from the John Boorman film, “Excalibur”

from the John Boorman film, “Excalibur”

Few stories are better known in the Western world than that of King Arthur. In a previous blog post we commented, in some detail, on that legend (1). Who has not heard of this noble ruler—great warrior and benevolent sovereign—who created the Round Table so all knights would be equal, for whom chivalry and the protection of the poor was paramount, who defended the faith and created a united kingdom? Who has not heard of Guinevere, of Lancelot, of their tragic love that deeply hurt Arthur who they each, in turn, loved? The great sword Excalibur? Gawain and Bors and Galahad and all the other noble knights? Of the villainous Mordred? Of Merlin the wizard? Who does not know of the isle of Avalon where Arthur is said to still live? Or of the debate about whether he ever lived at all?

Soon after learning to read reasonably well, before I encountered Black Beauty or the Hardy Boys, I was introduced to King Arthur. For each special occasion, such as a birthday or Christmas—my grandmother, although a Jewish immigrant from Ukraine/Russia, insisted we celebrate what she considered an important American holiday—my mother would buy for me a beautiful hardcover illustrated version of a classic novel, abridged for young people. Living in a blue-collar neighborhood, we were far from wealthy and I understood those books were a significant expenditure; none of my friends received books under their trees.

The Arthur book I first read—The Boys King Arthur, retold by Sidney Lanier and beautifully illustrated by N.C. Wyeth— was heavily influenced by Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur (based on 13th century French tales; in Malory’s time the French wrote “of Arthur” as “Darthur” rather than “d’Arthur”). Despite the French title, Malory’s was the first great English language book to retell the Arthur legends Malory (1416-1471) wrote it while in prison for thefts and rapes, but that’s a whole other story. The book was published by William Caxton in 1545, seventy-five years after Malory’s death. Malory originally entitled it: The Hoole Book of Kyng Arthur and of His Noble Knyghtes of The Rounde Table and it is not clear what prompted Caxton to retitle it, but I am reasonably sure we are all grateful he did.

was heavily influenced by Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur (based on 13th century French tales; in Malory’s time the French wrote “of Arthur” as “Darthur” rather than “d’Arthur”). Despite the French title, Malory’s was the first great English language book to retell the Arthur legends Malory (1416-1471) wrote it while in prison for thefts and rapes, but that’s a whole other story. The book was published by William Caxton in 1545, seventy-five years after Malory’s death. Malory originally entitled it: The Hoole Book of Kyng Arthur and of His Noble Knyghtes of The Rounde Table and it is not clear what prompted Caxton to retitle it, but I am reasonably sure we are all grateful he did.

Almost a millennium before Malory, the earliest mention of an Arthur-like figure, Ambrosius Aurelianus, the son of Romans, was by Gildas (~500-570), a 6th century monk. Although Gildas never used the name “Arthur,” the similarities are obvious. The earliest written use of “Arthur” is in the Y Gododdin, an early Celtic poem from North Britain written somewhere between the 7th and 11th centuries. The poem refers to Arthur only indirectly when describing a great and generous warrior, Gwawrddur, noting his many admirable qualities with the caveat, “though he was not Arthur.”

“ … pierced more than three hundred of the finest.

He struck at both the center and the flank.

He was worthy in the front of a most generous army.

He gave out gifts from his herd of steeds in the winter.

He fed black ravens on the wall

Of a fortress, though he was not Arthur.”

The dark ages likely saw countless poems and stories told from village to village in which Arthur’s virtues and accomplishments were recounted.

By the end of the 6th century, at least four royal houses of Britain named their firstborn sons “Arthur.” The History of the Britons, written by Nennius in 880, describes a great battle at Baden Hill won by a warrior named Arthur leading other kings and, by the 11th century, when Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain is published, Arthur is popularly referred to as the “King of all Britons.” A number of stories in the late dark ages, on the continent and in Britain, including the Welch Mabinogion, allude to an Arthur. The first Arthurian romance (as opposed to a supposed historical account) (2) was by the French author, Chrétien de Troyes, who, in 1181, introduced Lancelot and his romance with Guinevere, including Wace’s concept of chaste, courtly love.

