If you are of a certain age the word ‘vertigo’ may bring to mind images of a terrified Jimmy Stewart and the luminous Kim Novak.

Perhaps the Golden Gate Bridge will also crowd into your memory, as will the name ‘Hitchcock.’ The film “Vertigo” was not a great success when it was first distributed and did  not garner recognition at awards time. In the last decade, however, critics have begun referring to this movie as, at least, one of Alfred Hitchcock’s best with some unequivocally calling it his masterpiece.

not garner recognition at awards time. In the last decade, however, critics have begun referring to this movie as, at least, one of Alfred Hitchcock’s best with some unequivocally calling it his masterpiece.

Recently, I experienced unexplained vertigo, the medical condition, not the film, for the first time and learned a great many interesting things from the experience.

Vertigo has been recognized since antiquity. This is not that surprising since so many afflictions of mankind have been described in the writings of Hippocrates of Kos (460 – 375 BCE) and others of his time. Hippocrates described what seems to be vertigo as the “presage of disaster,” likely associating it with some developing circulatory event such as stroke or developing heart failure. Julius Caesar (101-44 BCE) is considered to have been epileptic but some scholars are convinced he actually suffered from vertigo. Archigenes (end of 1st C-beginning of 2nd) probably also described vertigo. Juvenal, the poet (1st C) described alcohol-induced vertigo as “… the roof spins around dizzy, the table dances, and every light is double.” Aretaeus of Cappadocia (2nd C), second to Hippocrates in renown, wrote: “If darkness possess the eyes, and if the head be whirled about with dizziness, and the ears ring as from the sound of rivers rolling along with a great noise, or like the wind when it roars among the sails … we call the affection ‘scotoma’ or ‘vertigo;’ a bad complaint indeed …”

In the 10th century, the great Persian physician and polymath Avicenna (980-1037) provided the most detailed account of vertigo ever written, attributing the disorder to a long list of unnatural causes, each having its own symptom (a symptom is something the patient experiences and is able to relate to the physician and a sign is an objective finding the physician can observe). Avicenna recommended specific therapy, details of which are not clear.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) lived a relatively short life, yet his erudition and the depth and breadth of his knowledge are remarkable and mysterious. He did not have a university education but seemingly knew almost everything. (Some still claim it wasn’t Shakespeare who wrote those great works but no one else has been unequivocally identified as the author and, generally, it’s not that important an issue, except for scholars). In his plays we find history, geography, religion, the law, and the various sciences, including medicine.

In 1603, approximately fifty years after Eustachio (~1500-1574) described the anatomy of the auditory canal of the

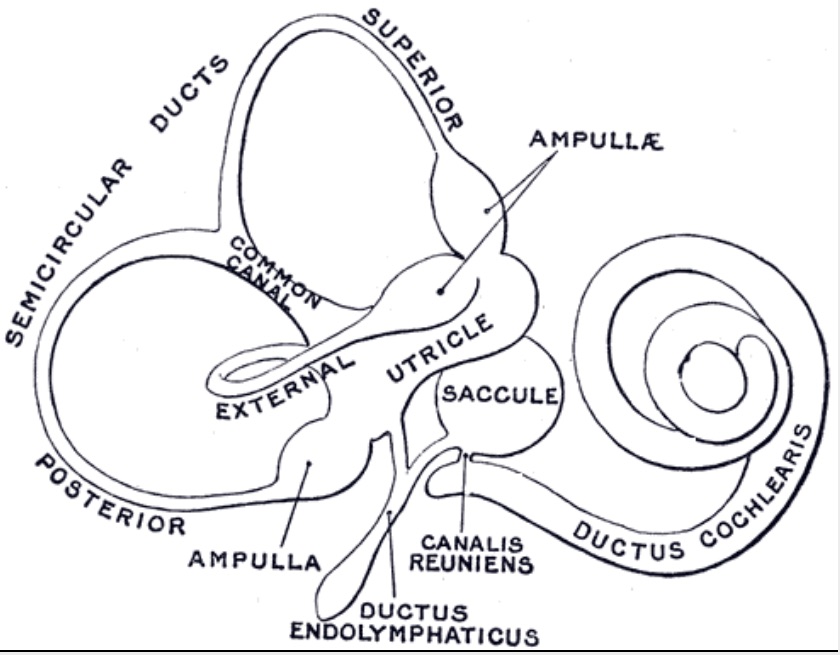

ear, Shakespeare told, in Hamlet, of murder by instilling poison in what is now called the Eustachian canal. In a related anatomic discovery, Eustachio’s contemporary, Fallopio (1523-1562), who described the uterine tube that still bears his name, was the first to describe the semicircular canals (semicircular ducts) of the ear, the site for origin of most vertigo cases. Although Shakespeare does not comment on the canals themselves, it would seem that he speaks about vertigo in Act I, Scene II of Romeo and Juliet, when Benvolio says

