My childhood was decidedly unsophisticated in many ways, including gastronomically. For the first decade of my life my parents and I lived with my maternal grandparents, both immigrants from different shtetls close to Vilnius in what is now Lithuania. We lived in the Gowanus neighborhood of Brooklyn, close to its border with Sunset Park, until I was eight years old. It was a blue-collar neighborhood with a mixed population of Italians, Irish and Poles; I was the only Jew in my elementary school. There were very few restaurants nearby; I don’t recall going to any. I didn’t learn about Chinese restaurants or pizza parlors until I was a teenager and we were living in Flatbush. Also, my childhood years were the years of World War II and my family did not have much money. The depression was officially over but that fact may not have yet filtered down to us.

I knew cheese in various forms: cream cheese, cottage cheese, pot cheese and, in a really delicious blintz, farmer’s cheese. You can still get pot cheese and farmer’s cheese in neighborhoods where many Jews live, otherwise it is hard to find. Velveeta was special, almost exotic.

Not everyone knows what a blintz is but there are those who will swear it is the most delicious food they have  ever eaten. It is sometimes referred to as the Jewish crepe. When we lived in Flatbush, the depression and the war over, we sometimes went for Sunday brunch (I don’t think we used that term in those days) at The Famous, a kosher dairy restaurant in Borough Park, a far more Jewish part of Brooklyn, as was Flatbush.

ever eaten. It is sometimes referred to as the Jewish crepe. When we lived in Flatbush, the depression and the war over, we sometimes went for Sunday brunch (I don’t think we used that term in those days) at The Famous, a kosher dairy restaurant in Borough Park, a far more Jewish part of Brooklyn, as was Flatbush.

When I was a medical student in Washington, D.C. I learned about another cheese from cousins who lived across the Potomac and liked to make toasted sandwiches with salami and Gruyère, a hard, slightly salty cheese from Switzerland; I had, of course, never heard of Gruyére but enjoyed eating it. When Kate and I were in the young parent age we attended dinner parties at friends homes where I came to know Brie and Jarlsberg cheeses, both of which were very popular in the early 1970s. Fondue parties were also quite popular at that time, although I always wondered at what seemed to be a silly ritual of dipping a piece of bread into the cheese, eating it, and then waiting for your next chance at the fondue pot. Cheese fondues are classically made with both Gruyère and Emmental, another Swiss cheese.

I first tasted Camembert cheese in late 1979. In London, for only the second time—the first time a few months earlier—I was helping plan the 1980 meeting of the International Society for Preventive Oncology (ISPO). ISPOs President, Herbert E. Neiburgs, was a colleague at Mount Sinai and he asked me to help organize the London meeting (and subsequent—Sao Paolo, Vienna—meetings). Herbert, a pioneering and innovative cytopathologist, was one of the brightest and most interesting people I have known. Erudite, fluent in many languages, and highly cultured, I learned so much from him about politics in the world of science and also about life. After two long days of working on the forthcoming conference, I was free to explore the marvelous city of London (“He who tires of London, tires of life” – Samuel Johnson).

It was a grey, drizzly, chilly typical London November day and I decided to start with the British Museum. I arrived just as a downpour began and I was happy to be inside, although the museum was almost as chilly as the surrounding Bloomsbury neighborhood. Of course, I soon forgot the weather as I wandered through that incredible repository of history and culture. The Rosetta Stone. The Code of Hammurabi. The Gutenberg Bible. The Magna Carta which, I vividly recall, transfixed me for a while as I realized that this piece of parchment, from 1215, signed by King John in the middle of a muddy Runnymede field, established the rule of law and began the path to our own Declaration of Independence and American democracy (unhappily, I wonder if the current oval office occupant knows anything about the Magna Carta and its significance).The Elgin Room is one of the most wonderful places in the world with the scrupulously maintained Parthenon sculptures beautifully displayed.The British Museum overflowed with so many treasures I had read about and now stood mere inches from (in those days the collection was not as protected as it is now). It was intoxicating and exhausting and, after a few hours, I asked a guard to direct me to the cafeteria.

The British Museum now has a bright and shiny, somewhat appealing, easy-to-reach cafeteria as well as a fine dining room. In 1979 the cafeteria was remote and almost impossible to find. A guard directed me to the back of the museum. A door led me out into the rain and down a slippery metal stairway where, in a separate somewhat shabby building, I found a dimly lit, cramped couple of rooms, illuminated by yellowing incandescent bulbs, where food was offered. I was, by then, familiar with scones and tea sandwiches and, instead, decided to try something new, a cheese labelled “Camembert.” I also took a small carafe of (not very tasty) red wine. The Camembert was delicious—more flavorful than Brie, which it resembled—and it remains my favorite, although I now know about Reblochon, Vacherin, Mont d’Ors (if you love very strong cheese, this is the one), Bleu d’Auvergne, St. Aubrey, Pont l’Évêque, Morbier (with that dramatic blue-green line in the middle), and so many other luscious fromages.

Camembert and Roquefort are emblems of France, just as Stilton and Cheddar are for England, and Mozzarella and Gorgonzola are for Italy. There is no reliable data about when cheeses were first used. Roquefort may be two thousand years old or more. Camembert, in contrast, was probably created in the 10thor 11thcentury.

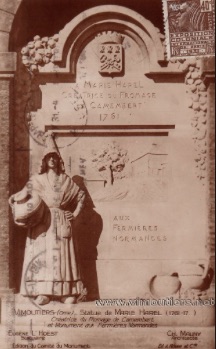

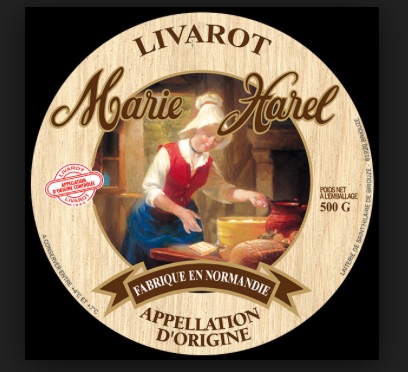

In most discussions of Camembert, however, credit for Camembert’s origin is given to the farmwife Marie Harel (1761-1844). Legend holds that Harel, in or near the Normandy, France, village of Camembert, provided  shelter for a renegade priest, perhaps a cousin or nephew, who, recently sentenced to the guillotine, fled Paris. In gratitude for the shelter Harel provided, the priest taught her how to make the cheese from his local parish, Brie. Brie had been around for more than a thousand years and was quite popular. Instead of preparing it in large wheels she used the smaller shaping molds for making Livarot, another regional cheese (but made from skim, rather than whole, milk). Marie modified the priest’s Brie formula, partly following local cheese making standards, and made a distinctly tasting new cheese: Camembert. In another version of the story, it is said that she made a mistake in her attempt to make Brie, employing the wrong proportion of ingredients.

shelter for a renegade priest, perhaps a cousin or nephew, who, recently sentenced to the guillotine, fled Paris. In gratitude for the shelter Harel provided, the priest taught her how to make the cheese from his local parish, Brie. Brie had been around for more than a thousand years and was quite popular. Instead of preparing it in large wheels she used the smaller shaping molds for making Livarot, another regional cheese (but made from skim, rather than whole, milk). Marie modified the priest’s Brie formula, partly following local cheese making standards, and made a distinctly tasting new cheese: Camembert. In another version of the story, it is said that she made a mistake in her attempt to make Brie, employing the wrong proportion of ingredients.

In any event, Marie Harel is still identified as the person who created Camembert. The cheese historian, Pierre Boissard, credits her fame to the fact that she both founded a cheese making family and also to the fact that she had exceptional commercial sense, and not to inventing a cheese. Her grandson, Cyrille Paynel, evoked his grandmother when he later established the authenticity of Camembert by earning governmental recognition for it.

There are two Napoleonic stories involving Camembert. One, with Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), is almost certainly apocryphal. The one involving Napoleon III (1808-1873) may or may not be true. In the first version, Marie Harel met Napoleon Bonaparte when he visited Normandy. After tasting the cheese, the Emperor proclaimed it the best cheese he had ever eaten and named it after the local village. In the Napoleon III version, the President-turned-Emperor visited Normandy and named it when Paynel presented it to the monarch.

Still, Camembert was not a great success. Camembert’s fame awaited the Industrial Revolution and, importantly, the 1890s invention by a French engineer named Ridel (little else is known about him) of the now familiar wooden box used to transport this soft cheese safely. In the following quarter century Camembert became increasingly identified as a symbol of France. Camembert became internationally known after World War I when French soldiers from regions other than Normandy, as well as those from America, Canada and England, brought the cheese back to their homes.

A later leader of France, Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970), general of the French forces in the second world war, famously, and perhaps bitterly, asked Winston Churchill (1874-1965), “How can anyone govern a nation that has two hundred and forty-six different kinds of cheese?” He did not specifically mention Camembert.

In the 1920s the Camembert industry in Normandy enhanced the story of Marie Harel by erecting a statue of her in Vimoutiers, a local important market town three miles (five kilometers) from Camembert, where she would have sold her cheese. The creation of the statue was, in another story, prompted by the visit to Camembert by a New York physician, Joseph Knirim, who was convinced that eating the cheese (along with Czech Pilsner beer) had cured him of a stomach ailment. The good doctor subsequently successfully treated many patients with the same remedy. Knirim wanted to lay flowers at Marie Harel’s grave but, at the time, no one knew about her or that her remains were in a graveyard in another village, Champosault. Knirin eventually laid a wreath of gilt laurel leaves, adorned with the French and American flags, at the gravesite and left money with the mayor of Vimoutiers to have a statue of Harel created.

It is not known, however, precisely how Knirin would have heard about the origins of Camembert or even how he would have obtained the cheese itself. The medicinal virtues of Camembert (or Pilsner beer, for that matter) were never confirmed. There was, however, another American who became interested in Camembert and who greatly affected the industry.

Charles Thom (1872-1956), a native of Illinois, has been described as “a great scientist and a great man.” He was a microbiologist and mycologist and is known for his pioneering work on the microbiology of dairy products and soil. In particular he carried out pioneering studies on two genera of the fungi Aspergillus and Penicillium, which are integral to making Camembert. As Chief of the Microbiological Laboratory in the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) Department of Chemistry, Thom worked with a number of scientists in developing the standards for food handling and processing in the United

was a microbiologist and mycologist and is known for his pioneering work on the microbiology of dairy products and soil. In particular he carried out pioneering studies on two genera of the fungi Aspergillus and Penicillium, which are integral to making Camembert. As Chief of the Microbiological Laboratory in the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) Department of Chemistry, Thom worked with a number of scientists in developing the standards for food handling and processing in the United  States, particularly in terms of cheeses, working mostly at the Storrs Agricultural laboratories in Storrs, Connecticut. Subsequently he was appointed Chief of the Division of Soil Microbiology. In later years, during World War II, he played an important role in developing production methods for penicillin.

States, particularly in terms of cheeses, working mostly at the Storrs Agricultural laboratories in Storrs, Connecticut. Subsequently he was appointed Chief of the Division of Soil Microbiology. In later years, during World War II, he played an important role in developing production methods for penicillin.

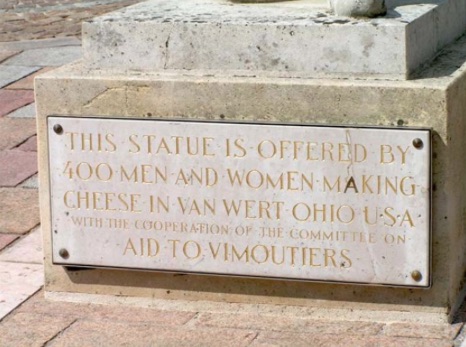

The statue of Marie Harel was damaged, along with parts of the village of Vimoutiers, in June 1944, a week after the Normandy beach invasion (D-Day), as Allied forces accidentally bombed Vimoutiers. In 1953, the statue was replaced and much of the village restored. Both the new statue and the restoration were funded partly by  contributions from employees of the Borden Camembert factory of Van Wert, Ohio. A duplicate of the statue was also made to stand at the factory entrance. In Normandy there are other monuments in her honor, aw well as museum exhibits.

contributions from employees of the Borden Camembert factory of Van Wert, Ohio. A duplicate of the statue was also made to stand at the factory entrance. In Normandy there are other monuments in her honor, aw well as museum exhibits.

Why was the cheese named after the tiny, pretty village of Camembert? Possibly because of one of the two Napoleons? More likely because, unlike the Normandy cheeses Livarot and Pont l’Évêque, Camembert was totally farm-produced and did not leave until it was a fully mature cheese ready the eat whereas the other cheeses matured after leaving the farm.

In 1937, the historian Jean Bard (pen name for Dr. Jean Boulard) demolished the story of Marie Harel and the fame of the village of Camembert itself. He identified a late 18thcentury pamphlet describing Camembert cheese, written before Marie Harel was born. Indeed, Bard indicated there was no evidence she had ever physically been in Camembert village. Inventor or not, there is no doubt Marie Harel produced cheeses in the Camembert fashion and may well have created a new method of production that resulted in what we now recognize as Camembert cheese.

In Marie Harel’s time, Camembert’s outer rind was greenish or greenish-gray. It is thought that this was changed after the time of Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) when people became increasingly aware of bacterial contamination. Modified versions of the cheese, with white rinds, soon became standard. True Normandy Camembert can not be obtained in the United States since federal regulations require that pasteurized milk be used in its manufacture whereas unpasteurized milk is the basis of the best tasting Camembert. In fact, the official AOC (appellation d’origine controlee)designation is only awarded to the cheese made with unpasteurized milk. It bears the label Camembert de Normandie – au lait cru (Camembert of Normandie – from vintage/old-fashioned milk). The milk is ripened by the molds Penicillium candida and Penicillium camemberti for at least three weeks. The only other additives permitted are salt, calcium chloride, yeast and rennet. Before fungi were well understood the cheese color was a matter of chance and often was blue-grey with areas of brown. In the mid-1970s the now familiar white cheese became standard. Camembert de Normandie accounts for only 5% of French Camembert production, the other 95%, generic or hybrid form, is labeled Camembert fabrique en Normandie(Camembert made in Normandy).

In contrast to Brie, which is generally made in wheels 9-15 inches in diameter, Camembert is typically 4 inches in diameter. It is 1 inch thick and weighs approximately 9 ounces. Camembert has less cream than Brie and more active lactic starters, contributing to Camembert’s stronger smell and taste. It is also slightly more yellow  than Brie and tastes earthier, contributed to it being preferred by many cheese lovers. When it is fresh it is quite crumbly and firm but, as it ages, it become increasingly soft and strong flavored.

than Brie and tastes earthier, contributed to it being preferred by many cheese lovers. When it is fresh it is quite crumbly and firm but, as it ages, it become increasingly soft and strong flavored.

Normandy Camembert made from unpasteurized milk is, indeed, uniquely delicious and superior to other Camemberts. Still, many Camemberts made with pasteurized milk are almost as tasty.

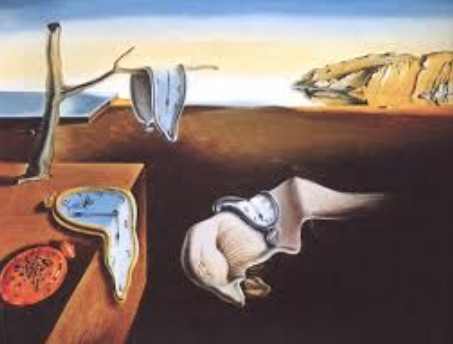

It has been said that a very ripe Camembert, in the runny stage, inspired Salvador Dali to create his great painting, The Persistence of Memory. Dali also wrote: “New York is a gothic Roquefort. San Francisco makes me think of a novel in Camembert.” It is not clear what Dali meant by that.

It has been said that a very ripe Camembert, in the runny stage, inspired Salvador Dali to create his great painting, The Persistence of Memory. Dali also wrote: “New York is a gothic Roquefort. San Francisco makes me think of a novel in Camembert.” It is not clear what Dali meant by that.

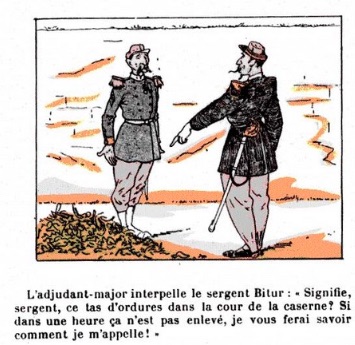

Facéties du Sapeur Camember

A discussion about Camembert cheese has to include at least a mention of the comic  book character who is very popular in France, Sapeur Camember. A sapper is the soldier who does the low-level scut work (e.g., peeling potatoes, washing latrines, building fortifications and digging trenches). The writer Thomas Bass describes him as “illiterate and thick as a plank.” An English version of Facéties du Sapeur Camember might be “The Pratfalls of Private Camember.” He is popular enough to have

book character who is very popular in France, Sapeur Camember. A sapper is the soldier who does the low-level scut work (e.g., peeling potatoes, washing latrines, building fortifications and digging trenches). The writer Thomas Bass describes him as “illiterate and thick as a plank.” An English version of Facéties du Sapeur Camember might be “The Pratfalls of Private Camember.” He is popular enough to have  a statue erected in the village of Lure. There is an fan club you can join and a successful television show was broadcast for some years.

a statue erected in the village of Lure. There is an fan club you can join and a successful television show was broadcast for some years.

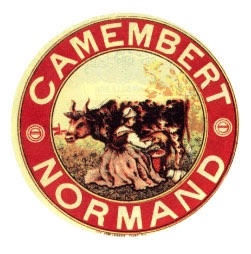

Finally, you can become a tyrosemiophile– a person who collects the round, colorful labels typically affixed to the wooden boxes of Camembert cheese. The earliest labels date to around 1887. The hobby of collecting them was described in the May 1914 issue of the Bulletin de Vieux Papier.Tyro means cheese in Greek, seme stands for sign and phile signifies love or attraction. In 1951 the Societé de Tyrosémiophilie was founded, followed, in 1960, by the Club Tyrosémiophile de l’Quest (Western Tyrosemiophile Club) and then its sister organization, the Club Tyrosémiophile de France, in 1969. The labels can often be found at flea markets or in antique stores, and have included illustrations of Normandie cows, dairymaids and shepherds, and, of course,  Marie Harel, who also appears on the box labels of other Normandie cheeses, such as the Livarot shown to the right below.

Marie Harel, who also appears on the box labels of other Normandie cheeses, such as the Livarot shown to the right below.

The launch of Sputnik was depicted on other boxes of Camembert, as was the Le Mans car race, Mother Goose, the three blind mice, King Kong holding a camembert box, even a nude, partially covered by the name of the producer, Fromince. The development of the labels may have been a way to competitively respond to the growing export market faced by hundreds of Camembert producers in the early twentieth century. The Club Tyrosémiophile de France maintains a quarterly bulletin and holds meetings in which members compare and exchange labels. Alas, unaware of the hobby, I have discarded many labels.

References:

Boisard, Pierre (tr. by Richard Miller): Camembert – a national myth. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1992.

Bouchait, Dominique. Fromages: An Expert’s guide to French Cheese. New York, Rizzoli, 2019

Donnelly, Catherine (ed). The Oxford Companion to Cheese. New York, Oxford University Press, 2016.

Harbutt, Juliet. World Cheese Book. London, DK, 2009.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Les_Facéties_du_sapeur_Camember

http://club-tyrosemiophile.com

http://club-tyrosemiophile.fr/actus

August 9, 2019 at 4:53 pm

I don’t have any “cheesy ” comments.To lower serum cholesterol, cheese is off most health diets. If you know off acceptable cheese on a low cholesterol diet, this would be great information.

August 10, 2019 at 4:25 pm

Statins work well.

August 9, 2019 at 4:55 pm

Dr. Geller, thank you for the informative, well-written essay! Amir

August 10, 2019 at 4:25 pm

Thank you.

August 10, 2019 at 3:54 pm

Excellent scholarly treatise on Fromage.. Try Epoisses also. the cheese

mite “tyroglyphus’ may account for some cheese allergies or itch.

Morbier is my “go-to” cheese of choice

August 15, 2019 at 2:45 pm

Thanks,it is nteresting, enlightening, well written, pleasant to read. Simply enjoyed.

Jan S

August 16, 2019 at 10:41 am

Steve, I love reading your blogs. They are entertaining and very informative- please keep up the great work.

Mark R

September 1, 2019 at 4:24 pm

When I was a pathology resident at Mt Sinai, I expanded my food knowledge with periodic visits to a marvellous cheese shop on Lexington Avenue between 85th and 86th. I was a revelation to me having grown up with Kraft American Cheese and Safeway cottage cheese. I think the shop had hundreds of varieties of cheeses from around the world. Fortunately they had free samples.