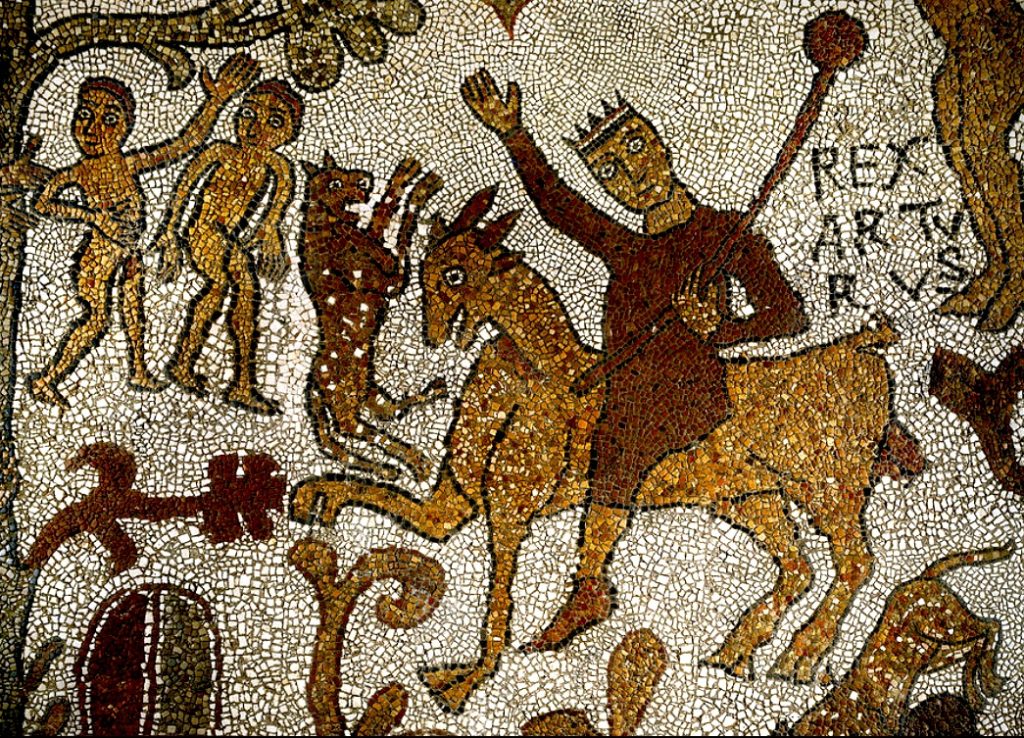

King Arthur (“Rex Arturus”) rides to seek the Holy Grail (11th century) mosaic, Otranto Cathedral, Puglia, Italy

Approximately 20 years ago an Arthurian scholar travelled through Cornwall and Wales, stopping in shops and pubs to try to determine if people still remembered King Arthur. Not infrequently, the response was: “He is our King.”

In every year since 1980 there have been at 4 to 5,000 new retellings of the King Arthur legend, including stories, songs, books, films or comics. Sometime it may be in just in a word or two. As just one example, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, the extraordinarily successful Broadway show, has:

Burr, check what we got

Mister Lafayette, hard rock like Lancelot …

Almost 150 years before Hamilton, in London, Gilbert and Sullivan’s H.M.S. Pinafore also called on the lore of Camelot:

I am the very model of a modern Major-General,

I know our mythic history, King Arthur’s and Sir Caradoc’s …

No one knows exactly how many times the stories of Arthur and his knights, Merlin, Guinevere, and the wonderful tales of courage and honor and chivalry have been repeated since the first writings in the dark ages.

The influence is also apparent in this history of the United Kingdom. In the 6th century, the time most widely accepted as that of Arthur, first-born sons were named Arthur in at least four of the many small kingdoms of England. Henry VII of England had two sons in the 15th century. His first son was 16 when he died, never having assumed the throne; his name was Arthur. The second became Henry VIII, whose daughter, Elizabeth I, oversaw the transformation of England into the dominating country of the world. In our time, Prince Louis Arthur Charles was born to Prince William and Catherine, Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in 2018.

