The Second Robert Remak

Students of mathematics and crossword puzzle aficionados may be familiar with the name of the brilliant 20th century mathematician Robert Erich Remak (1888-1942) who is remembered for his pivotal 1911 work (“the Remak  decomposition”) in the somewhat arcane discipline of group theory. Described as a “brilliant algebraist and number-theorist” and “a leading scholar in the splendid and important field of geometry of numbers,” his work is critical to the understanding of what is now called the Krull-Remak-Schmidt theorem; an important mathematical theorem that is far beyond my ability to explain and might well challenge the ability of most readers to understand.

decomposition”) in the somewhat arcane discipline of group theory. Described as a “brilliant algebraist and number-theorist” and “a leading scholar in the splendid and important field of geometry of numbers,” his work is critical to the understanding of what is now called the Krull-Remak-Schmidt theorem; an important mathematical theorem that is far beyond my ability to explain and might well challenge the ability of most readers to understand.

Remak translated mathematical concepts into theories of economics and his 1929 essay, “Can economics become an exact science?” is a cornerstone in the understanding of socialist and capitalistic economies. He also anticipated the role played by digital computers in numerical solutions of systems of linear equations.

On November 9, 1938, Kristallnacht—the night of broken glass when Nazis attacked Jewish businesses, synagogues and homes in Germany’s major cities with the death of more than one hundred Jews—Remak was arrested by the  Gestapo and sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Because of the tireless efforts of his non-Jewish wife he was released after a few weeks and allowed to go to Amsterdam. However, he was again arrested four years later by German occupation forces in the Netherlands in 1942 and transported to Auschwitz, where he was murdered. Dozens of mathematicians and scientists, as well as writers, artists, musicians, legal scholars and others were also victims of the rampant anti-semitism carried out by the Nazis.

Gestapo and sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Because of the tireless efforts of his non-Jewish wife he was released after a few weeks and allowed to go to Amsterdam. However, he was again arrested four years later by German occupation forces in the Netherlands in 1942 and transported to Auschwitz, where he was murdered. Dozens of mathematicians and scientists, as well as writers, artists, musicians, legal scholars and others were also victims of the rampant anti-semitism carried out by the Nazis.

A plaque in his memory can be found in the streets of modern day Berlin.

Ernst Remak – father and son of a Robert Remak

The mathematician Remak’s father was the distinguished neurologist Ernst Julius Remak (1849-1911).

Ernst Remak, son to one Robert and father to another, was educated at the most important German universities of his time. He obtained the M.D. degree in 1870. At Heidelberg, he was a student of the renowned neurologist Wilhelm Heinrich Erb (1840-1921) who, with the brilliant Polish physician Samuel Goldflam (1852-1932), described myasthenia gravis, a neuromuscular disorder that leads to progressive muscle weakness and fatigue, and is sometimes associated with tumors of the thymus gland.

The first Robert Remak

The first Robert Remak (1815-1865), grandfather of the 20th century mathematician, was a renowned neurologist, microscopist and embryologist. He studied with Johannes Müller (1801-1865), pioneer in the understanding of the structure of the cell, and Johann Schönlein (1793-1864), a brilliant physician best remembered for his recognition of what was eventually called Henoch-Schönlein syndrome, an immune inflammatory disorder that affects small blood vessels and occurs mostly in children.

The first Robert Remak (1815-1865), grandfather of the 20th century mathematician, was a renowned neurologist, microscopist and embryologist. He studied with Johannes Müller (1801-1865), pioneer in the understanding of the structure of the cell, and Johann Schönlein (1793-1864), a brilliant physician best remembered for his recognition of what was eventually called Henoch-Schönlein syndrome, an immune inflammatory disorder that affects small blood vessels and occurs mostly in children.

Born in Poznan, Poland (Posen, in German), he graduated from medical school at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in 1838, and worked as assistant lecturer for Müller. Because there was no salary associated with the position, he was forced to maintain an active clinical practice which drew him away from his scientific endeavors. Despite this, Remak made a number of important and lasting observations, including, and particularly, the recognition that cells derive from the division of other cells, contradicting the free cell formation concept of Theodor Schwann (1810-1882). Remak’s observations directly provided the basis for the cell theory of Rudolf Virchow (veer-kov) (1821-1902). Virchow’s proposal—omni cellulae e cellulae (all cells come from a cell)—is considered one of the most important concepts in the history of medicine overthrowing centuries of misbelief in a variety of factors (humors, black bile, etc.) thought to be the basis of disease. The cell theory was vital in the development of modern medicine.

In sharp contrast to Virchow’s wrongly held view that cancer cells developed in unorganized mucoid substance from a pluripotential connective tissue corpuscles, Remak identified the epithelial origin of carcinomas. In a series of papers he emphasized the essential difference between epithelial and mesodermic tumors.

Remak discovered the nerve fibers to the heart, referred to as Remak ganglia. He described non-myelinated nerve fibers and also demonstrated the connection between peripheral nerve cells and fibers. He was one of the first to describe the pathology of tertiary syphilis involving the sensory tracts of the spinal cord (“tabes dorsalis”) and the pathology of ascending neuritis. Robert Remak was also an early advocate of electrotherapy (“shock therapy”) for neuropsychiatric disorders.

