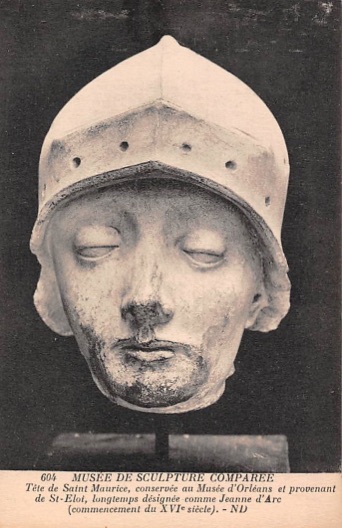

This may well be the actual face of Joan of Arc. From contemporary reports, she was 5 feet 2–3 inches tall, athletic, and had dark brown  hair and a somewhat short neck. We have no detailed description of her face, including her eye color, but we do have many accounts of men saying she was attractive, even beautiful, although others did not share this view. This helmeted head of a late Gothic saint’s statue wasis considered to have been modeled after the real Joan, mostly because it was carved at the time she lived. There is no absolute proof of this really being the face of Joan. In contrast, there is a sketch made in 1529, that is considered to have actually

hair and a somewhat short neck. We have no detailed description of her face, including her eye color, but we do have many accounts of men saying she was attractive, even beautiful, although others did not share this view. This helmeted head of a late Gothic saint’s statue wasis considered to have been modeled after the real Joan, mostly because it was carved at the time she lived. There is no absolute proof of this really being the face of Joan. In contrast, there is a sketch made in 1529, that is considered to have actually  been drawn by Clément-de-Gauguembergue as Joan rode by.

been drawn by Clément-de-Gauguembergue as Joan rode by.

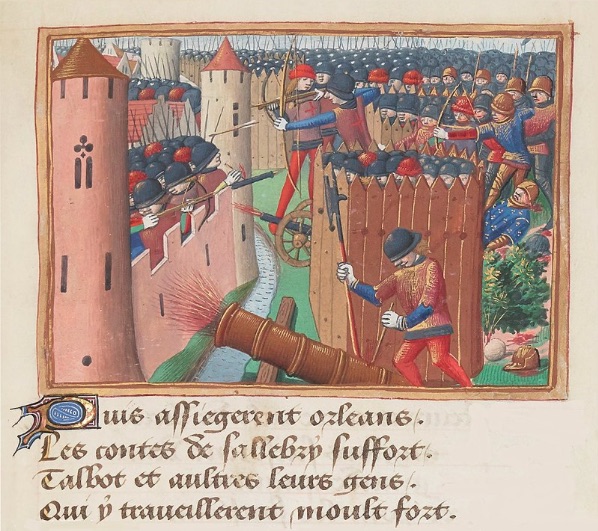

There have been many, many artistic representations of Joan including (from the left) a 15th C rendering of the siege of Orléans where her early success over the English led to her wide-spread acceptance as the savior of France, an idealized portrait by the great artist Ingres, a 20th C illustration in the newspaper Figaro by Lynch depicting her holding a sword and the representation of Joan at the stake, painted by Herman Stilke.

If you have been to Paris you have almost certainly have seen the glistening gold statue of her on horseback that is behind the Louvre.

behind the Louvre.

I don’t recall exactly when I first became fascinated by the story of Joan of Arc (~1412-1431), Jeanne d’Arc in French or, as she called herself,  Jehanne la Pucelle (“Joan the Maid”). Joan was an actual living person and, although she was likely not literate, this is her signature.

Jehanne la Pucelle (“Joan the Maid”). Joan was an actual living person and, although she was likely not literate, this is her signature.

The first time I went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art was on a class trip from my Brooklyn junior high school. This was 1950 to 1952 and I had been to the Brooklyn Museum but not The Met. My parents were not museumgoers and I left The Met thinking about two magnificent oil paintings. The Horse Fair, painted by Rosa Bonheur in 1852, a 2.4 x 5.1 meter oil painting, was so vivid I was sure I could taste the dirt raised by the onrush of magnificent steeds at the mid-19th-century Paris horse market. More impressive for me, however, was the 1879 Jules Bastien-Lepage Joan of Arc, also quite large, at 2.5 x 2.8 meters, which depicts the

teenage Joan in her parents’ garden, with three saints—Michael, Margaret and Catherine—barely seen in the trees behind her. The expression on her face, the wonderment in her eyes, forever captured me and I never fail to stop to see this magnificent painting when I visit The Met, at least two or three times each year.

teenage Joan in her parents’ garden, with three saints—Michael, Margaret and Catherine—barely seen in the trees behind her. The expression on her face, the wonderment in her eyes, forever captured me and I never fail to stop to see this magnificent painting when I visit The Met, at least two or three times each year.