There have been literally hundreds of books about Arthur and his world (appendix 1), dozens of films (appendix 2), operas (e.g. Henry Purcell’s King Arthur, Richard Wagner’s Parsifal, Lohengrin, Tristan und Isolde), popular dramas and musicals (e.g. Camelot, by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe). Arthur and his circle have often been the subject for many artists, particularly the so-called pre-Raphaelites of the

19th century (e.g. Rosetti, Burne-Jones The Last Sleep of Arthur is to the right). Prince Valiant in the Time of King Arthur, a comic strip series originally written and illustrated by Harold Z. Foster, has been published continuously for 82 years and was twice made into a Hollywood film. There are commercial entities in Arthur’s name (e.g. King Arthur Flour, the Excalibur hotel in Las Vegas, Grail Ale, etc). Once or twice a year a New Yorker cartoon will refer to Arthur and his world and Arthurian themes regularly appear in New York Times’ crossword puzzles.

If you “Google” King Arthur you will find more than 524,000,000 citations. Of others associated with Arthur, Merlin has more than 160,000,000 and Guinevere more than 76,000,000. Check the great religious leaders of history; they are looked at less often than Arthur: Jesus Christ has 420,000,000, Muhammad 263,000,000 and Abraham, revered by Jews, Muslims and Christians, 342,000,000. William Shakespeare has only 196,000,000. Winston Churchill 109,000,000. Henry VIII 90,000,000.

Why does this figure from the dark ages, or perhaps before, still resonate so much after all these years? Why is he still an important model for our times?

And what is the story of Arthur?

In fact, there is no single story of Arthur. The saga continues to evolve.

Gildas, a British monk of the 6th century, wrote about an Arthur-like figure, Ambrosius Aurelianus, the son of Romans, who had many of the qualities we associate with Arthur. Five centuries later, Caradoc of Llancarfan wrote The Life of St. Gildas, noting that Gildas was a contemporary of Arthur. Caradoc expands the story and includes the rape of Guinevere by Melvas (? Mordred, the illicit son of Arthur in the legend) but does not mention a Lancelot. In the 8th century, the historian and poet, the Venerable Bede, tells of an Arthur-like figure but, again, never uses that name.

The earliest use of the name Arthur to denote a great hero, used only indirectly in comparison to Gwawrddur, a warrior other than Arthur, is in Y Gododdin, an early Celtic poem from the 6th century:

… pierced more than three hundred of the finest.

He struck at both the center and the flank.

He was worthy in the front of a most generous army.

He gave out gifts from his herd of steeds in the winter.

He fed black ravens on the wall

Of a fortress, though he was not Arthur.

“ … though he was not Arthur.” This, a mention in a poem, is the first documentation of the man we usually think of as King Arthur and is far from hard evidence. As we will see, there is no hard evidence for our King Arthur (but its absence should not keep us from believing).

Geoffrey of Monmouth (~1095-1155) published The History of the Kings of Britain in 1136, a bestseller in its time. Geoffrey’s work collected all of the known Arthur stories and served as the basis for many of the writings to follow. (Geoffrey’s contemporary, William of Newburgh, wrote, in 1190, “ … everything this man wrote about Arthur … was made up, partly by himself and partly by others.”) Geoffrey wrote in classic Latin then Robert Wace (1110-1174) rewrote Geoffrey’s tome in vernacular form, making it more widely available. Wace added the concepts of chivalry and courtly love and provided 642 as the year Arthur died.

Chrétien de Troyes wrote a French text about Arthur in 1181, introducing Lancelot and his romance with Guinevere to the text while repeating Wace’s concept of chaste, courtly love. He also added the Holy Grail quest. In the late 13th century Layaman reworked Geoffrey’s history into English alliterative verse, but altered the ending so that Arthur lived on, after being wounded:

(Arthur) And I will fare to Avalun, to the fairest of maidens,

To Argante the Queen, an elf most fair,

That she shall make my wounds all sound:

Make me whole with healing drafts.