ear, Shakespeare told, in Hamlet, of murder by instilling poison in what is now called the Eustachian canal. In a related anatomic discovery, Eustachio’s contemporary, Fallopio (1523-1562), who described the uterine tube that still bears his name, was the first to describe the semicircular canals (semicircular ducts) of the ear, the site for origin of most vertigo cases. Although Shakespeare does not comment on the canals themselves, it would seem that he speaks about vertigo in Act I, Scene II of Romeo and Juliet, when Benvolio says

Turn giddy, and be holp by backward turning

(translation expressly developed for this essay: If you have vertigo you’ll helped by changing the orientation of your semi-circular canals).

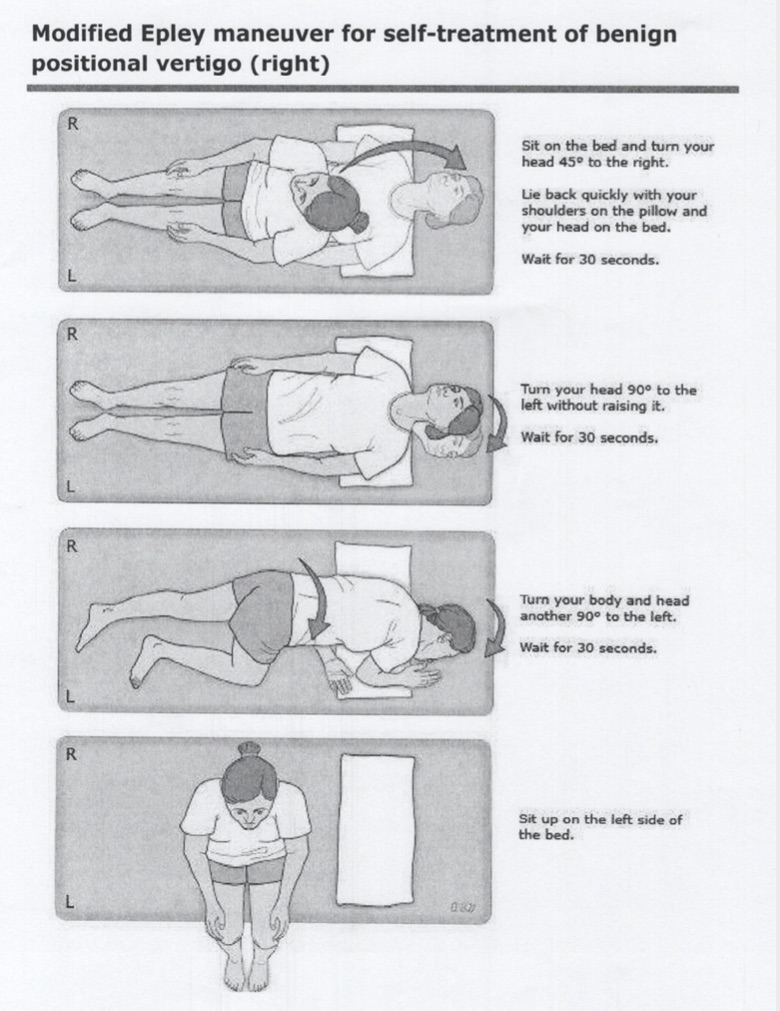

As we will see a particularly effective therapy for the most common form of vertigo is ‘backward turning:’ changing position to briefly re-orient each of the three semicircular canals. This method, credited to the distinguished 20th C otorhinolarungologist, John Epley, rather than Benvolio, can be quite successful.

