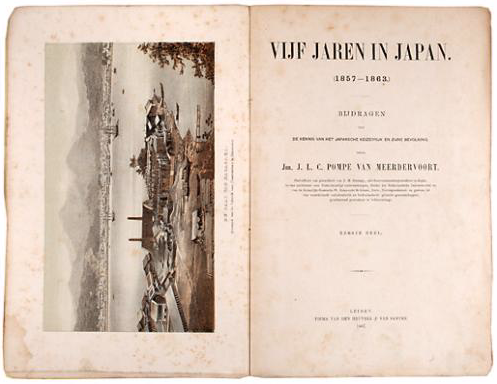

Nagasaki harbor, 1850 (note Dutch flags on the ships)

This pioneering school was the handiwork of Matsumoto Ryõjun, a Japanese physician, and Johannes Lijdium Catherinus Pompe van Meerdevoort, a Dutch physician based in Nagasaki (the target for the second atomic bomb in 1945). The westernization of Japanese medicine in the 19th century was largely due to the Dutch, who had a presence in Japan for more than two centuries.

In 1853, the shogun asked the Dutch for help in establishing a naval military school at Nagasaki. A Dutch frigate, the Soembing, with a detachment of naval officers to staff the new school, arrived first. A year later the Japanese sent a request for a second ship that would include the services of a Dutch physician to teach medicine. Pompe van Meerdevoort, a 28-year-old graduate of the military medical school in Utrecht, was chosen to be the medical officer; this turned out to be a most fortuitous selection.

Pompe van Meerdevoort was born in Bruges in 1829, one year after the separation of Belgium from the Netherlands. After completing his medical studies, in 1849, he was assigned to the East Indies, returning to the Netherlands after six years. In 1857 he was assigned to “the propeller ship, Japan,” for passage to the Dutch East Indies. Soon after the ship’s arrival in Nagasaki, the Netherlands Commissioner informed Pompe that the Japanese wanted students to be instructed in medicine and surgery. Pompe was advised to make whatever arrangements were necessary. From the beginning, despite not having an existing program on which to build, and without useful resources or any Western associates, Pompe was determined to establish a 5-year program, beginning with the premedical sciences, including anatomy, the study of which hardly existed. He proposed the development of a program in Nagasaki patterned after the best medical schools in Europe and, despite the great difficulties he encountered, he never wavered from that determination.

Shortly after Pompe’s arrival, Matsumoto Ryõjun, a 25-year-old physician to the shogun’s court in Edo (the former name for Tokyo), joined him. Ryõjun was a practitioner of Kampõ, traditional Japanese medicine, but had also learned a little about Western medicine from his distinguished physician father, Satõ Taizen, who had studied from European texts (10).

The first class convened on November 1857 and consisted of 12 students, none of whom knew Dutch; Pompe had not yet learned Japanese. Pompe’s predecessor as naval physician in Nagasaki, Jan Karel van den Broek, had devoted his energies toward creating a Dutch/Japanese, Japanese/Dutch dictionary but it never proved useful. Pompe lectured in Dutch with a translator at his side. Pompe recognized that there were many errors being made and arranged for an instructor from the Naval School to teach Dutch to the students. In the meantime, Ryõjun copied the translations to make them available to the students; he also prepared summaries of the lectures which he distributed in advance.

Despite the language problems, the number of students rose rapidly and, within the year, there were twenty studying the natural sciences (physics, chemistry, geology, mineralogy) and twenty-three studying medicine and surgery.

Pompe was a skilled physician. He performed the first human autopsy ever recorded in Japan, introducing the concept of clinical-pathologic correlations. Pompe’s student base rapidly expanded tomore than 130 students,  including a woman, Kusumoto Ine (1827-1903), whose fascinating story deserves its own telling but will only be briefly summarized here; she has been the subject of biographies, novels (11), television dramas, musicals and plays, almost all in Japan. Ine, who later in life took the name Ituko, was the daughter of the German physician Phillip

including a woman, Kusumoto Ine (1827-1903), whose fascinating story deserves its own telling but will only be briefly summarized here; she has been the subject of biographies, novels (11), television dramas, musicals and plays, almost all in Japan. Ine, who later in life took the name Ituko, was the daughter of the German physician Phillip  Franz von Siebold—a pioneering ophthalmologist who introduced cataract surgery and other advances to Japanese medicine—and his concubine, Kusumoto Taki.