Afterward I shall come again to my kingdom,

And dwell with the Britons with greatest joy.

In 1191, a century before Layaman, a burial site was determined to be that of Arthur and Guinevere. It was discovered in Glastonbury, a small town in Somerset, England. Glastonbury has been inhabited since Neolithic times and has been identified as the ancient site of Avalon, the island of the Arthurian tales first appearing in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History. Geoffrey describes Avalon as the place where King Arthur’s sword Excalibur was forged and, later, where Arthur was taken to recover from his wounds after the great Battle of Camlann.

It is thought that King Henry II, who died two years before the discovery of the Glastonbury tomb, was the impetus for its discovery and either failed to locate it in his lifetime or left notes that led to the burial site’s recognition. Either way, two skeletons were identified in a huge coffin made from a hollowed-out log buried nine feet deep in the ground; the male skeleton was said to be of enormous proportions, fully in keeping with descriptions of Arthur, and the female skeleton was found with a lock of golden hair. The male skull was damaged, as it would be after a fierce battle. There was also a sword in the grave, considered to be Excalibur, and a large engraved plaque, made of stone, or perhaps lead, upon which was carved: Hic jacet sepultus inclitus rex Arturus in insula Avalon (here lies the famous King Arthur on the isle of Avalon) and, on the back, cum Wenneveria uxore sua secunda (with Guinevere, his second wife).

and, on the back, cum Wenneveria uxore sua secunda (with Guinevere, his second wife).

In 1278 the remains were removed in the presence of King Edward I and Queen Eleanor and placed in a black marble tomb in the Glastonbury abbey. In 1519 Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries, the abbey was destroyed and the tomb was lost. Many, however, have suggested that the burial site was fabricated by the abbots who also claimed to have found the burial site of St. Patrick, St. Indract, St. Gildas and St. Dunstan, as well as others who were never in Glastonbury.

Arthur’s story has been written and rewritten countless times over the centuries. The Malory version, described as “the definitive version of the legend,” has also been transformed many times in the half-millennium since it was written and the alterations and additions—relating to Gawain, the Green Knight, Merlin, Mordred and many, many more—are far too numerous to describe in anything less than another book. To appreciate how the Arthur story has evolved over the centuries we can concentrate on the ways in which Arthur’s birth and death have been depicted by comparing just six of the many versions: [(1) 1136; Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain, (2) 1485; Malory’s Morte Darthur [this is the way the title was used in the original version and is the way it would have been spelled in the France of Malory’s time, and not as d’Arthur, the way it is spelled today], (3) 1885; Tennyson’s English Idyls and Idyls of the King, (4) 1958; T.H. White’s The Once and Future King, (5) 1979; Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon, and (6) 1995-97; Bernard Cornwell’s The Warlord Chronicles trilogy, including The Winter King, Enemy of God, and Excalibur]. These six authors span more than 800 years.

Geoffrey tells us that Arthur’s father, Uther Pendragon, falls in love with Igraine (“Igerna”), the wife of another warlord, Gorlois, and “enjoys her by the assistance of Merlin’s magical operations.” Uther, disguised by Merlin as Gorlois, comes to Igraine’s bed and “the same night therefore she conceived the most renowned Arthur.” When Gorlois is killed in battle, Uther marries Igraine. There is no sword in the stone in Geoffrey’s version. Instead, Arthur becomes king when Uther dies: “Arthur was then fifteen years old, but a youth of such unparalleled courage and generosity, joined with that sweetness of temper and innate goodness, as gained him universal love.”