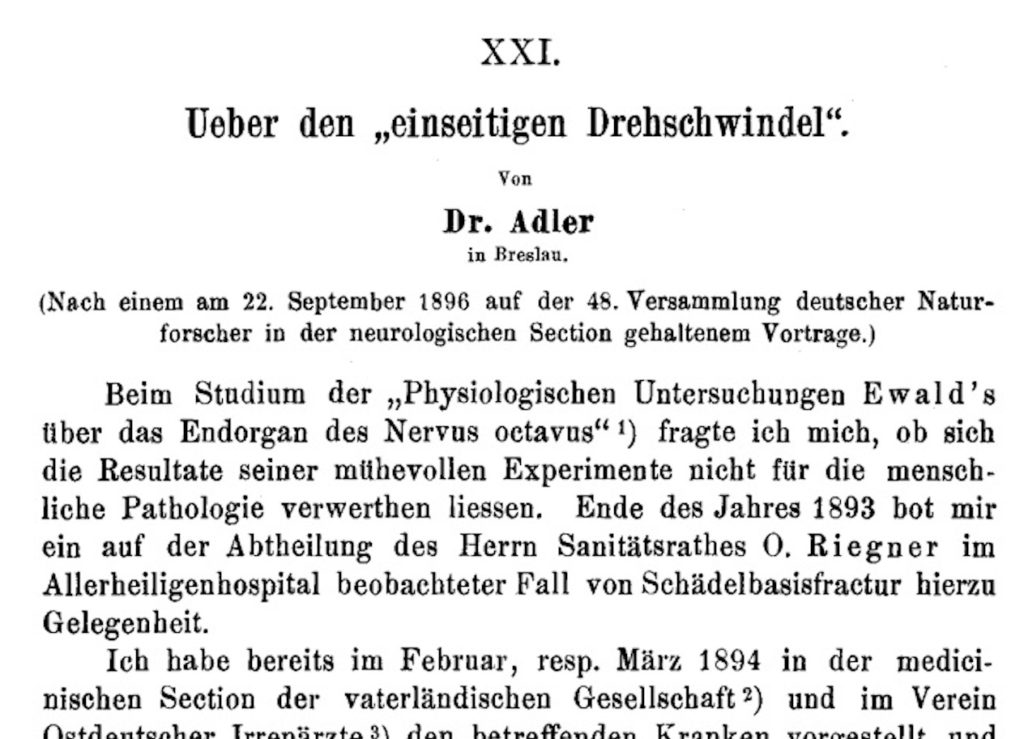

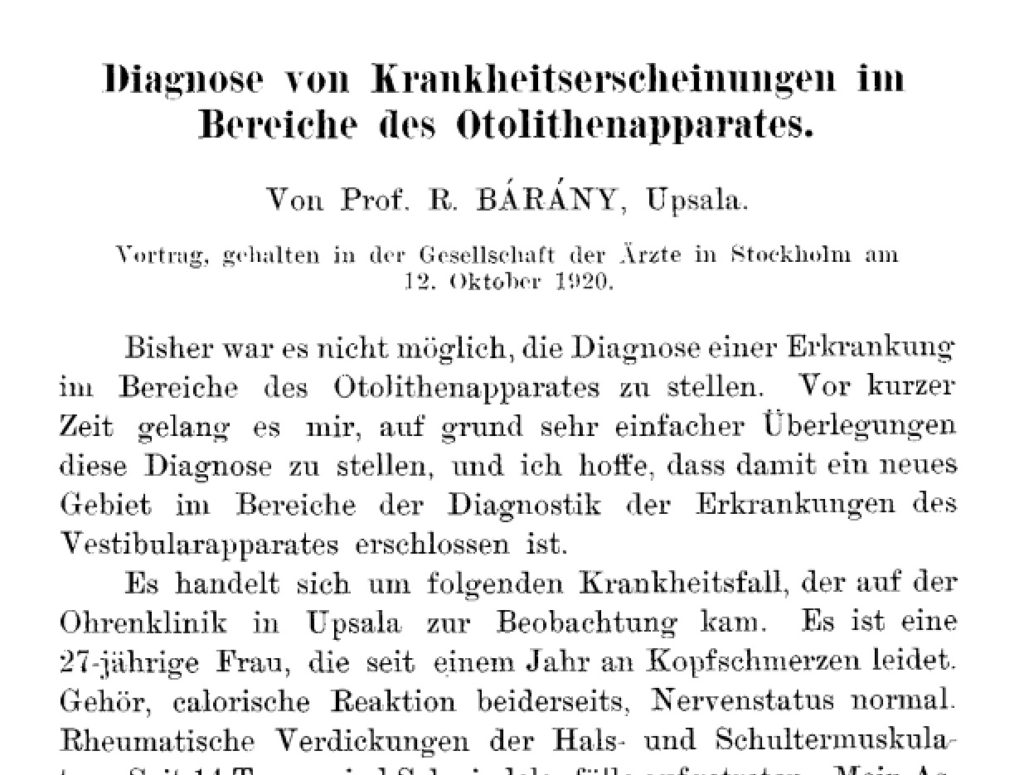

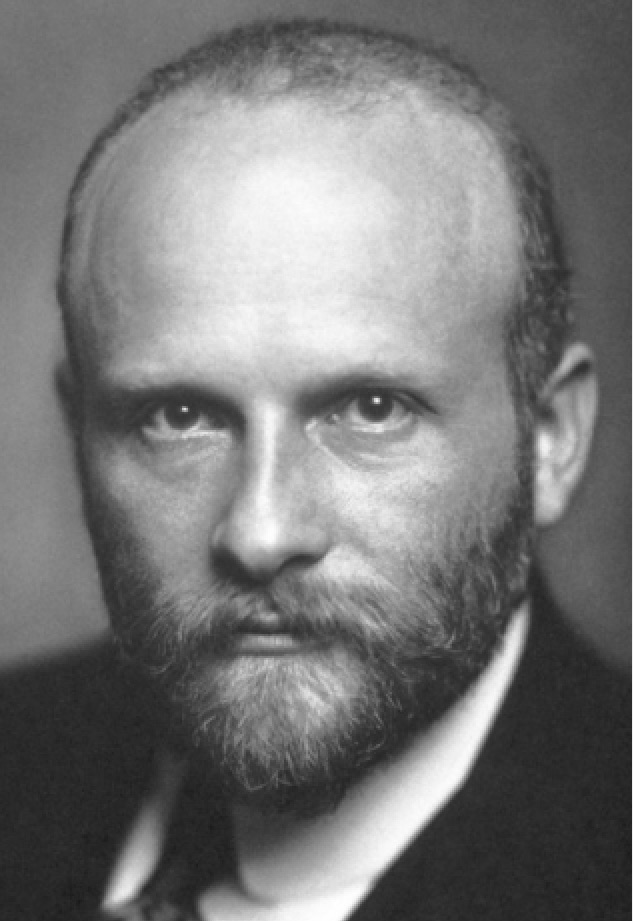

The first modern description of vertigo, however, was almost four hundred years after Romeo and Juliet when, in  1897, a Dr. D. Adler (it has, thus far, not been possible to identify this Adler’s first name) of Breslau wrote Ubeden einseitengen Drehschwindel(very loosely translated as ‘about one-sided vertigo’). A quarter century later the article by Robert Bárány, of Upsala, Diagnose von krankheitserch-eingungen im mereich dedisorders of the vestibular apparatus of the ear

1897, a Dr. D. Adler (it has, thus far, not been possible to identify this Adler’s first name) of Breslau wrote Ubeden einseitengen Drehschwindel(very loosely translated as ‘about one-sided vertigo’). A quarter century later the article by Robert Bárány, of Upsala, Diagnose von krankheitserch-eingungen im mereich dedisorders of the vestibular apparatus of the ear  otolithenappartes (even more loosely, ‘the diagnosis of symptomatic diseases of the semi-circular canals’) contributed considerably to our understanding of vertigo and similar conditions. Bárány was awarded a Nobel Prize and has come to be

otolithenappartes (even more loosely, ‘the diagnosis of symptomatic diseases of the semi-circular canals’) contributed considerably to our understanding of vertigo and similar conditions. Bárány was awarded a Nobel Prize and has come to be regarded as the founder of the modern study of these disorders; The Barany Society is the international society devoted to research in this field.

regarded as the founder of the modern study of these disorders; The Barany Society is the international society devoted to research in this field.

My vertigo began at the beginning of May, about the time we were all becoming numb to the idea of self-quarantine because of COVID-19. Two days before, and for unrelated reasons, my physician suggested increasing the dose of one of my medications. That night, when I lay down for sleep, the ceiling started spinning – I can think of no better way to describe it. I could visualize at least three ceilings and they seemed to be in a pattern of rotation. It was a startling and fascinating experience and I rose up and lay down again a few times to both confirm it was actually occurring and that I was observing it correctly. After repeating the process a few more times to study the sensation, thinking I might want to put it in a piece of writing, I decided to get some water. When I got out of bed to walk to the kitchen, the entire room reeled, this time without a distinct image, requiring me to grab a piece of furniture to maintain my balance.