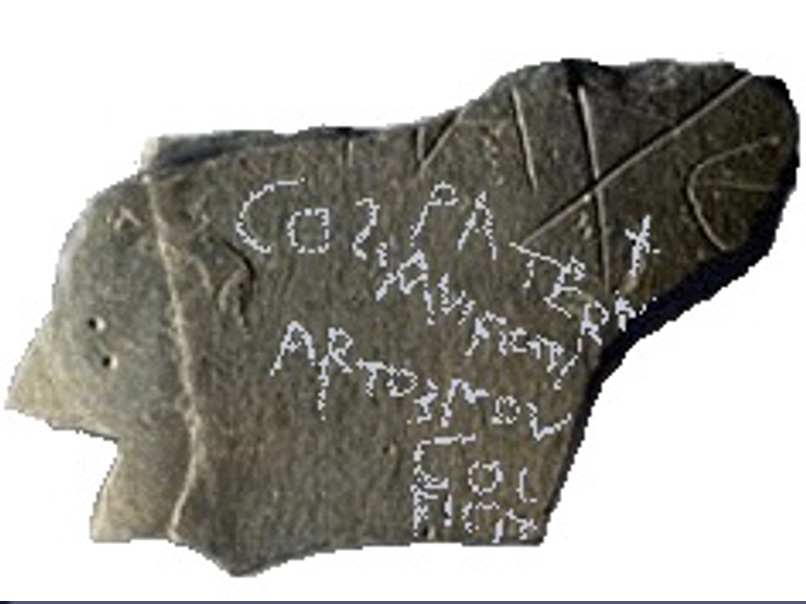

In 1998, the Artognou stone (still often erroneously referred to as the Arthur stone), an archaeological artifact, was discovered at Tintagel in Cornwall (3). Tintagel,  now a remnant of a castle, sits on a cold and windy hill on the southwest coast of Britain, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. Tintagel has long been considered by many to be the place of Arthur’s birth since it was mentioned by Geoffrey of Monmouth, Sir Thomas Malory, Alfred Lord Tennyson and others, despite the fact that there is no statement that Tintagel was the place of his birth, only that he was conceived there.

now a remnant of a castle, sits on a cold and windy hill on the southwest coast of Britain, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. Tintagel has long been considered by many to be the place of Arthur’s birth since it was mentioned by Geoffrey of Monmouth, Sir Thomas Malory, Alfred Lord Tennyson and others, despite the fact that there is no statement that Tintagel was the place of his birth, only that he was conceived there.

The most widely accepted version tells of Uther Pendragon, a warrior king who falls in love with Igraine, the wife of Gorlois, head of a neighboring kingdom. Gorlois defends himself against Uther and sends Igraine to Tintagel Castle, which he considered a completely safe refuge. In Geoffrey’s tale, Uther’s friend, Ulfin, tells Uther that it would be impossible to take Tintagel, since “it is right by the sea, and surrounded by the sea on all sides; and there is no other way into it, except that provided by a narrow rocky passage—and there, three armed warriors could forbid all entry, even if you took up your stand with the whole of Britain behind you.” Uther beseeches the wizard Merlin to help. Disguised by Merlin to resemble Gorlois, Uther enters Tintagel and goes to Igraine, and “in that night was the most famous of men, Arthur, conceived.”

The most widely accepted version tells of Uther Pendragon, a warrior king who falls in love with Igraine, the wife of Gorlois, head of a neighboring kingdom. Gorlois defends himself against Uther and sends Igraine to Tintagel Castle, which he considered a completely safe refuge. In Geoffrey’s tale, Uther’s friend, Ulfin, tells Uther that it would be impossible to take Tintagel, since “it is right by the sea, and surrounded by the sea on all sides; and there is no other way into it, except that provided by a narrow rocky passage—and there, three armed warriors could forbid all entry, even if you took up your stand with the whole of Britain behind you.” Uther beseeches the wizard Merlin to help. Disguised by Merlin to resemble Gorlois, Uther enters Tintagel and goes to Igraine, and “in that night was the most famous of men, Arthur, conceived.”

The slate Artognou stone is only 35 cm by 20 cm, and 1 cm thick, and has been dated back to the 6th century.

Kevin Grady, one of the discoverers of the stone, recalled, “As the stone came out, when I saw the letters A-R-T, I thought uh-oh …” Others, at the time, hailed the discovery as definitive proof that Arthur existed and that he lived at Tintagel. Many years ago, visiting Tintagel with my family, two decades before the Artognou stone was discovered, the sight of that bare promontory in a place with weather too harsh to support anything but the most minimal vegetation, I became convinced I was standing where Arthur began.

Kevin Grady, one of the discoverers of the stone, recalled, “As the stone came out, when I saw the letters A-R-T, I thought uh-oh …” Others, at the time, hailed the discovery as definitive proof that Arthur existed and that he lived at Tintagel. Many years ago, visiting Tintagel with my family, two decades before the Artognou stone was discovered, the sight of that bare promontory in a place with weather too harsh to support anything but the most minimal vegetation, I became convinced I was standing where Arthur began.

Unfortunately, for those of us who love the idea of Tintagel, of Uther and Igraine, recent scholarly studies (3) have led to the conclusion that the correct translation of the remnant inscription does not refer to Arthur at all and, instead, says: “Paternus son of Colus erected this to the memory of Artognou.” Artognou himself remains unknown, kindly remembered by his descendants in an inscription on a stone that, at one time, may have covered a drain in an ancient castle where imagination long ago outgrew reality.

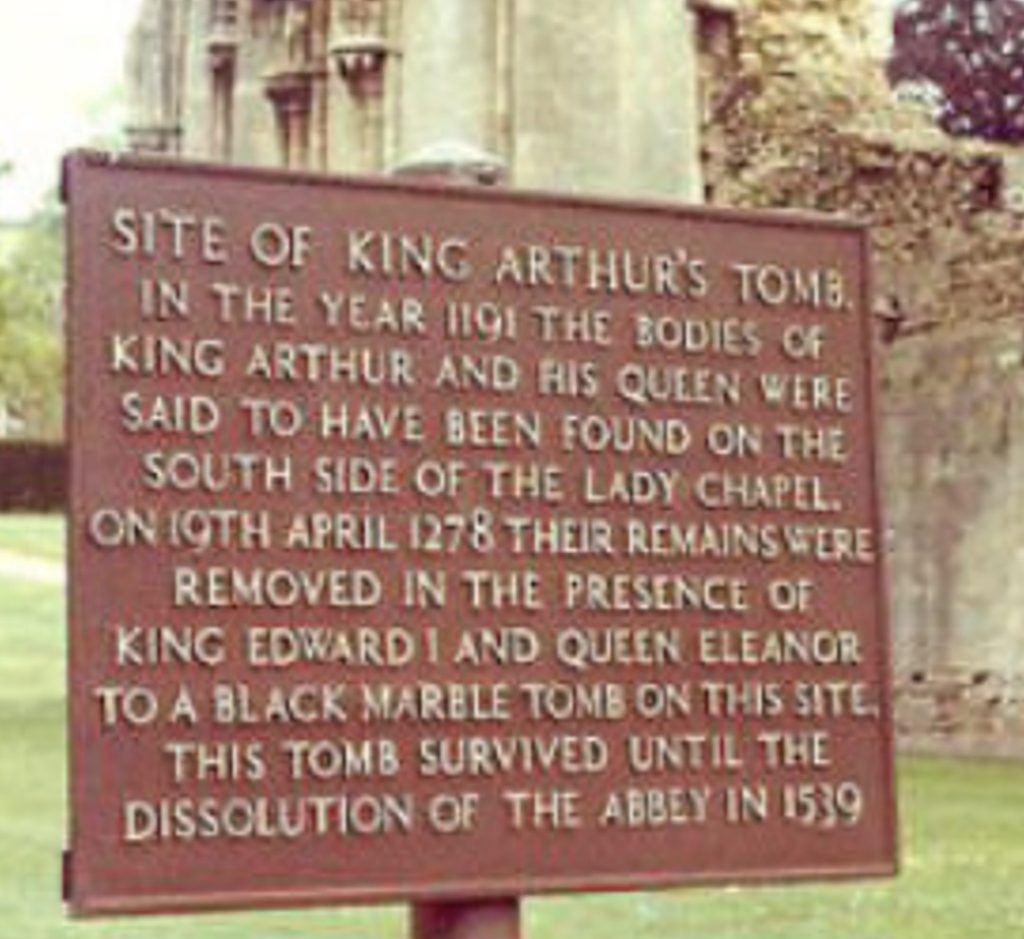

Further evidence often cited to prove the legend is the historical note that Arthur and Guinevere’s grave was  discovered at what is now Glastonbury but in the 6th century was a marshland known as Avalon. A wooden plate, inscribed Hic jacet sepultus inclitus rex Arturus in insula Avalon (here

discovered at what is now Glastonbury but in the 6th century was a marshland known as Avalon. A wooden plate, inscribed Hic jacet sepultus inclitus rex Arturus in insula Avalon (here lies interred the famous King Arthur on the Isle of Avalon), was in the grave, placed over the bones of a tall warrior, interred over a woman’s bones, including a lock of golden hair. On the back of the plate was inscribed: “with his second wife Weeneverela.”

lies interred the famous King Arthur on the Isle of Avalon), was in the grave, placed over the bones of a tall warrior, interred over a woman’s bones, including a lock of golden hair. On the back of the plate was inscribed: “with his second wife Weeneverela.”