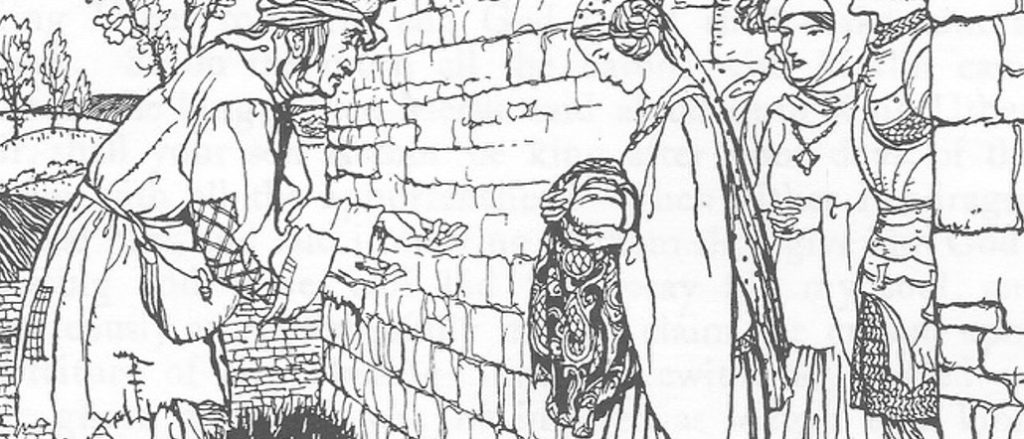

By the time we get to Malory, Merlin is an integral part of the story and he requires very specific compensation for  enabling Uther: “Sir, said Merlin, this is my desire: the first night that ye shall lie by Igraine ye shall get a child with her, and when that is born, that it shall be delivered unto me …” Arthur Racham’s illustration shows the infant Arthur being handed to Merlin. Malory also dramatizes the sword in the stone as the way Arthur became king. Sir Kay, Arthur’s stepbrother (both Arthur and Kay are sons of Sir Ector), loses his sword before a joust. Arthur, Kay’s squire, comes upon Excalibur in a stone, pulls it out, and brings it to Kay. At first, Kay claims to have accomplished the feat himself but soon acknowledges Arthur. This is the story we all know, beautifully depicted in what is arguably the best of all the Arthur films, John Boorman’s 1981 Excalibur.

enabling Uther: “Sir, said Merlin, this is my desire: the first night that ye shall lie by Igraine ye shall get a child with her, and when that is born, that it shall be delivered unto me …” Arthur Racham’s illustration shows the infant Arthur being handed to Merlin. Malory also dramatizes the sword in the stone as the way Arthur became king. Sir Kay, Arthur’s stepbrother (both Arthur and Kay are sons of Sir Ector), loses his sword before a joust. Arthur, Kay’s squire, comes upon Excalibur in a stone, pulls it out, and brings it to Kay. At first, Kay claims to have accomplished the feat himself but soon acknowledges Arthur. This is the story we all know, beautifully depicted in what is arguably the best of all the Arthur films, John Boorman’s 1981 Excalibur.

Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) retells the Malory story, including Merlin’s taking of the infant Arthur, but refers to Sir Anton rather than Sir Ector as stepfather. T. H. White (1906-1964) doesn’t change the details of the birth very much whereas Marion Zimmer Bradley (1930-1999), recounts Arthur’s story from the viewpoint of the women  involved. Bradley writes: “This is ridiculous; even cloaked, Uther looks no more like Gorlois than do I.” Bradley goes on to describe a scene of seduction between Uther and Igraine, approaching rape, but, at the end, notes, “… And this time she let him pull away her gown, and naked, came willingly into his arms.” Bernard Cornwell’s retelling says that Arthur was one of four children born to Uther’s mistress, Igraine, and that Uther selected the great warrior, Arthur, “seemingly a son of nobody,” to be one of the sworn protectors of Uther’s grandson, Mordred, who is to succeed Uther as king.

involved. Bradley writes: “This is ridiculous; even cloaked, Uther looks no more like Gorlois than do I.” Bradley goes on to describe a scene of seduction between Uther and Igraine, approaching rape, but, at the end, notes, “… And this time she let him pull away her gown, and naked, came willingly into his arms.” Bernard Cornwell’s retelling says that Arthur was one of four children born to Uther’s mistress, Igraine, and that Uther selected the great warrior, Arthur, “seemingly a son of nobody,” to be one of the sworn protectors of Uther’s grandson, Mordred, who is to succeed Uther as king.

