The Obi-Wan Machine

a short story

Stephen A. Geller

Nobody knows Ira Bissel.

Bill Gates doesn’t know Ira. Warren Buffet doesn’t know Ira. J. Edgar Hoover, were he alive and still busily running around the FBI in a dress, wouldn’t know Ira.

Ira Bissel is a decidedly self-effacing seventy-year-old man, modest in stature and demeanor. A shade less than sixty-five inches tall, now an inch less than when he was young, he’s always been a slightly chubby 175 pounds despite almost daily exercise for the last ten years. A few wispy strands of gray long ago stopped covering the top of his head, while a full garland of hair, recently more white than gray and badly in need of trimming, sits over the back of his head from ear to ear. His short-trimmed, salt-and-pepper beard and mustache are mostly salt. Rimless glasses, generally in need of cleaning, with smeared fingerprints holding on to dandruff flakes, periodically slip down on his nose. His usual outfit is a pair of tan, well-wrinkled pants and a very worn and scruffy high school sweatshirt. He no longer gives much thought to how he looks since Ruthie, who died more than two years ago, isn’t there to encourage him to look his best.

Although he’s accepted that she’s gone, he still expects her to pat the back of his head where he once had a cowlick.

Ira is very calm, very thoughtful, very mild-mannered.

Ira is also very rich.

Ira is determined to make the world––the whole world––a better place before he dies.

A pioneer developer of semiconductors and then microchips, Ira was wealthy before he was twenty-five. After his thirtieth birthday, he asked Ruthie, his childhood sweetheart, then pregnant with the first of their three children, if she would oversee their money so he could devote himself to inventing.

One mild September evening when they were sitting on the back patio after dinner, and after working with three reasonably capable financial advisors in as many years, Ruthie said, “Ira, just give me one year to do it all by myself. If we don’t make money in that time, I’ll find some bright young person just out of Wharton or someplace like that and turn it over to him or her.” She emphasized “her” and, pausing briefly, added, “Let me give it a try.”

Without hesitation, Ira clapped his hands and said, “Yes! Terrific.”

Ruthie resigned her position as a law school librarian to prepare for the baby, but also to spend many hours with their tax lawyer, their accountant, and her Barnard roommate, who taught economics at Yale. The train rides to and from New Haven were devoted to reading about economics, investing, world markets, accounting, and more.

One lazy afternoon, a heavy rain outside, when Ira and their one- month-old little girl, Amy, were napping, Ruthie pulled out a pad of long, yellow legal paper and prepared three columns: “invest,” “maybe,” and “definitely not.” At the top of the page, she wrote in red crayon, “No companies we don’t like,” and underlined it three times.

Tobacco was “definitely not.” Firearms manufacturers were “definitely not.” Las Vegas hotels were “definitely not.” In the days of apartheid, South Africa was “definitely not.” Soon after Mandela was released from prison––and it was clear he would be the next president––she bought a small, struggling South Africa mining company that was bankrupt. She actually bought the company’s entire vegetation-poor mountain, known as “Onvugbaar.” Anticipating a Mandela-era increase in tourism, she planned to develop a resort on the sixty-two acres. The inspector they hired said it wouldn’t take much to clear the land––it was mostly dirt and rock with sparse vegetation––and they could start building anytime.

Onvugbaar brings in well over a hundred million dollars each year after the highly improbable discovery of diamonds on one side of the mountain and extremely rich veins of gold on the other. Dozens of geologists explained why that couldn’t happen, while Ruthie counted the seemingly endless supply of money that never stopped flowing from Onvugbaar. Each month, when she reviewed the company’s earnings statements, her shoulders would hunch down a little and she would look side to side, even though she was alone, like a little girl with her momma’s lipstick smeared on her face. In a Rosebud-like whisper, she’d murmur, “Onvugbaar,” which she learned, to her great amusement, is Afrikaans for “barren.”

Ruthie selected all their investments, all the real estate, all the businesses, everything they had around the world. Buying and sell- ing small companies whenever she wanted, she almost always turned them into successes and, also almost always, made them grow. If she didn’t like a prospective company’s logo, it would go in her “depends” column, but more often than not, she thought of it as a “definitely not.” She once explained her reason to Ira: “The logo speaks to judg- ment, how the leadership thinks.” She almost sold their Pepsi stock when the company came out with the red, white, and blue globe logo. “It’ll take more than a wishy-washy design to top Coke,” she wrote to the chairman of the board. If a company used a rap star in a commercial she wouldn’t invest in it. “With Sinatra, Judy Garland, Crosby, you could understand what they were singing, for goodness sake.”