Wow!

Pretty impressive!

Pretty convincing!

Unfortunately, the bones and the plate were moved by Henry II (1133-1189) to the adjacent cathedral. Four centuries later, the cathedral was destroyed during the period of Henry VIII’s attacks on the clergy and all its contents were lost. This story is more completely told in the previous blog post, “He is our King – the birth and death of King Arthur as told through the ages” (1).

During my childhood I received many other books for holidays and birthdays, including Dumas’ The Three Musketeers, Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, Twain’s Tom Sawyer and more, but King Arthur remains particularly important for me because of the magical story of the sword in the stone, of Arthur’s innate goodness and courage, of his ability to unite warring kingdoms, or his all too human weaknesses and, not least, because Arthur is my middle name. Over the years, I have read many of the novels written about him, almost all of which followed, at least to some degree, Malory’s depiction. I have seen most of the films based on those stories; a few (Excalibur, The Fisher King, the musical Camelot) are outstanding, thoughtfully conceived motion pictures, well worth seeing, but many are dreadful. Books and films about Arthur are also considered in more detail in the previous post (1).

Although there is still some controversy about whether or not Arthur actually existed at all, Arthur remains one of the best known historical figures.

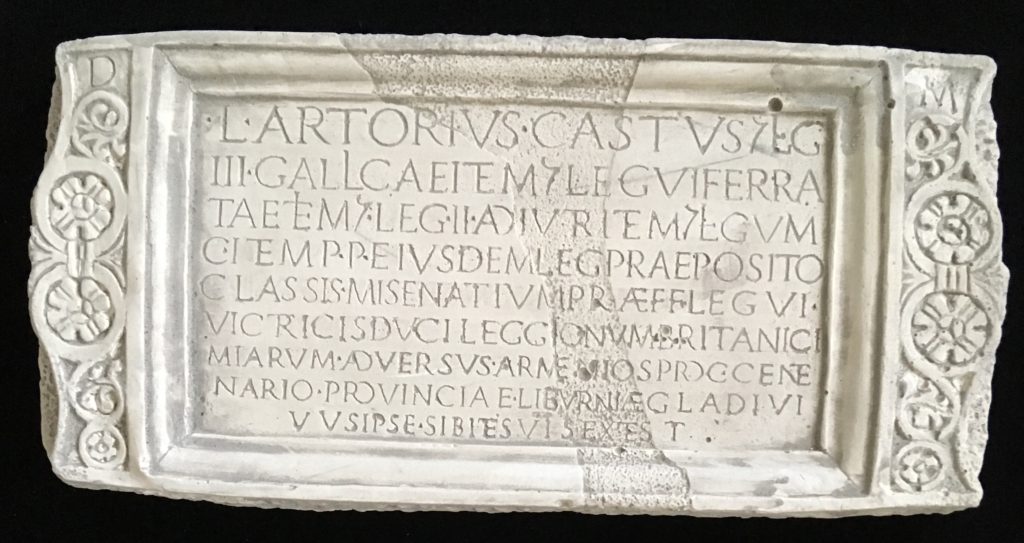

But, in a different part of the world and in an earlier century there is another, almost completely unknown Arthur story. This Arthur—Lucius Artorius Castus—was a Roman warrior from the 2nd century who was buried in one of the outreaches of the Roman Empire (4-8). Large fragments of stone bearing his name were found more than a hundred years ago in what is now Podstrana, a village

The Adriatic as seen from the Church of St. Martin’s, Podstrana, Croatia

approximately 15 kilometers from the port city of Split, on Croatia’s D8 roadway. A few weeks ago I was traveling through Croatia with my wife and daughter and I managed to steal an hour away to visit Podstrana. The day had been full with touring and my wife, Kate, stayed behind to read a good book, while my intrepid fellow-explorer, our daughter Jennifer, and I managed to convince Nick, a Split taxi driver, to take us there.

The late August early evening was hot and humid and, during the 30 minute drive we learned Nick had never heard of Arthur or Artorius. In fact, he became so intrigued by the story, perhaps buoyed by our enthusiasm, he elected to join our quest and follow our explorations.