The various versions of Arthur’s birth, describe him as a 6th C son of Romans living in England, as Uther’s son succeeding his father when King Uther dies, as Uther’s son born to Igraine and taken by Merlin at birth and then succeeding his father upon Uther’s death, as succeeding Uther by pulling the sword from the stone (or, in another variant, pulling the sword from an anvil), and as Uther’s son and brother to Mordred in Cornwell’s series (in which Arthur never becomes king).

In a recently postulated theory, to be discussed in the next blog post (Journey to Podstrana), Arthur is a great 2nd century warrior, born to Roman parents, who battles in many places in the Roman Empire, including Britain, and finally retires to, and dies in, Croatia. This Arthur is never king of all the Britons.

There are just as many variations of the story of Arthur’s death. He is wounded in battle alongside Mordred in 542 (not 642, as Wace indicated), and is carried “to the isle of Avilion to be cured of his wounds …,” giving up his crown to the historically well-documented Constantine (who, after murdering Mordred’s two sons, is then killed by Conan). Malory’s epic has Arthur putting a spear through Mordred (“Traitor, now is the death-day come”) (N.C. Wyeth illustration) as Mordred “smote his father, with his sword … on the side of the head, that the sword pierced the helmet  and the brain-pan … Sir Mordred fell stark dead to the earth and the noble Arthur fell to a swoon in the earth, and there he swooned oftimes.” Malory leaves him in a “swoon” (presumably a coma) but, four chapters later, writes: “Yes some men say in may parts of England that King Arthur is not dead, but had by the will of our Lord Jesu into another place; and men say that he shall come again … But many say that there is written upon his tomb this verse: Hic facet Arthurus, Rex quondam, Rexque futurus (Here lies Arthur, our once and future king).

and the brain-pan … Sir Mordred fell stark dead to the earth and the noble Arthur fell to a swoon in the earth, and there he swooned oftimes.” Malory leaves him in a “swoon” (presumably a coma) but, four chapters later, writes: “Yes some men say in may parts of England that King Arthur is not dead, but had by the will of our Lord Jesu into another place; and men say that he shall come again … But many say that there is written upon his tomb this verse: Hic facet Arthurus, Rex quondam, Rexque futurus (Here lies Arthur, our once and future king).

Tennyson, in the Morte d’Arthur section of Idyls of the King, says,

There came a bark, that blowing forward, bore

King Arthur, like a modern gentleman

Of stateliest port; and all the people cried,

‘Arthur is come again: he cannot die.’

White leaves it to the reader to decide Arthur’s future: “For that time it was his destiny to die or, as some say, to be carried off to Avilion where he could wait for better days.” He finishes the novel cryptically with “Explicit liber regis quondam regisque future the beginning” (The end of the story of the once and future king the beginning).

Cornwell, in the last book of the trilogy, has the squire Derfel watch the boat bearing Arthur recede into the mist; “And so my Lord was gone. And no one has seen him since.”

Bradley’s monumental retelling of the Arthurian legends ends with the dying Arthur held in the arms of Morgaine, his sister and his lover. “And he died, just as the mists rose and the sun shone full over the shores of Avalon.”

Why has the tale of Arthur survived so many centuries and so many iterations? Few works of literature, and few figures in history, have survived as long.

Arthur is the model of honor, of decency and of courage. His Round Table, where all came to contribute and all had an equal place and equal say, is an everlasting symbol of democracy, a pervasive model of ideal government. Ultimately, the Arthur story is about love: love of honor, love of right over wrong, of Arthur’s love for Britain and its people and for his knights, of Arthur’s love for Guinevere and for Lancelot, and also about the love between Lancelot and Guinevere that would destroy the kingdom and blur the Arthur idea. In many tellings the Arthur story is distinctly and emphatically Christian, with the search for the Holy Grail playing a major role. Arthur’s passing is an example of possible resurrection.