Recently, I watched, for the first time, the 1928 French silent film, La Passion de Jeanne

d’Arc (The Passion of Saint Joan). The film, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer (1889-1968),

d’Arc (The Passion of Saint Joan). The film, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer (1889-1968),  starred Renée Jeanne Falconetti (1892-1946) as Joan (in her career Falconetti was also credited as Maria Falconetti, Marie Falconetti, Renée Maria Falconetti or, simply, Falconetti). Falconetti’s Joan is even more transfixing than the Joan in the painting.

starred Renée Jeanne Falconetti (1892-1946) as Joan (in her career Falconetti was also credited as Maria Falconetti, Marie Falconetti, Renée Maria Falconetti or, simply, Falconetti). Falconetti’s Joan is even more transfixing than the Joan in the painting.

I have known about this motion picture for a long time but, somehow, never before managed to see it. The Passion … is regarded as a landmark in the history of cinema and Falconetti’s performance has long been considered one of the finest ever filmed.

What a mistake in not seeing it before! This film is remarkable. Beautiful. Unforgettable. Magnificent cinematography. Exceptional sets. Brilliant direction but, above all, Falconetti’s performance is, indeed, extraordinary. Mesmerizing. Almost supernatural. (https://archive.org/details/DreyersThePassionOfJoanOfArc)

A reviewer said “perhaps the finest of all silent movies: beautifully acted, inspired photography, new score magnificent.” (The only quarrel I have with this is the background musical score, added long after the film was made. I found it obtrusive at worst and otherwise banal. When I lowered the sound, the film was far more enjoyable).

Seeing this extraordinary silent movie made me think about my long-time fondness for Jeanne d’Arc.

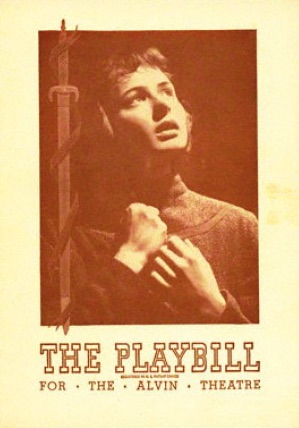

Approximately five years after first seeing that Bastien-Lepage painting at the Met, I saw the George Bernard Shaw play, Saint Joan, at the long gone, legendary, Phoenix Theater in Greenwich Village, New York. It was early 1957, I was not yet 18 years old and a sophomore student at Brooklyn College, undecided about my future and taking courses mostly in English and History. Friends invited me to go with them to see the show. The off-Broadway production was standing room only and, indeed, we stood. It starred  Siobhann McKenna (1923-1986), one of the greatest actors of the Irish stage. Her performance was widely praised as the greatest rendition of the role ever seen. She, McKenna-Joan, was captivating, thrilling, inspirational. This remains the most memorable live theater experience I have experienced.

Siobhann McKenna (1923-1986), one of the greatest actors of the Irish stage. Her performance was widely praised as the greatest rendition of the role ever seen. She, McKenna-Joan, was captivating, thrilling, inspirational. This remains the most memorable live theater experience I have experienced.

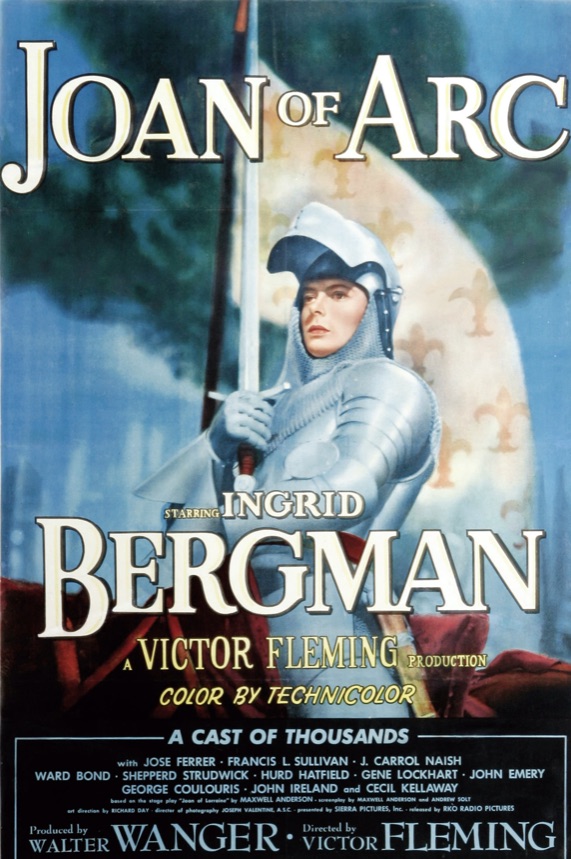

In 1948, Ingrid Bergman (1915-1982) starred in Joan of Arc, a film directed by Victor Fleming (1889-1949) who, in the one year 1939, had directed both The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind. The Bergman film was based on the highly praised Broadway show, Joan of Lorraine, by Maxwell Anderson (1888-1959), from two years earlier, in which she also starred. Bergman received one of the first Tony awards for her stage performance.