Franz von Siebold—a pioneering ophthalmologist who introduced cataract surgery and other advances to Japanese medicine—and his concubine, Kusumoto Taki.  Siebold was banished from Japan when One was two years old; she and her mother were not permitted to leave Japan with him but Siebold, who was quite wealthy, always provided generously for them.

Siebold was banished from Japan when One was two years old; she and her mother were not permitted to leave Japan with him but Siebold, who was quite wealthy, always provided generously for them.

Ine began her medical studies in Okayama Domain under one of Siebold’s students, Ishii Soken. Soken is said to have raped and  impregnated Ine, leading to the birth in 1852 of her daughter Kusumoto Takaka (“Tada”). Ine severed all connections with Soken and never married.

impregnated Ine, leading to the birth in 1852 of her daughter Kusumoto Takaka (“Tada”). Ine severed all connections with Soken and never married.

Ine went on to study with other physicians including Pompe who wrote about her excellent performance. She became the first woman practitioner of Western medicine in Japan, concentrating on Obstetrics and Gynecology; she had a busy practice in Uwajima and Nagasaki and was highly regarded. The ruling lord of Uwajima provided her with a stipend and expected her to serve in the women’s quarters of the castle. She was one of the three doctors present when the lord’s wife gave birth in 1867.

The Nagasaki Naval Training Center was closed in 1860 and its Dutch staff withdrawn, with the exception of Pompe. At the time thousands of people were dying from a widespread cholera epidemic. In response to the ferocity of the disease, and at Pompe’s suggestion, the Tokugawa shogunate built Japan’s first western-style hospital, the Nagasaki Yojosho. Pompe was very highly regarded for his insistence on treating all patients equally, without regard to their social standing or wealth. This painting show Pompe awaiting the arrival of additional Dutch physicians.

Pompe was also a pioneering photographer; Daguerre had invented the first functioning camera when Pompe was just a child. Pompe gained a reputation as a teacher in this field also and one of his students became the first professional photographer in Japan and the first photographer to take pictures of an Emperor and Empress. A renowned botanist, as well as physician and photographer, Pompe spent five years in Japan, returning to the Netherlands in 1862, accompanied by two of his students who became the first Japanese citizens to study western medicine in Europe. Pompe wrote a book about his experiences: Five Years in Japan.

Pompe van Meerdevoort died in Brussels in 1908 when he was almost 80 years old but there is only minimal information available about his later years and his death. A street in Voorburg, near The Hague, Pompe van Meerdervoortstraat, was named after him.

References:

1. Castiglione, Arturo: A History of Medicine, 2nd ed, translated by E.B. Krumbhaar. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1947.

2. Fulton, John F. Arturo Castiglione 1874-1953. Bulletin of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, volume 8, pages 129-132, 1953.3. Kunstler, Margaret. A tribute to Dr. Arturo Castiglioni On the Occasion of his 70th Birthday. Canadian Medical Association Journal, volume 50, pages 371-372, 1944.

4. Geller, Stephen A. Il Bo, the foundations of modern medicine are established. In Thiene G, Pessina AC (eds). Advances in Cardiovascular Medicine. Padova. Univ Degli Studi di Padova, 2002.

5. Mettler, Cecilia C: History of Medicine. Philadelphia, The Blakiston Company, 1947.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cecilia.Mettler.

6. Handerson, HE (translator): Outlines of the History of Medicine and the Medical Profession by Joh. Hermann Baas. New York, J.H. Vail & Co., 1889.

7. Garrison, Fielding H: An Introduction to the History of Medicine, 4th ed. Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders Company, 1929.

8. Porter, Roy: The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, New York, W.W. Norton & Company, 1997.

9. O’Malley, C.D. The History of Medical Education, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1970; pages 409-412.

10. https://wiki.samurai-archives.com/index.php?title=Sato_Taizen

11. Yoshimura, Akira (translated by Richard Rubinger). Siebold’s Daughter – a novel. Portland, ME, MerwinAsia Publishers, 2016.

June 20, 2019 at 5:30 pm

facinating. Who knew?

Keep that mind churning

June 21, 2019 at 7:13 am

Dr. Geller, wonderful story, thank you for writing it. Very interesting history about Japan and Lijdius Catherinus Pompe van Meerdervoort.

June 24, 2019 at 6:54 am

Dear DR Geller

Excellent text. Very nice to read it and learn. Thank you for introducing me outstanding names of the history of medicine.

I would like you to insert the name of Prof Savassi (Luis Otavio Savassi Rocha in your email list losavassirocha@gmail.com

My best Regards