T.H. White, in The Once and Future King, wrote that the Arthur story, not least, is about love from a good man: He had been taught by Merlyn to believe that man was perfectible; that he was on the whole more decent than beastly: that good was worth trying: that there was no such thing as original sin. He had been forged as a weapon for the aid of man, on the assumption that men were good … The service for which he had been destined had been against Force, the mental illness of humanity. His Table, his idea of Chivalry, his Holy Grail, his devotion to Justice: had been bred … But the whole structure depended on the first premise: that man was decent.

There is, however, that other, important story with actual physical evidence that leads many to believe in the existence of another Arthur; Lucius Artorius Castus, a 2nd century Roman general. Artorius will be considered in the next blog post, Journey to Podstrana – finding the real Arthur?

Appendix 1 – some favorite novels about King Arthur

Berger, Thomas. Arthur Rex

A distinctly witty retelling. Malory based.

Bradley, Marion Zimmer. The Mists of Avalon

The story of King Arthur from the point of view of three women. A wonderful retelling.

Cornwell, Bernard. The Warlord Chronicles (The Winter King, The Enemy of God, Excalibur)

Arthur is not king, but a valiant soldier. Cornwell’s writing is so vivid you can smell, taste and feel this world as he depicts it.

Lanier, Sidney. The Boy’s King Arthur.

Malory retold specifically for late 19th century boys but easily read by boys and girls.

Malamud, Bernard. The Natural.

A novel about a wound that would not heal, reminiscent of the Fisher King story, with a baseball team called the New York Knights.

Malory, Thomas. Le Morte d’Arthur.

Long and complex, sometimes difficult to follow, sometimes difficult to put down.

Pyle, Howard. The Story of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table.

Malory based. Best known for its wonderful illustrations, also by Pyle (who was admired by many contemporary artists, including Vincent van Gogh). Pyle’s best known book is “The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood,” which he also illustrated.

Steinbeck, John. The Acts of King Arthur and his Noble KnightsThe Nobel Prize winning author of Grapes of Wrath, East of Eden and many more, retells Malory.

Stewart, Mary. The Crystal Cave.

Stewart, Mary. The Last Enchantment.

Stewart, Mary. The Hollow Hills.

Stewart, Mary. The Wicked Day.

Thoughtful and wonderfully written series, with the last book written from the point of view of Mordred in the last years of Arthur’s rule.

Tennyson, Alfred Lord. Idyls of the King.

Poetry at its greatest. The Malory story told anew, but with magnificent emphasis. Hard to read about Arthur’s final battle without becoming sad.

Tolkien, J.R. The Fall of Arthur.

An unfinished poem (abandoned when Tolkien started writing the Hobbit stories, annotated by Tolkien’s son, Christopher). May be of interest to devoted Tolkien readers.

Twain, Mark. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.

An American classic, still wise and witty.

White, T.H.. The Once and Future King.

An outstanding retelling of the Malory story but with much inventiveness. Warm, touching and witty. One of the most wonderful chapters in literature is when Merlin teaches the boy Arthur (“Wart”) to see the world as if he were a falcon.

White, T.H.. The Book of Merlyn.

More highly thoughtful T.H. White, concentrating on the wise magician.

There are countless other creative works about Arthur as well as innumerable texts devoted to the historic and archaeological aspects of the legend.

Appendix 2 – some films based on Arthur and his times.

1949 – A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (Bing Crosby as the Yankee, Rhonda Fleming as his love interest, Cedric Hardwicke as Arthur) (the first sound film of Mark Twain’s novel was in 1931 and starred Will Rogers as the time-traveling Yankee).

1953 – Knights of the Round Table (Robert Taylor as Lancelot, Ava Gardner as Guinevere, Mel Ferrer as Arthur). Dated, but still entertaining in sumptuous Technicolor.

1963 – The Sword in the Stone – a Disney animated version loosely based on T.H. White’s retelling. Terrific for introducing young people to the Arthur legend, but this Arthur is American, not British.

1967 – Camelot – a film adaptation of the 1960 Lerner and Loewe Broadway musical – (Richard Harris as Arthur, Vanessa Redgrave as Guinevere, Franco Nero as Lancelot). The music is marvelous, the performances moving and memorable and, despite the improbability of a musical, the movie works!.