Two things need to be understood at this point of the narrative:

- One of the first things I was taught in medical school was the old adage, “A doctor who treats himself has a fool for a patient.” I have always believed this to be true while regularly, along with most physicians, ignoring it.

- Pathologists, who know more about the bad things that can happen to a human being than anyone, almost always think of the worst possible outcomes long before considering the best when they or family members have a medical complaint.

So, as I am clutching at whatever I can find to keep my balance, I ask myself if it could be a brain tumor. Too many dear friends have, over the years, died of glioblastoma and other brain tumors, and I wondered if I was next. Without going into a long discussion about my reasoning at the time, I rapidly considered the typical symptoms and signs that could indicate some space-occupying lesion in my head and decided that diagnosis unlikely. My next question—by now the vertigo had abated—was: could it be from the increase of the dose of the medication? Easy to resolve in this modern world where Google, the world’s greatest library, available at your fingertips, can provide all answers. Lo and behold, that medication is associated with vertigo!

The next day an email to the physician who prescribed the drug and increased the dose confirmed the possibility. He advised stopping the medication for a while. In a few days I was scheduled to visit a neurologist for an unrelated matter and she carried out a variety of neurologic tests—she was able to provoke the rapid, involuntary repetitive motion of my eyes to one side (nystagmus)—and concluded I had “benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.” She recommended a series of ‘Epley exercises’ which exemplify Bonvolio’s advice. Three days later my vertigo was gone, providing another ‘lo and behold’ moment: “Google medicine” does not always help!!

What happens when you do the Epley exercises? A prevailing explanation for the onset of vertigo is that a tiny stone (“lithos” in Greek, as in cholelithiasis or gallstones), known in the ear as ‘otoconia,’ is displaced from its usual position (the ‘utricle’) in the inner ear and moves into, and obstructs, one of the semicircular canals preventing the shift of hydraulics necessary to maintain balance. Otoconia are small, highly dense calcific crystals exclusively associated with inner ear structures, including the utricle and the saccule. In mice, a genetic model was developed that leads to the formation of abnormally large calcium carbonate minerals with subsequent hearing loss and severe balance defects. In humans, the Epley maneuvers help move the otoconia (ear stones) from their abnormal position back to where they should be, allowing for the free flow of fluid in the semi-circular canals and the restoration of balance.

Revisiting the Hitchcock film reminded me that Jimmy Stewart’s character, the former police detective John (“Scotty”) Ferguson, has two potentially disabling disorders: he suffers from acrophobia (a severe fear of heights) as well as vertigo. Indeed, confronting heights provokes the vertigo. The rest of the story, with its typical Hitchcockian surprise, will not be divulged here – see the film. Twenty years after Vertigo was released, Mel Brooks, the comic genius who created The Producers, one of the funniest films ever made, parodied Vertigo in his satirical production,  High Anxiety. Brooks’ protagonist’s name, Richard Thorndyke, is clearly, and most likely deliberately, reminiscent of the main character in Hitchock’s other great film, North by Northwest, Roger Thornhill.

High Anxiety. Brooks’ protagonist’s name, Richard Thorndyke, is clearly, and most likely deliberately, reminiscent of the main character in Hitchock’s other great film, North by Northwest, Roger Thornhill.

What precipitated my vertigo? I also have, for about ten years, a mild form of hyperparathyroidism (increased activity of the parathyroid glands, one of the functions of which is to regulate calcium metabolism). Could I have had a sudden burst of parathyroid activity with subsequent increase of calcium levels (‘hypercalcemia’) depositing on, and causing enlargement of, those tiny grains of sand. That is unlikely since a recent blood calcium determination was unchanged. More importantly, four months later, I remain happily free of vertigo, still taking the same medicines I was taking before it developed and without the development of any other troublesome signs or symptoms.