Wind. The Bergman film was based on the highly praised Broadway show, Joan of Lorraine, by Maxwell Anderson (1888-1959), from two years earlier, in which she also starred. Bergman received one of the first Tony awards for her stage performance.

Joan of Lorraine is a play-within-a-play. It tells of a company of actors  staging a dramatization of the story of Joan of Arc and, especially, is about the effect the story has on them. Most of the actors play two or more roles, and, in the stage production, Bergman played both Joan and Mary Grey, the fictional actress who, in the dramatization, plays Joan. Mary Grey and the fictional director are in conflict about how the role should be played. The conflict, with the Mary Grey character insisting—both in her own words and also the words she speaks in the Joan role—that Joan can not tolerate corruption of her divine mission, is resolved during the course of the play.

staging a dramatization of the story of Joan of Arc and, especially, is about the effect the story has on them. Most of the actors play two or more roles, and, in the stage production, Bergman played both Joan and Mary Grey, the fictional actress who, in the dramatization, plays Joan. Mary Grey and the fictional director are in conflict about how the role should be played. The conflict, with the Mary Grey character insisting—both in her own words and also the words she speaks in the Joan role—that Joan can not tolerate corruption of her divine mission, is resolved during the course of the play.

The Bergman film that was made from Anderson’s play discards the play-within-a-play construct and concentrates on the story of Joan of Arc. Bergman’s outstanding performance earned an Academy Award nomination, one of seven she received (For Whom the Bell Tolls, The Bells of St. Mary’s, Joan of Arc, Autumn Sonata, Gaslight, Anastasia, Murder on the Orient Express). She won the Oscar for each of her last three nominations but, interestingly, did not even get nominated for portraying Ilsa Lund in Casablanca, which is often considered her most memorable part. The film of Anderson’s play is excellent and worth seeing, if only for Bergman’s vivid and heart-breaking performance.

construct and concentrates on the story of Joan of Arc. Bergman’s outstanding performance earned an Academy Award nomination, one of seven she received (For Whom the Bell Tolls, The Bells of St. Mary’s, Joan of Arc, Autumn Sonata, Gaslight, Anastasia, Murder on the Orient Express). She won the Oscar for each of her last three nominations but, interestingly, did not even get nominated for portraying Ilsa Lund in Casablanca, which is often considered her most memorable part. The film of Anderson’s play is excellent and worth seeing, if only for Bergman’s vivid and heart-breaking performance.

Thirty years before Maxwell Anderson wrote Joan of Lorraine, George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), the brilliant Nobel laureate Irish playwright, critic, musicologist, polemicist and political activist, whose rapier wit skewered many, wrote Saint Joan, the play that so memorably introduced me to Joan of Arc.

Thirty years before Maxwell Anderson wrote Joan of Lorraine, George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), the brilliant Nobel laureate Irish playwright, critic, musicologist, polemicist and political activist, whose rapier wit skewered many, wrote Saint Joan, the play that so memorably introduced me to Joan of Arc.

Anderson’s Joan of Lorraine is sometimes ponderously serious with only rare, brief flashes of humor. In contrast, Saint Joan is full of (often sarcastic) wit. The play itself is approximately 120 pages long in the Penguin edition and is preceded by a 65 page highly erudite, often mocking, preface which contains 41 subsections, many having tantalizing headings, such as “Joan the Original and Presumptuous,” “Joan and Socrates,” “Was Joan Suicidal?” “Catholicism not yet Catholic Enough,” “Joan as a Theocrat,” “The Real Joan not Marvelous enough for Us,” “Some Well-meant Proposals for the Improvement of the Play,” and, lastly, “To the Critics, lest they should feel Ignored.” At the very beginning, Shaw notes, “As her actual condition was pure upstart, there were only two opinions about her. One that she was miraculous; the other that she was unbearable.” This sardonic description is hardly the one we usually hear about Joan. And, later in the preface: “Joan was burnt without a hand lifter on her own side to save her. The comrades she had led to victory and the enemies she had disgraced and defeated, the French king she had crowned and the English king whose crown she had kicked into the Loire, were equally glad to be rid of her.” Shaw was, in many ways, a feminist long before anyone imagined the term and the preface is a delight to read for that, and many more, reasons. It also includes a very thoughtfully written, succinct history of the real Joan.

There was a film version of Shaw’s play, Saint Joan, scripted by the great writer, Graham Greene, and directed by  one of Hollywood’s finest director’s, Otto Preminger. Preminger carried out a nation-wide search for an unknown actress to play Joan. This was the premier movie performance for the

one of Hollywood’s finest director’s, Otto Preminger. Preminger carried out a nation-wide search for an unknown actress to play Joan. This was the premier movie performance for the  Iowa schoolgirl Jean Seberg; unfortunately, both she and the film were panned. After a couple of unsuccessful performances Seberg moved to France and became one of the leading French New Wave actresses, achieving great success in Breathless, starring with Jean-Paul Belmondo, as well as in number of films for which she received excellent reviews; François Truffaut called her “the best actress in Europe.” Her performance in the Warren Beatty film, Lilith, led to a reappraisal of her career and her being acknowledged as an accomplished and serious actress.

Iowa schoolgirl Jean Seberg; unfortunately, both she and the film were panned. After a couple of unsuccessful performances Seberg moved to France and became one of the leading French New Wave actresses, achieving great success in Breathless, starring with Jean-Paul Belmondo, as well as in number of films for which she received excellent reviews; François Truffaut called her “the best actress in Europe.” Her performance in the Warren Beatty film, Lilith, led to a reappraisal of her career and her being acknowledged as an accomplished and serious actress.

But Seberg was a heroic, and tragic, figure beyond her acting career. She, like Joan, fought hard for her beliefs. She was conspicuously active in the 1960s in support of civil rights including being involved with dissident groups such as the Black Panther Party. Her life story became eerily reminiscent of that of Joan of Arc when she became the object of persecution by her own country, the United States government. The FBI carried out a major program to discredit and publicly harass her, including stalking her, break-ins of her home, highly defamatory (and determined, in the courts, to be libelous) statements to the public and press, enlisting the aid of the CIA, the Secret Service and U.S. Military intelligence. J. Edgar Hoover, Richard Nixon and other officials participated actively in measures to destroy her reputation and career. When her artistic reputation was restored, she was blacklisted. Her personal tragedy includes serious psychiatric problems and possible suicide, although many close to her said that was not likely (ten days after disappearing, her decomposing body was found wrapped in a blanket in the seat of her car parked close to her Paris apartment with an empty barbiturate bottle and a suicide note to her son. However, her former husband, Romain Gary, thought she had been murdered.). A current film, Seberg, starring Kristin Stewart, is about this part of her life.

There have been many films about Joan, including at least a half dozen called Joan of Arc and a number called Saint Joan. A French 2017 heavy-metal retelling of the story, Jeannette: The childhood of Joan of Arc, is about her formative years. That film’s director, Bruno Dumont, released a second, dramatic version in 2019, not yet available with subtitles. Belladonna of Sadness is an erotic Japanese film telling Joan’s story. In 1954, six years after making the film with Victor Fleming, Ingrid Bergman played Joan in an Italian version directed by the Italian director, Roberto Rossellini, whose adulterous relationship with, and eventual marriage to, Bergman led to her own Seberg-like experience. Bergman was condemned by the Catholic church (even though she was not a Catholic) and, in the McCarthy era, denounced on the floor of the U.S. Senate [in those years, probably akin to a badge of honor]. She had her own period of blacklisting, including being banned from The Ed Sullivan Show, a particularly successful television show of the time. To his credit, Steve Allen immediately invited her to appear on the Tonight show and commented on “the danger of trying to judge artistic activity through the prism of one’s personal life.”

The George Bernard Shaw play also led to one of the better Joan movies, a 1967 American film made for television starring Geneviève Bujold. Of the many films, I have not seen the heavy metal version, and most of the other Joan films have been mediocre, at best. Joan of Arc also appears as a character in Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, another cinematic adventure I have not experienced. An interesting film, albeit not successful, is The Miracle of the Bells, starring Fred MacMurray, Valli (Alida Valli who was so luminous in the great film The Third Man), Lee J. Cobb and an over-his-head Frank Sinatra, early in his acting career. The movie was written by the novelist and playwright Ben Hecht and the renowned journalist Quentin Reynolds. Olga, a young woman from a coal-town, is asked to replace a temperamental actress in a film being made about Joan of Arc. Olga dies before completing the film, ostensibly from tuberculosis contracted because she lived in a coal community. Valli makes the film almost worth seeing.

to replace a temperamental actress in a film being made about Joan of Arc. Olga dies before completing the film, ostensibly from tuberculosis contracted because she lived in a coal community. Valli makes the film almost worth seeing.

Twenty-eight years before the Dreyer-Falconetti silent movie, Georges Méliès (1861-1938), filmed his own version of the story of Joan of Arc. Méliès, perhaps the most influential creative force in the earliest days of cinema, made A Trip to the Moon in 1902, the film which made him famous and which was featured in the magical 2011 Martin Scorsese film, Hugo. The 1900 Joan of Arc silent, partly colorized film (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vBXSratgqVk) is only 10 minutes long but is more than worth the time.

is only 10 minutes long but is more than worth the time.

Why is Joan so important for me?

We all come to know many heroic and legendary figures in our childhood years. By the time I got to college, my list was quite long: Robin Hood, King Arthur, Eleanor Roosevelt, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, General MacArthur (at least until his ego became so publicly dominant), Jackie Robinson, Duke Snider, Pee Wee Reese, Shane, Atticus Finch, Jefferson, Einstein, Lincoln, Beethoven, Clarence Darrow, d’Artagnan and more. None of these, other than MacArthur, has ever lost my high regard.

But Joan was different. She exemplifies unswerving commitment to and confidence in her beliefs. Courage, Loyalty, Unshakeable faith (although I certainly don’t now, and never did, share her beliefs and have never accepted that there really were voices for her to hear or Saints to see; I have no trust in the mysteries of religion).

It is not what she believed that stirred my admiration, but how she believed. The intensity of that belief that allowed her to lead an army, defeat an enemy and crown a king, is what captured me. It is not so much the source of the light, but the intensity. When I stand before the Bastien-Lepage painting, as I will likely do in the next few months, and stare at the look in Joan’s eyes it will be to affirm my belief in the heroic life of the girl herself, rather than her voices and visions.

A few recommendations: See the 1928 Dreyer silent film, The Passion of Saint Joan. It is more than worth your time because of the marvelous cinematography and the superb direction, but mostly because of the extraordinary, haunting and memorable performance by Renée Jeanne Falconetti. See the Ingrid Bergman film directed by Victor Fleming; another magnificent performance by one of the great 20th century actors. Visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art and stand before the Bastien-Lepage painting – concentrate on the look of trust, of pure, simple, limitless adoration, of faith, captured in Joan’s eyes. If you are lucky enough to happen upon a revival performance of Shaw’s Saint Joan, don’t pass it by. If not, read the play – you will very much enjoy it!

March 15, 2020 at 12:13 am

Stephen,thanks so much; I learned a lot, and now am eager to see your film recommendations. By the way, I agree with you about MacArthur.

March 15, 2020 at 7:58 am

thank you, once more, Steve…..

please do keep your experiences and thoughts and suggestions coming—they are a treasure, and remind me of how little i knew/ know about a long-time, good friend. i am incredibly impressed with your your memory and your manner of presentation. my lack of curiosity is distressing and i hope to improve with the stimulus you provide.

love, milt

March 15, 2020 at 8:33 am

Fascinating what captures our imagination and how it stays with us forever. My father was a jazz musician and the magic of that community is with me always. And the 1950’s dodgers.

March 15, 2020 at 4:03 pm

Great way to spend our time in relative isolation. Reading and trying to see these movies.

Great writing and this present virus lack of human contact gives us an opportunity to write and read, expanding our knowledge and entertaining our venue starved needs.

March 16, 2020 at 8:32 am

Dr. Geller,

Excellent essay as always! I love the blend of history and art.

One more portrayal of Joan of Arc that I remember watching as a child- a comedic version – was in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure from 1989. The movie’s Ted was the breakthrough role for Keanu Reeves. I decided to look up who played the role of Joan of Arc. Her name was Jane Wiedlin and she was actually was a founding member of the Go-Gos!

March 16, 2020 at 12:16 pm

Dear Friend, Your article was very informative and interesting.;however when I read the title I hoped you were referring to me. At this age I could use a little passion.

Fondly, Joan (Stevens)

March 16, 2020 at 4:07 pm

Thank you, Dr. Geller, for this new release. Captivating reading, as usual.

Thank you for sharing your experiences of life, letting us know a little more from you beyond your immeasurable medical skills.

March 16, 2020 at 4:08 pm

Thank you, Dr. Geller, for sharing this new release. Captivating reading, as usual.

Thank you for sharing your experiences of life, letting us know a little more from you beyond your immeasurable medical skills.