1975 – Monty Python and the Holy Grail – an often slapstick parody, later adapted into a successful Broadway musical called Spamalot. Despite the silliness, the film depicts the medieval time very well, perhaps reflecting Cornwell’s books’ descriptions.

1981 – Excalibur – a film by the great John Boorman, largely based on White’s version of Malory (Nigel Terry IS Arthur, Nicol Williamson IS Merlin, Helen Mirren as Morgana, with Liam Neeson, Gabriel Byrne and Patrick Stewart in notable early roles). A serious, often exhilarating, often sobering, beautiful motion picture. Try not to hold your breath as the sword comes out of the stone. And the scene of Arthur, asking Patrick Stewart, who he has just defeated in battle, to knight him, is marvelous.

1984 – The Natural – based on the Bernard Malamud novel and yes, a baseball film, that deals with redemption and honor and a team named the Knights. The scene with Glenn Close in the bleachers, the sun blazing through her oversize hat as a glorious corona/crown, will stay with you – (Robert Redford, Glenn Close).

1991 – The Fisher King – a complex, dark film, capturing the essence of the Fisher King stories and the wound that will not heal in the modern setting of New York. Marvelous performances by Robin Williams and Jeff Bridges. A powerful, often mesmerizing film.

1995 – First Knight – depicts an abduction of Guinevere by the knight Malagent – (Sean Connery as Arthur, Julia Ormond as Guinevere, Richard Gere as Lancelot). Very warm, very touching, often too sentimental film with Gere not at his best.

2004 – King Arthur – claiming to be based on relatively recent archaeological discoveries, the film garbles the histories of the two most prominent theories about Arthur but does portray him as a Roman soldier and not as a king. A few improbably silly scenes but still worth seeing for the depiction of medieval times, reminiscent of the Monty Python version. Also said to be based on Jack Whyte’s books (which I have not read). This film certainly made me think of Cornwell’s trilogy as well as Artorius of Podstrana (next blog post) – (Clive Owen as Arthur, Keira Knightly as a fierce Guinevere).

Many, many other Arthur motion pictures, most of them dreadful.

Additional references:

Ashe, Geoffrey. The Discovery of King Arthur.

Ashe Geoffrey. King Arthur’s Avalon – the story of Glastonbury.

De Troyes, Chrétien. The Complete Romance.

Geoffrey of Monmouth. History of the Kings of Britain.

Malory, Thomas. Le Morte Darthur.

Mathews, John and Mathews, Caitlin. The Complete King Arthur – Many Forms, One Hero.

October 3, 2019 at 4:24 pm

Fascinating, if a bit overwhelming! You certainly did your research. Very well organized and written as are all your essays.

October 5, 2019 at 10:49 am

Joel,

Thank. Yes, this post was a little too heavy, partly in preparation for the follow-up post which is far less data-driven and, I think, much easier to read.

October 4, 2019 at 1:07 am

“Arthur is the model of honor, of decency and of courage”

If “you know who” could read, He might have been a better President.

October 5, 2019 at 8:23 am

Very informative essay, looking forward to learning about Arturo in your next post!

A couple years ago I read another novel of King Arthur called the Crimson Chalice by Victor Canning. It was a slog to get through and was another origin of Arthur.

https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/victor-canning-2/the-crimson-chalice/

ps I liked the 2004 King Arthur movie as a more realistic version and Clive Owen was well cast in the role.

October 5, 2019 at 10:54 am

Amir,

Thank you for the comments. Happy to hear from you. I did not read the Canning book but will look into it. For me the TH White, Marion Zimmer Bradley and Cornwell books are the best. I also enjoyed the King Arthur movie to a degree, but they tried to blend the 6th century version of Arthur with the 2nd century story of Artorius (the follow-up blog post to come in a week or so), and I found that whole computer-generated ice scene a little too much (I don’t think that is in any of the Arthur stories). My favorite film is still the John Boorman Excalibur; the acting is outstanding, the story is highly plausible (at least if you are an Arthurian, and the music is thrillingly matched to the film details.