A few months before she got sick and died, Ruthie invested in GlassSings, a struggling Chicago-based seven-employee company. The founder and CEO, Paul Morson, earned his Ph.D. studying ways to get glass to conduct electricity without using embedded wires. He was struggling to create a marketable product.

At about the same time, she found a Boston-based, equally small, equally struggling, similarly experimental plastics company. PlasGlo’s CEO, Paul Frankel, earned his degree studying the light-transmitting properties of various polymers. He could no longer support his five employees and was completing the bankruptcy papers when Ruthie showed up at his door by accident. She intended to invest money in a tiny cupcake shop across the street from PlasGlo. The cupcake business was run by three young women, all of whom had a disability.

She talked for two hours with Frankel. He showed her his pro- totypes for new kinds of plastic lenses controllable by smartphones or smartwatches. His creations could change color or magnify and project images. Before leaving she leaned toward him, as if sharing a confidence, and said, “I’m not sure I understand much of what you told me, but I am impressed. And I admire your enthusiasm. Expect a call from Ira.”

Twenty minutes later, she bought a 25 percent interest in the cupcake place, reasonably sure she wasn’t going to make much money there. But the cupcakes were delicious and she bought a dozen to take home.

Ira said he couldn’t remember which Paul did what––although, of course, he could––and he collectively referred to them as “glass and plastic.”

Ira didn’t like having partners, and four months after Ruthie’s funeral, he bought the companies of both Pauls outright, keeping the two developers in charge while increasing their salaries and giving them highly favorable stock options. Except for installing a single communications system to unite the two entities, he didn’t make any other major changes. He also bought the cupcake store, created similarly generous arrangements for the original three owners, and moved the store to the mall at the Pru Center, where it did quite well.

Ira also bought a rubble-filled block in south Brooklyn, a few blocks from the water. He built a two story brick building on two-thirds of the property so he could “tinker” as often and as efficiently as possible. Two stories of usable space underground included a spacious twenty-car garage in case he decided to collect automobiles. The structure was mostly laboratories in which he installed the most sophisticated equipment and electronics backed up with the most pow- erful computers and servers, including two superconductors almost as powerful as a Cray and as fast as Watson. He learned about integrated circuits, computer imaging, nanotechnology, robotics, image analysis, photovoltaic glass, fluid dynamics, and much more.

On the remaining one-third of the land, he had a community park built and made sure it was kept scrupulously clean. He called it “Ben Blue Park” in memory of a high school chemistry teacher who once inspired him. For months after Ruthie’s death, he spent weekends at their Chappaqua home––Ruthie bought it before the Clintons moved there––but increasingly, Ira stayed in Brooklyn so he could work in the labs day or night or both. The small apartment overlooked the playground. An eighteen-foot-long copper bas-relief plaque had an Andrew Carnegie quote: “To try to make the world in some way better than you found it is a noble motive in life.” He was particularly happy when he saw children carefully reading it.

No one except his own children and his attorneys and accountants knew exactly how much money Ira had since Ruthie had used so many identities, other than Ira’s name, for their companies. He never appeared on the lists of richest people.

All three children were professionals. Amy, the oldest, was a pediatric oncologist specializing in childhood lymphomas. Michael, the middle child, was a successful novelist who taught at Dartmouth. Ron, the youngest, had a Ph.D. in astrophysics from MIT and was one of the lead scientists on the Mars project. The children were required to make their own way in the world, although they would eventually have a sizable inheritance even after most of Ira’s money went to a variety of organizations around the world: schools, hospitals, museums, symphony orchestras, and more.

Ira loved Paris and they planned to live there a few months each year. Ruthie bought one more Paris apartment, this time not for investment but as a place for them to live in. They purchased first-class tickets on Air France. Six weeks before the planned trip, Ruthie experienced severe, persistent back pain and underwent resection of a pancreatic cancer. A half year after, she died. Ira never went to Paris again.

While Ruthie was in the hospital, Ira saw much he was sure he could make better. He asked Glass and Plastic to improve the screens of the monitors tracking blood pressure and other vital signs. He developed a robotic device to help move obese patients. He created an inexpensive heating sac to safely warm blood before transfusions.

And more.

A day before Ruthie died, Ira’s friend Phil Butler sent him the video of some British broadcaster railing about the “Islamization of Europe” when there was a plan to build a mosque close to the site of the London Olympics village. Butler attached clippings about a couple of suicide bombers, about a young man trying to detonate an explosive device at a Thanksgiving rally in Oregon, about the outcry against building a mosque near “ground zero,” and about a newly passed Oklahoma law outlawing Islamic law in Oklahoma courts, even though no one had ever tried to use Islamic law in Oklahoma. Whole articles about the Boston Marathon bombing. Charlie Hedbo. Brussels. San Bernardino. In the email’s subject line, Phil wrote “epidemic delusional activity.” And he added, “Ruthie will hate all this, won’t she?”

Two weeks later, after the funeral, after sitting shiva and writing thank-you notes, Ira video-called Glass and Plastics. It was past midnight.

“Hey, how are you guys doing?”

The two Pauls each mumbled a few sleepy words of greeting and nodded at Ira.

Ira chewed on his lower lip a few seconds, raised his eyebrows, bushier than ever since Ruthie’s illness kept her from trimming them, and furrowed his forehead. He cleared his throat twice and, as a slight grin replaced what the Pauls thought had been a grimace, said, “When’s the last time you guys read the Koran?”

***

It took more than ten months of long days and many weekends–– almost every weekend until the Pauls’ wives complained directly to Ira––to create the device. To figure out how to quickly manufacture the hundreds of thousands––maybe millions––needed. How to deliver them. Ira found key collaborators to plot out logistics, to predict weather patterns, to identify launch sites. To understand tribal issues, customs, dialects, terrain, clothing. He made dozens of trips to big cities and small cities around the world, to villages, busy crossroads. He talked with priests and ministers, imams, rabbis, lay leaders of churches, mosques, temples. He toured factories and farms. He met with professors and students.

As they got closer to the end of the project, he repeatedly said, “Perfect is our minimal requirement.”

One day, Ira and the two Pauls were having lunch in a small conference room. Glass Paul, a gangly six-foot-two scarecrow of a man with horn-rimmed glasses and a Prince Valiant haircut, stopped chewing, even though his mouth was full of tuna fish salad. He jumped to his feet and waved his bottle of water at Plastics and, eyes wide and almost bulging, fixed his stare at Ira. Food still in his mouth, mayonnaise and tomato seeds dripping down his chin, he whispered, “Ira, you’re going to get the Nobel Peace Prize for this.”

Plastics, almost as tall as Glass, but with a crew cut to match his military bearing, exclaimed, “Dammit, Paul, you are so right. I should have thought of that. Ira, you are going to change the world. The Nobel Prize.” He paused, a tear forming at each lid, and raised his own bottle in toast. “Ira, we will never be able to thank you enough for letting us share in this project. To go on this journey. Never.”

Ira’s head tilted as he looked up at them, frowns alternating with smiles as he composed his thoughts, wishing he had a floppy hat to swat at each of them. “Sit down, you crazy guys. You’re making me blush.” He leaned toward them, his voice a little lower. “Look, I really appreciate the thought and the words and, mostly, the feelings behind what you just said. We have really gotten close through this, and I agree that––if it works––it will be a monumental achievement. But,” now he spoke more forcefully, emphasizing almost every word, “there isn’t going to be any Nobel Prize or MacArthur Prize or Stanley Cup or whatever. Not even a Cracker Jack prize. No one is going to know about what we’ve done. Not now. Not for a hundred years. Maybe not ever, but definitely not for at least a hundred years.” He paused. “And if it works––I don’t mean the technology, that is going to work, you guys have created something beyond amazing––but if we really change minds, change hearts, we need to let it set in for a long, long, long time.”

The Pauls stood and clinked their bottles together, saying softly and in unison, “To Ira.”

Ira waved both hands toward them. “Listen, if anyone discovers that a crazy old Jewish man from Brooklyn was involved in this nutty scheme, we’ve wasted our time. The whole thing will be doomed to failure.” He let them think for a moment. “People have been taught to hate for hundreds and hundreds of years. Thousands. A century may not be long enough to keep the secret.” A big grin captured his face. “Besides, George Lucas really began the whole thing.”

When they first started working together, the Pauls whispered about Ira as a “possible crackpot.” Their next designation, “weirdo,” quickly changed to “interesting guy,” to “clever,” to “brilliant,” and then “visionary.” Recently “mystic” and “mythic” crept into the lexi- con, and now their rapt, unblinking gazes seemed to say “saintly.”

“Look,” Ira took a few steps toward the door, “we need to stop this mishegas and get back to work. There’s still a ton of stuff to do. Isn’t the aeronautical guy coming this afternoon? We need to get our message safely on the ground, you know.”

The recordings were prepared all over the world. Hundreds of men––and a few dozen women chosen for select sites––read similar sections of the Koran or the Torah, the New Testament, the Bhagavad Gita and the Ramayana, the Tipitaka, the Kojiki, and many others.

Most refused any compensation, guaranteeing confidentiality with a handshake, a bow, or a reverential salute. Glass took a photo of an almost seven-foot-tall Masai chief, who had a literature degree from the Sorbonne, bending over to kiss Ira on the top of his head.

The programming, the insertion of data, took place in Brooklyn with Ira insisting they check it a dozen times to make sure there were no mistakes. They identified the very few dates on the calendar that didn’t coincide with a religious or national event.

When what Glass and Plastic called “Ira’s D-Day” arrived, almost all of the weather predictions proved accurate. Rain came in the expected places. Across the world, drones no larger than a tea saucer–– slightly less than two million drones in all––took off from various islands, ranches, farms, private landing strips, and other properties–– an empty tract of land in Finland, Nahaleg Island in the Red Sea, a deserted village in Ethiopia, specially built wooden ramps floating offshore from Madagascar or Sri Lanka, Jakarta––all strategically purchased or leased or borrowed. A retired Air Force brigadier general, son of Afghani immigrants, was in charge of the launch. “You’re our Eisenhower,” Ira told him more than once. They flew from dozens of uninhabited islands, farms, valleys, and mountain caves in every part of the globe.

As night crawled across the earth, the special messages went out. At the precise moment the rising sun pierced the horizon, the drones descended to exactly fifteen feet and dropped hundreds or even thousands of tiny less-than-feather-weight mixed composition glass and plastic T-shaped wafer-like flakes, their color precisely matched to the terrain to which they were assigned. Molecular nanomotors whirred quieter than could be heard as they transformed the wafers into tiny cubes, invisible in the dirt or the sand or the village street, impervious to feet or hooves, wagons or cars or trucks.

Exactly at noon, the cube produced a pinhole beam that instantly created an awe-inspiring life-size hologram of a holy man, easily recognizable as an imam, a priest, a rabbi, a prophet, a shaman. The figure spoke to quickly gathering crowds of men and women and children, so many of whom had never seen television, let alone a hologram. The words were about Abraham or Moses or Mohammed or Jesus or Buddha, about loving all mankind, pursuing knowledge and truth, foregoing hate and violence, embracing peace. About the end of killing.

In less than a minute, the light shrank back to pinpoint and the figure was gone in an almost invisible puff of smoke as a minuscule embedded charge noiselessly exploded.

Hundreds of millions soon chanted or prayed or sang about stopping all hostility, all hate, all violence, all killing.

Before the end of the next day, countless flaming pyres, in villages around the world, were ablaze with discarded pistols, rifles, grenades, and ammunition.

Soldiers by the millions abandoned their arms.

By evening, the world was quiet, was at peace.

Jews and Arabs embraced in the Golan, at the Allenby Bridge. Satellites captured lines of ragged soldiers leaving Afghani caves and Yemeni villages, guns strewn about. In Tehran, the Supreme Leader asked for the release of all prisoners. ISIS flags lay everywhere. Police departments in every city found their station doors clogged with abandoned weapons.

Newspapers and television broadcasts throughout the world all carried the same one word headline: Peace.

***

It wasn’t any one thing that went wrong.

A woman wearing a black chador and driving a red Jaguar dropped her cell phone while driving on a street in Neuilly-sur-Seine, losing control of the car, which jumped the curb and killed a young Jewish woman and her three children. It didn’t matter that the driver was heading home after an interdenominational meeting at the local synagogue where a peace celebrating party was being planned. It also didn’t matter that the young woman killed was returning from an afternoon tea with her best friend, an Irani Moslem, where they discussed organizing a support group for refugees. At almost the same time, a young Palestinian man in a Jerusalem cemetery mourned the anniversary of his wife’s death––she had undergone chemotherapy at Hadassah Hospital––as an Israeli soldier stopped to light a cigarette, resting his rifle atop a gravestone. This prompted the mourner to scream, “Sacrilege,” and attack the soldier with the trowel he brought to tend his wife’s grave’s flowers. The soldier shot and killed him. In Madrid, a teenage boy wanted to board a bus to relinquish his supply of explosives at the main police station, but panicked when a policeman asked what he was carrying; the boy ran and was shot in the back, shot in the duffel bag, causing an explosion that killed him and maimed dozens of bystanders. Other occurrences in almost every country were reported. In Brussels, an émigré Iraqi dentist recognized a man as one of his torturers when he was in a London prison in the months following 9/11; the dentist fatally stabbed the CIA agent who was passing as an oil engineer. In the midst of a brutal heat wave, a farmer whose crop had failed in the drought ran into his bank and shot and killed a teller, a bank guard, and three customers. The headline on the New York Post front page said: “Terror in the Heartland—Is It ISIS?” even though the farmer was a Boise-born Baptist who served in the first Gulf War and was being treated for post-traumatic stress disorder.

A month later there was no evidence anywhere that the world was changed. No one talked about the miracle. Gun and ammunition manufacturers rejoiced at the unexpected boom in sales.

The stock market was as bullish as ever. Ira spent more than two billion dollars on what they eventually called the Obi-Wan project, but six months later, he was as wealthy as ever.

Ira summoned the Pauls and their wives and his own family to meet in Omaha.

“Ruthie would not have liked the name of this restaurant.” Ira smiled as he cut into his steak. “She would tell us, more than once, that ‘Modern Love’ is not a good name for a fine dining place. She would tell the manager. I can almost hear her say ‘What kind of cockamamie name is that for a restaurant?’ just before suggesting we buy the place.” He pushed a forkful of food into his mouth and slowly and carefully chewed it before sipping his Pomerol. “But the food is luscious, isn’t it?”

“Mom would have loved the place, once we managed to get her past the name,” Michael said. He held his glass up, “To Ruthie.” The din of the restaurant faded as their glasses clicked––a few people at nearby tables turned to watch, and a waiter deboning a trout looked up––and, in unison, they repeated, “To Ruthie.”

Then Ira cleared his throat, coughed twice, put his knife and fork on the edge of his plate, and tapped his wineglass with the handle of a knife to get everyone’s attention. “I wanted you all to come here and spend a little time with me so we can start to figure out what we need to do the next time. What went wrong? How do we make it work?”

The Obi-Wan Machine

Stephen A. Geller

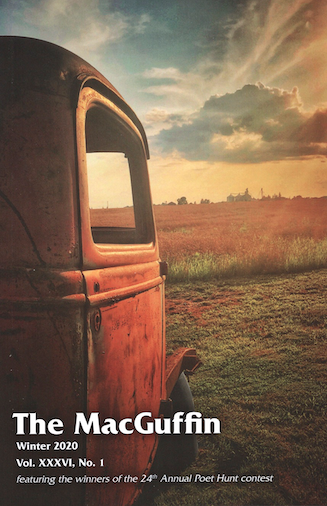

The MacGuffin

Vol. XXXVI, No. 1

Winter 2020

April 5, 2020 at 8:44 pm

An intriguing foray into sociopolitical Sci-fi!

April 5, 2020 at 10:19 pm

what was the interval?

April 6, 2020 at 8:08 pm

A good story and message.

April 6, 2020 at 8:09 pm

A good story and message. It seemed like non-fictional at first…..wouldn’t it be great if it were?

April 8, 2020 at 5:10 pm

Captivating! Loved the humorous style, the characters, the intruigue, the message….

August 6, 2020 at 10:36 am

I’m biased but it’s a very interesting and fascinating read. It must be our DNA 😇