In 1855 Remak completed an extensive five-year study of embryology. He provided microscopic evidence for the three distinct germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and entoderm) and was able to trace the derivatives of those layers in the chick embryo. In this treatise he also documented his observations of cells forming in the embryo by division, concluding the book with an extensive discussion of the evidence for cell division as the principal and, in his view, only way for new cells to develop. This was the work that, in the view of many scholars, Virchow plagiarized.

The first Robert Remak was only 50 years old when he died, most likely from sepsis. He was highly susceptible to infections since he had diabetes mellitus in an era long before the time when insulin therapy was developed.

Question #1: why is this gifted, innovative and highly productive physician-scientist almost completely unknown today?

Remak’s arguments for the division of animal cells as the starting point for new cells and also for abnormal cells were poorly received. The very same concept of cell division as the key factor in the understanding of diseases did not achieve acceptance until forcefully promoted by Virchow years later.

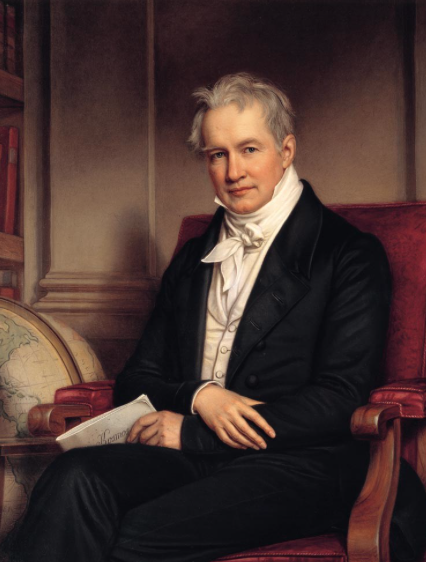

Remak was repeatedly denied a full university professorship. His university appointments came relatively late in his  career and were unaccompanied by either salary or laboratory space. It required the assistance of Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859). The Prussian polymath, naturalist, geographer, explorer of the Americas, scientist and philosopher, intervened, on Remak’s behalf, with the Prussian king who, in turn, granted minimal support but allowed for Remak’s academic advancement.

career and were unaccompanied by either salary or laboratory space. It required the assistance of Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859). The Prussian polymath, naturalist, geographer, explorer of the Americas, scientist and philosopher, intervened, on Remak’s behalf, with the Prussian king who, in turn, granted minimal support but allowed for Remak’s academic advancement.

Question #2: why were the efforts of Humboldt—whose work was acknowledged as highly influential by Darwin, Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Emerson, and countless others—needed for Remak to gain (belated and inadequate) recognition of his extraordinary body of work?

Answers: Robert Remak was a Jew who refused to forsake his religion in a time when being Jewish was a liability in the academic and scientific world. His seminal work was denied by his contemporaries and was not acknowledged by Virchow or his successors.

In contrast to Robert Remak, as just one example, the younger Moritz Cohn (1837-1902), at the University of Vienna, was a Jew who converted to Catholicism and changed his name from Cohn to Kaposi. He was then able to marry the daughter of the great pioneering dermatologist, Ferdinand Ritter von Hebra. Kaposi become a Professor and, ultimately, succeeded Hebra as chairman of the department.

Today’s blog messages:

- Diminishing humans to consider their ethnicity before anything else can deprive us of their individual achievements and potential contributions to mankind. It is highly likely that major contributions could have been made from the Remaks of both the 19th and 20th century.

- The dramatic rise in anti-semitism throughout the world and in the United States needs to be addressed. This is not an ancient event that recurs now and then but, instead, is more virulent than ever. In 2018, more than 4 million anti-semitic tweets were shared or re-shared (https://www.adl.org/audit2018).

- The ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement is important and should not be obscured by semantic games (e.g. ‘all lives matter’) designed to obscure its importance. Although it is encouraging to see how mixed the crowds protesting again continuing bigotry have been, there remain deep roots to the anti-Black tree.

- Don’t forget the first Robert Remak.

July 10, 2020 at 10:18 pm

Another fascinating intellectual tour de force!

Your posts always provide stimulating reading.

July 11, 2020 at 12:20 am

Your blog expresses what many of us wish we could. It should not matter what color you are, what religion you choose (or don’t choose), where you were born or lived, who your relatives were or where or if you went to school, it only matters what you do with any talent that you possess.

Keep on expressing.

July 11, 2020 at 1:28 am

I continue to be surprised both by your depth and tenacity! I am honoured to call you my friend.

July 11, 2020 at 10:42 am

Note also the connection with Erb’s palsy.

July 11, 2020 at 10:57 am

astonishing manuscript. Reading your paper is delicious and runs fluent, pleasurable. I am pleased to know you and learn important topics of Medicine and its history. This manuscript is very contemporary and addresses rememberings for loose minds. Thanks Dr Geller.

July 14, 2020 at 11:51 am

Your blog is a treasure. So called ‘trivia’ that reads as if one is starting a novel, comes with historical perspective, plus political, social and medical information. Love it and can’t wait for Vertigo!

August 2, 2020 at 8:29 am

Dr. Geller, great essay! Educational with a message. Amir