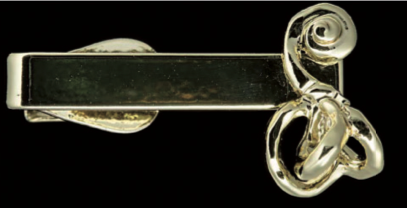

Moses Wharton Young, M.D., Ph.D. taught neuroanatomy to my medical school class.  He was a pioneering investigator of the anatomy of the ear. He simplified a known technique and gently forced metals with low melting point into the inner ear portion of the temporal bone of cadavers from which all soft tissues had been chemically removed. With this method he was able to demonstrate the inner ear labyrinth, discovering the endolymphatic duct (ductus endolymphaticus; Wharton duct), which can also be seen in the diagram above. He typically wore a tie-pin of the semicircular canals created with the

He was a pioneering investigator of the anatomy of the ear. He simplified a known technique and gently forced metals with low melting point into the inner ear portion of the temporal bone of cadavers from which all soft tissues had been chemically removed. With this method he was able to demonstrate the inner ear labyrinth, discovering the endolymphatic duct (ductus endolymphaticus; Wharton duct), which can also be seen in the diagram above. He typically wore a tie-pin of the semicircular canals created with the same technique. Sadly, Young’s story is a vivid example of institutional racism. As one of many examples, his work was ignored, despite being published in highly reputable journals and, for a time, others received He was a brilliant and highly entertaining teacher and I vividly remember that the first neuroanatomy lecture when he introduced the subject by saying that learning neuroanatomy was as easy as A, B, C. It took me very little time to realize that, at least for me, that was not true.

same technique. Sadly, Young’s story is a vivid example of institutional racism. As one of many examples, his work was ignored, despite being published in highly reputable journals and, for a time, others received He was a brilliant and highly entertaining teacher and I vividly remember that the first neuroanatomy lecture when he introduced the subject by saying that learning neuroanatomy was as easy as A, B, C. It took me very little time to realize that, at least for me, that was not true.

Although my vertigo is happily just a memory I now share a newly common disorder with almost everyone: ‘cabin fever.’ I mostly keep busy with writing, reading, movies I would never have seen otherwise, two-and-a-half-mile walks and active correspondence (emails, occasional forays into Facebook and even some old-fashioned hand-written notes). It is likely that we will remain mostly isolated until early 2021. In order to combat the ennui, Kate and I  recently started a 1000-piece jigsaw puzzle of van Gogh’s Starry Night, clear evidence of the need for diversion as well as of a not completely latent tendency for masochism.

recently started a 1000-piece jigsaw puzzle of van Gogh’s Starry Night, clear evidence of the need for diversion as well as of a not completely latent tendency for masochism.

August 9, 2020 at 6:37 pm

Stephen, at first it sounded like a bad LSD Trip. But I highly doubt that you have ever taken the drug. When I was operated on at HSS for my scoliosis they released me only to suffer the same whirling of my surroundings. It was the drugs and as you know when you visited me I fractured my vertebrae requiring a second surgery due to a severe fall. This vertigo sounds as though you were telling my story. I am glad you did suffer the same fate as I. You, being highly educated and astute in medicine have done your history and research. Expect nothing less from you. Nice background and history

August 10, 2020 at 12:24 pm

Elliot,

I’m not sure if my not ever taking LSD is a compliment or an insult. Either I have been wise and mature or timorous and sheltered (more of the latter than the former, I suppose). In any event thank you for the kind comments. Best wishes and stay safe!

August 9, 2020 at 8:29 pm

I too suffered a heavy case of BPPV (benign post-traumatic positional vertigo) for a few days, swiftly corrected with an Epley maneuver. On the occasions of blessed,y very rare minor recurrences, I can never remember on which side to perform the maneuver, but it goes away whatever I do.

August 13, 2020 at 11:51 pm

I think the Epley diagram in the post may help.

August 10, 2020 at 7:04 am

Dr Geller

only those who, at least once, experienced vertigo, will understand your distress. I also had it once, fortunately without recurrence. Thank you for sharing your brilliant testimony and historical research

August 10, 2020 at 3:41 pm

Benign positional vertigo is induced in me with decline bench press, super heavy squatting and drinking tequilla or mescal! Two of these things I have had to give up — I will let you guess which!

August 13, 2020 at 11:54 pm

I was about to start bench pressing and heavy squatting. Thanks for the warning.

August 10, 2020 at 4:32 pm

thank you for sharing this vertigo history and your experience. Drink plenty of water and less alcohol. Pray for the vaccine to come soon and good luck with “Starry Night” and keep your ear.