Podstrana, an unhurried, welcoming hamlet, is a lovely strip of land along the Dalmatian coast of the Adriatic. A beach town receptive to visitors, I was immediately enamored by this seemingly undiscovered gem; there seemed to be mostly Croatians and Italians, with very few Americans. I immediately felt I should visit it again, when I would have more time.

The high-steepled Podstrana church we came to first was not the Church of St. Martin we were seeking but, after Nick made a phone call, we found our goal just down the road. The Church of St. Martin’s, Podstrana, is where the Artorius stone rests. When it was first recovered the stone was broken and it’s two largest portions were a part of the church’s outer wall.

The wall with two large fragments of the Artorius stone; the left fragment below is to the wall’s right and the right fragment below is to the left.

St. Martin’s Church has a single room, much smaller than the average theater. It is minimally adorned with a few religious paintings. The wooden pews were empty when we were there. To the right, just past the church cemetery, is the beautiful, placid, blue Adriatic Sea. The two portions of the Artorius stone have been brought together and now rest inside the church.

We were met by Denis Jonjic, a seasoned scholar and historian, and Karla Kristic, a young archaeologist from Split.  They had been informed that we would come late in the afternoon after our small cruise ship, the Mama Marija, docked. Denis and Karla proved to be wonderfully gracious and decidedly knowledgeable and, as soon as we met, I regretted not having more time to spend with them. Denis presented me with a wonderful replica of the reconstructed Artorius stone

They had been informed that we would come late in the afternoon after our small cruise ship, the Mama Marija, docked. Denis and Karla proved to be wonderfully gracious and decidedly knowledgeable and, as soon as we met, I regretted not having more time to spend with them. Denis presented me with a wonderful replica of the reconstructed Artorius stone  as well as plaque showing a profile of Artorius as commander of the fleet in Misenum (more about that below).

as well as plaque showing a profile of Artorius as commander of the fleet in Misenum (more about that below).

On the stone some details about Artorius’ life are inscribed. More have been uncovered by searching ancient Roman records.

During the reigns of Emperor Hadrian (117-138) and his successor Emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161), Artorius performed important duties in five different regions and was once a part of the imperial war fleet. He started as a centurion and eventually served as Governor of the province of Liburnia, in Dalmatia, where he finally retired and was buried. As a young man, in Hadrian’s time, he was a part of the powerful Roman army that ended the Second Jewish Revolt (132-135) led by Simon bar Kochba (died 135), after which Jerusalem was renamed Aelia Capitolina and the name of the province changed to Syria Palaestina. Artorius was then stationed in Bostra (Busra ash Sham, Syria). His third centurionate was in the camp of Aquincum in Lower Pannonia (Budapest, Hungry) from 143 to 146. Next, he was in Troesmis, a major military fortress on the Danube, in what is now Romania. Here he became primus pilus—the oldest centurion in the legion— and served as the commander of the First Centuria. He met the requirements to enter the equestrian order and went to Misenium, south of Rome, where he had a command role in the Roman fleet.

The most renowned period of Artorius’ career was when he was assigned to Britain, where he was camp praefectus, second to the camp commander, and was called on to help quell the 155 revolt of the Brigantes, in the north close to Hadrian’s Wall. He probably fought against the Germans in 166 and ended his career as Governor of the province of Liburnia, in what is now Croatia. In Liburnia, Artorius had command of three legions and was given the right to trial and punishment, including the right to execute, a privilege (“the right of a king”) otherwise reserved only for the Emperor. In 174, after 50 years of service, he withdrew to the solitude of his estate in Podstrana, where he apparently died and was entombed.

Was Artorius the real Arthur? His story does not include Merlin, Guinevere, Lancelot, Excalibur or any other of the key people and events of the Arthurian legend as we know it. There are only a few writings from the last years of the Roman Empire in the end of the 4th century and his story is not completely known. Could Artorius’ story have been carried in folk tales carried by wandering troubadours from village to village throughout Europe—smatterings of the tale have been recovered from Italy, France, Germany, Sweden and other places—waiting for Gildas, Geoffrey of Monmouth, Wace and others to put parts of the stories to paper and, ultimately, for Malory to create a book with a comprehensive retelling?

Perhaps Artorius is the Arthur who inspires us to this day.

Perhaps not. In a review of the film King Arthur, Tony Keen, a British “para-academic,” offers a scholarly rebuttal to the idea of Artorius as the real Arthur (9). Keen suggests that a later 5th or 6th century Arthur did exist and that he inspired the stories we know so well.

To add to the confusion, don’t forget Riothamus.

Riothamus was a Romano-British military leader, active at the end of the 5th century, who fought against the Goths in alliance with the declining Roman Empire. The 6th century historian, Jordanes, called him “King of the Britons,” but there is no clear evidence of what he reigned over or who his subjects may have been. Riothamus’ activities in Gaul are reminiscent of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s record of King Arthur’s Gallic campaign. Others suggested that ‘Riothamus’ was not a name but rather a title for Ambrosius Aurelianus, the Arthur-like figure in Gildas’ writing

I don’t care.

Although it was, indeed, a great thrill to stand in the place where the historically documented figure, Artorius, was buried, I can not attest to the complete authenticity of the Artorius-Arthur connection. I am not qualified as an Arthurian scholar to make judgments about the stories but am willing to accept that the exploits of this Roman soldier contributed to the almost two centuries of stories that followed.

However, the Arthur of Camelot that I know evolved mostly from the imaginings of countless authors, men and women, who, in the end, did not consume themselves with finding the unfindable; the complete and ultimate truth of the origin of King Arthur. Those many writers believed in a good and wise and caring leader, a modest man who dreamed of a better world for his people, a man who trusted in magic from a loyal wizard and, mostly, a man who loved the people inhabiting that world, charging them to do noble deeds, to be honest and courageous, and to be guided by his example of infinite love for the world in which he lived.

That is more than enough for me. I will periodically lift a toast to Artorius but will happily continue to believe there was an Arthur and a Camelot. I will continue to see the Lady of the Lake raise the magic sword from the misty sea. I will continue to be inspired by Arthur’s courage and commitment to truth and justice. I will continue to exult in the richness of the Arthur stories as I have read and seen them, the stories that have inspired so many generations.

He is our King. As TH White wrote about in his marvelous adaption of Malory’s story, The Once and Future King.

A haunting statue of King Arthur that now stands at Tintagel

References:

1. He is our King – the life and death of King Arthur over the ages – October 4, 2019 –

He is Our King – the birth and death of King Arthur through the ages

2. Krueger, Roberta. (personal communication; see also: Krueger, Roberta L. (ed). The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Romance. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 2006.

3. Vermaat, Robert M. A new interpretation of the ‘Artognou’ stone, Tintagel. http://www.facesofarthur.org.uk/articles/arthurstone.htm

4. Gwinn, Christopher. Lucius Artorius Castus: A Sourcebook. http://christopherwinn.com/arthuriana/lac-sourcebook/

5. Malcor, Linda A. Lucius Artorius Castus – Part 1: An Officer and an Equestrian. htpps://www.heroicage.org/issues/1/halac.htm

6. Malcor, Linda A. Lucius Artorius Castus – Part 2: The Battles in Britain. htpps://www.heroicage.org/issues/2/ha2lac.htm

7. Turner, Peter. The Real King Arthur: A History of Post-Roman Britannia A.D. 410-A.D. 593 (2 Vol.Set). 1993

8. Cambi, Nenad and Matthews, John (eds). Lucius Artorius Castus and the King Arthur Legend. Split, Knigea Mediteranea, 2014.

9. Keen, Tony. King of the who? http://tonykeen.blogspot.com/2005/02/king-of-who.html

October 20, 2019 at 3:20 pm

Always delightful reading 🙂

October 21, 2019 at 8:48 am

Hi Dr. Geller,

Thanks for this sequel to your other essay on King Arthur. Sounds like a neat place to visit someday!

Amir

October 21, 2019 at 2:49 pm

I was relieved by your last paragraph. At least this mystery surrounding Arthur is not driving you nuts! My exhaustive research in this matter has led me to the conclusion that “Arthur” was Simon bar Kochba, who did not die in 135. He survived and converted to Christianity because he was obsessed with finding the Holy Grail — it would have been heresy for a Jew to find it (and sell it for a pretty penny). So Simon survived through the ages and lived until he was past 2013 years old. He is regaled by Mel Brooks in the accounts of the Two Thousand Year Old Man (and the sequel, The 2013 Year Old Man). And it you don’t believe me, Get Over It. 🙂 It was Simon who hollered, “Get your sticks, get your marshmellows,” and (inadvertently) saved the Hebrew religion. 🙂 🙂

Phil