August 10, 2020 at 4:42 pm

Hi Dr. Geller, thank you again for the educational, well written essays. Interesting history about vertigo. I tried googling Adler from Breslau to see if something somewhere listed his first name and could find nothing – I guess we will never know his first name (and you can’t find everything on google!). Good luck with the puzzle. I did a few 1000-1500 piece puzzles with my kids but we are stuck and probably going to be giving up on #4 (a Star Wars puzzle) as we’ve only managed 25 pieces in the last several weeks. Amir

August 13, 2020 at 11:39 pm

I love how you managed to combine medicine, history, literature, hollywood, your personal experience and a touch of illustrations in just the right doses fo produce a very entertaining narrative.

Fascinating tie pin by the way…

Can’t wait for your next blog

August 15, 2020 at 6:55 pm

I thoroughly enjoyed your essay on vertigo, complete with the historical, cultural, and literary references that accompany the description of your experience with the condition. But, unlike some of the other friends of yours who commented on this page, I cannot add a personal story of experience with vertigo. I have never suffered from the condition.

However, I was intrigued by your reference to Moses Wharton Young, M.D., Ph.D., your neuroanatomy professor who discovered the endolymphatic duct. That’s where your essay becomes personal for me. At my first follow-up visit after my second cochlear implant surgery (performed in my “bad” ear) in December 2011 at UCSD School of Medicine, my surgeon walked into the exam room and announced that he knew the cause of my deafness. He said that I have enlarged vestibular aqueducts (EVA). He told me that he saw a large bulging endolymphatic sac during surgery and called residents over to the operating microscope to see it. (Apparently, scientists do not think that EVA causes hearing loss. Instead, they think that both conditions are caused by the same underlying defect, whatever it is.) A neuroradiologist later reviewed my MRI scans with my surgeon and confirmed the diagnosis.

I do not know if my first surgeon at UCSF was aware of the diagnosis, because he never told me. My UCSF surgeon had operated on my “good” side, the side where he said I had a greater likelihood of success with an implant. Perhaps the bulging sac was not as prominent due to a defect that might have been smaller.

I was told throughout my childhood that I am congenitally deaf. However, deafness associated with EVA is not congenital. But how would my childhood ENT specialist have known? Most of the 372 articles in PubMed on EVA have been published since the late 1990s. The first one was published in 1984. It would not have been possible to either recognize or make the diagnosis of EVA before CAT scans and MRI scans started to be used widely in medicine. (I had an MRI scan as part of pre-op for my first cochlear implant surgery in 2006.)

So, after all these years, it turns out that I am pre-lingually deaf, not congenitally deaf. My speech therapist at the Queens College Speech and Hearing Center studied tapes of my speech for years, reviewing them with students and other speech therapists in an effort to figure out how I had learned to speak as well as I do. He had hoped to figure out how he had been so successful with me and then apply the lessons to his work with other congenitally deaf children.

It is well known that children who become deaf after birth but before they become lingual have a much easier time acquiring verbal language than do children who are congenitally deaf. I now know that I had had an advantage in learning speech over congenitally deaf children. I wondered if I should contact my speech therapist to let him know. He was fresh out of training and probably in his mid-20s when he became my speech therapist. I figured that he might still be alive but would, in all likelihood, have long since retired by 2011. I had last been in touch with him almost 30 years earlier in 1982. Why disappoint an old man in retirement when he had been so proud for so many years of teaching me to speak? But the decision was made for me when I googled his name and learned, unfortunately, that he had died 10 years earlier, still a professor at Queens College.

Oh, wait. I suffered some mild dizziness the evening after my first cochlear implant surgery. Does that qualify as “vertigo”? But from your description my case was far milder. I simply lay down on the couch and enjoyed having my husband and children cook dinner and clean up without me. By the next day, the dizziness was gone.

October 25, 2020 at 6:52 pm

Steven:

I have had vertigo with similar symptoms to yours a few months ago. I experienced the spinning ceiling upon awaking. The ceiling in my bedroom exacerbated the effect because heavy beams support the ceiling. It was like looking at interlocking propellers.

I’m sure the cause too much wine the previous night. In any case it went away after lying in bed for about fifteen minutes. I hasn’t reoccurred so I am ignoring it.

There are some vivid descriptions of vertigo in Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot.