In these troubled times, as America continues to struggle with, and hopefully comes closer to resolving, the issue of racism decried throughout our history and by so many of our nation’s greatest leaders, I am reminded of Thomas Hodgkin, whose birthday is August 17, the date of this posting. Hodgkin, an early 19th century London physician is remembered for the condition once called “Hodgkin’s disease” and now known as “Hodgkin lymphoma.”

There was a time when eponyms in medicine were omnipresent. There are books about eponyms and many of us, who ‘grew up’ in former times, love eponyms because of the stories that accompany the honor. Eponyms are no longer in style and those that remain reflect the fact that a better, simpler, more scientific label has not been recognized or because the nature of the disorder is still not completely understood, or both. This is true for Hodgkin lymphoma. There will likely come a time, in the not-too-distant future, when a cogent argument for a new name is proposed and accepted and the name Hodgkin disappears into the mist of history. That will be a great shame since Thomas Hodgkin was far more than a brilliant physician and “morbid anatomist” (the name formerly used for those who perform autopsies).

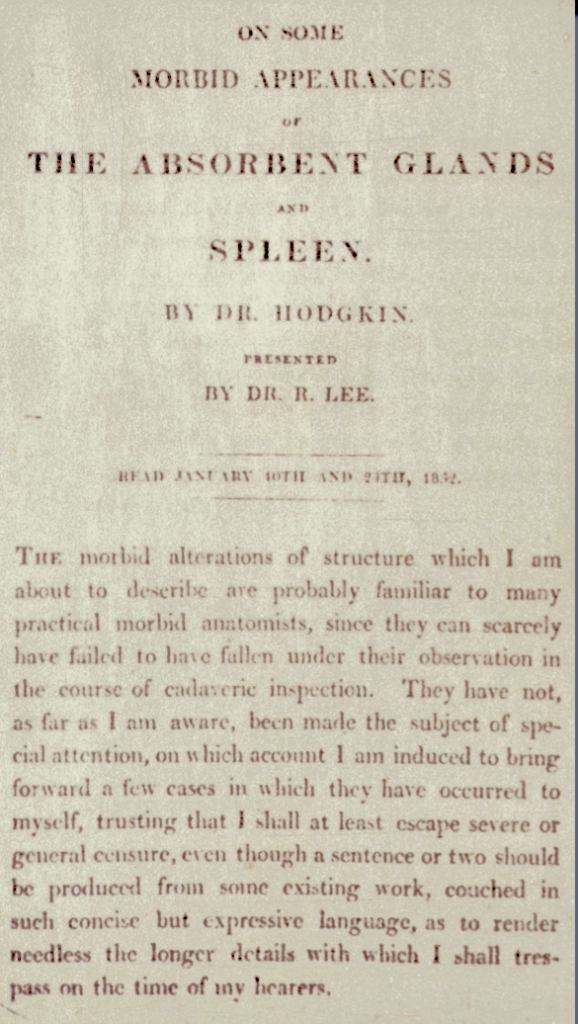

Thomas Hodgkin (August 17, 1798-April 5, 1866) introduced his discussion of the condition we now know as Hodgkin Lymphoma with modesty characteristic of his entire life, indicating, in his first sentence, that his findings were “probably familiar to many practical morbid anatomists.” Although there is evidence that he was, to a degree correct in that Marcello Malpighi (1628-1694), one of the greatest scientists of all time, described a finding that most likely is the same as the one Hodgkin recognized. When Hodgkin learned of the Malpighi paper he added a footnote acknowledging it. A few others also wrote about the condition although the significance of the change was not mentioned. Hodgkin’s 1832 publication, however, was indisputably original and did more than describe a change in morphology; it altered the way disease processes, including malignant tumors, are considered.

Hodgkin’s paper reflected his long interest in what were called ‘the absorbent glands’ (lymph nodes) and the spleen, the subject of his thesis for graduation from the University of Edinburgh medical school (his doctoral thesis was commended only for the quality of the Latin – Hodgkin’s father, John, was a teacher of Greek and Latin).

It is worth noting, as the published copy of the presentation given before the Royal Society indicates, that Hodgkin  did not, himself, give the lecture. Instead, it was presented by his friend, Dr. R. Lee. Hodgkin, as a member of the Society of Friends, a Quaker, and not of the Church of England, was not permitted to present it himself. Thomas Hodgkin was all too familiar with bigotry and discrimination. In fact, that is the reason he went to medical school in the more progressive and less discriminatory University of Edinburgh rather than attending a school in England. When he was still a medical student he went to Paris to hear the lectures of Rene Theophile Hyacinth Laennec (1781-1826), who was the foremost physician in Europe. Laennec later wrote that Hodgkin was one of the finest students he had ever known. Hodgkin introduced Laennec’s invention, the stethoscope, to British medical practice.

did not, himself, give the lecture. Instead, it was presented by his friend, Dr. R. Lee. Hodgkin, as a member of the Society of Friends, a Quaker, and not of the Church of England, was not permitted to present it himself. Thomas Hodgkin was all too familiar with bigotry and discrimination. In fact, that is the reason he went to medical school in the more progressive and less discriminatory University of Edinburgh rather than attending a school in England. When he was still a medical student he went to Paris to hear the lectures of Rene Theophile Hyacinth Laennec (1781-1826), who was the foremost physician in Europe. Laennec later wrote that Hodgkin was one of the finest students he had ever known. Hodgkin introduced Laennec’s invention, the stethoscope, to British medical practice.

Lymph nodes often enlarge with infections or with other inflammatory disorders. Hodgkin recognized the distinct nature of the condition he observed and indicated clearly that he was studying a condition unrelated to the usual forms of lymph node disease which were inflammatory: “ … this enlargement of the glands appeared to be a primitive (today, we would say neoplastic or even malignant) affection of those bodies, rather than the result of an irritation propagated to them from some ulcerated surface or other inflamed structure.”

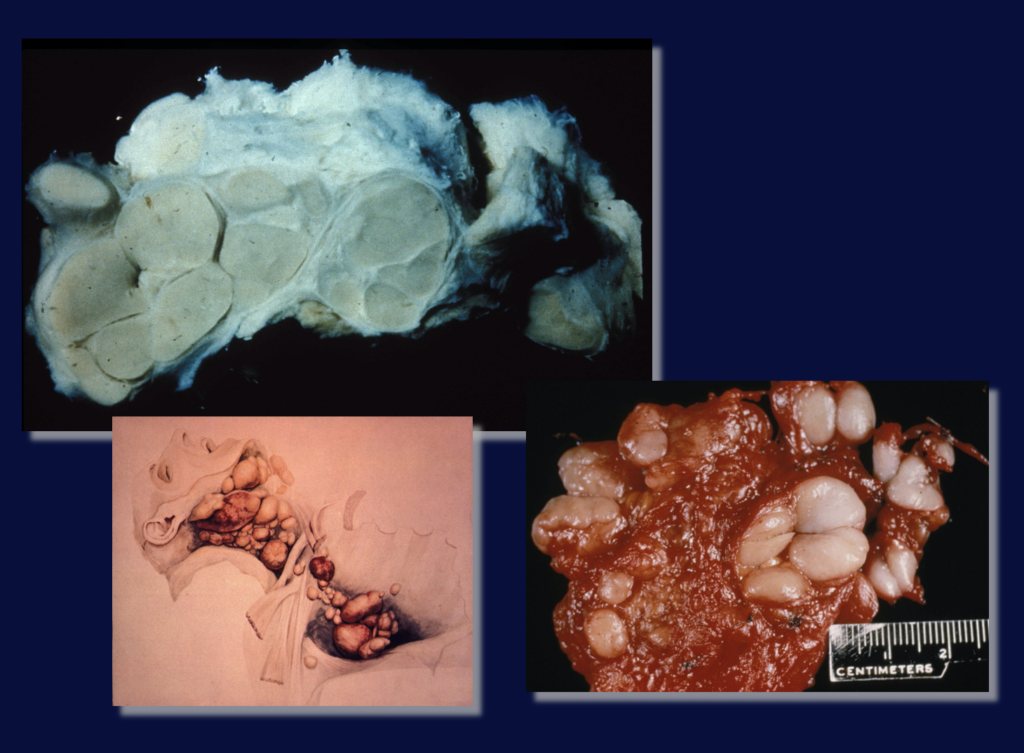

Hodgkin was a pioneering microscopist, working with Joseph Jackson Lister (1786-1869), a physicist and microscopist (and father of Joseph Lister (1827-1912), the developer of antiseptic surgery). At the time, however, microscopy was not used in medical practice and Hodgkin only studied his cases macroscopically (i.e. grossly, without the aid of magnification). This composite image shows, at the top left, one of the actual specimens Hodgkin prepared from an autopsy of someone  with Hodgkin lymphoma and, below that, is the illustration that was used at the time of the presentation. In addition, you can see, to the right a surgically resected specimen from a patient in the early 1960’s when surgery was erroneously thought to be useful in treating the disorder. Without going into a detailed discussion of the things that differentiate Hodgkin lymphoma from other conditions you can see that each greatly enlarged lymph node maintains its individual shape, in contrast to non-Hodgkin type lymphomas which tend to fuse together. Uninvolved, “normal” lymph nodes are generally very small and may not be grossly visible.

with Hodgkin lymphoma and, below that, is the illustration that was used at the time of the presentation. In addition, you can see, to the right a surgically resected specimen from a patient in the early 1960’s when surgery was erroneously thought to be useful in treating the disorder. Without going into a detailed discussion of the things that differentiate Hodgkin lymphoma from other conditions you can see that each greatly enlarged lymph node maintains its individual shape, in contrast to non-Hodgkin type lymphomas which tend to fuse together. Uninvolved, “normal” lymph nodes are generally very small and may not be grossly visible.

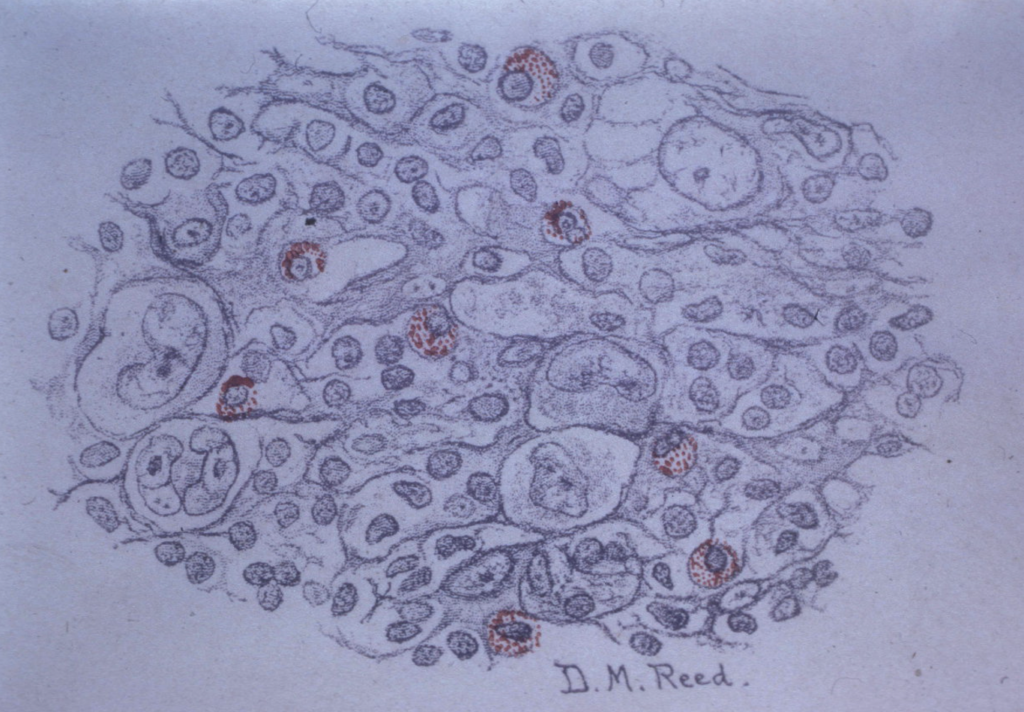

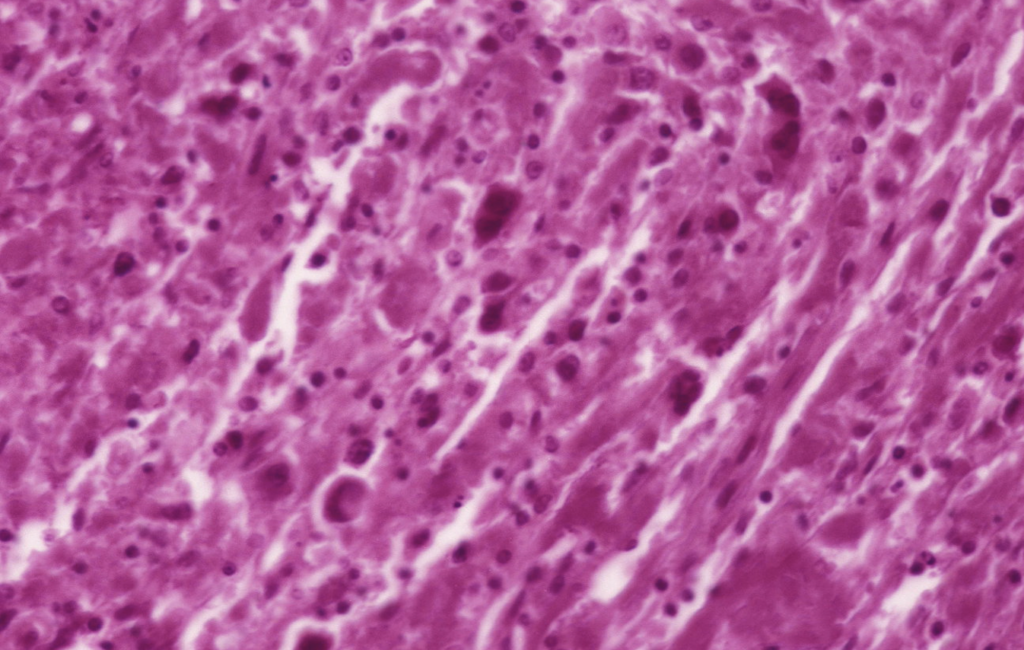

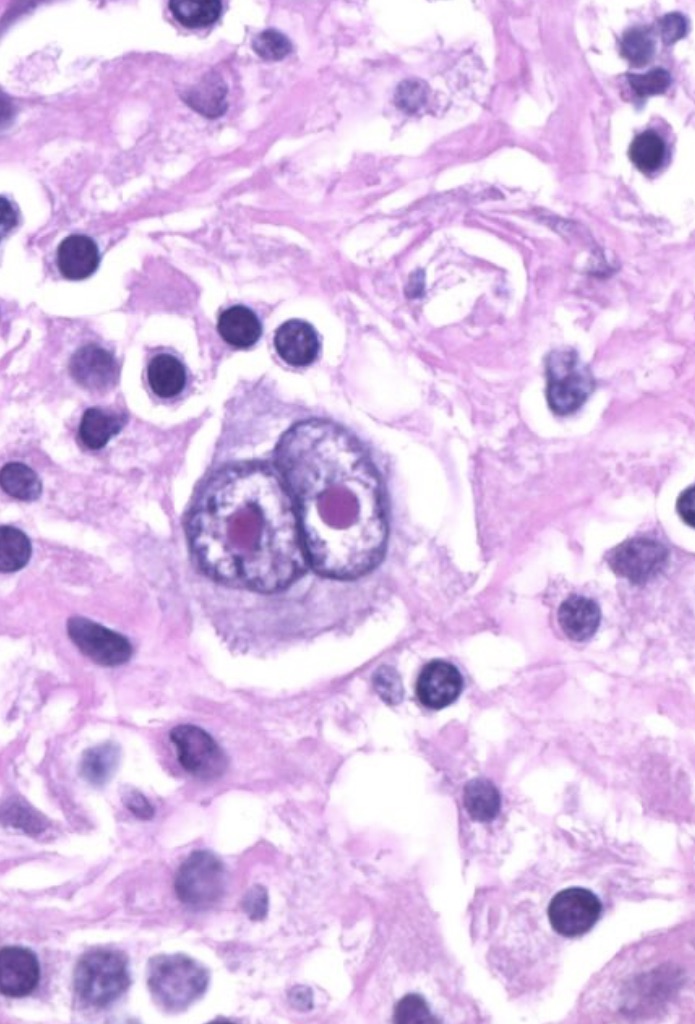

The characteristic microscopic features of the disease were recognized in the first years of the 20thcentury, at almost the same time by the Austrian pathologist, Professor Carl Sternberg (1872-1935) and the young American, Dorothy Reed (1874-1964), who began her studies when she was still a student at Johns Hopkins medical school and continuing them after graduation when she was a pathology  fellow. Sternberg did not realize he was studying the disease Hodgkin described but Reed did and illustrated the characteristic giant cell of this unique condition. The Reed-Sternberg cell is a greatly enlarged cell, often with two kidney-bean shaped nuclei facing each other showing a prominent intranuclear body (nucleolus) which, in contrast to the typical blue color of nuclei, has a purplish or red tint, shown to the left in Reed’s drawing. To the right of the Reed drawing is a photomicrograph of a modern case highlighting the large binucleate Reed-Sternberg cell. In 1926, almost a century after the seminal paper, a Philadelphia pathologist, Herbert Fox, recovered the original cases that were still stored at Guy’s Hospital (in the modern world of medicine specimens are discarded after a few years, except at very few institutions). Fox prepared microscopic slides to confirm the diagnosis in some of the original cases. The image to the far right is from one of the slides prepared by Fox. The quality of the almost 100-year-old tissue, preserved under less than ideal conditions, does not match either Reed’s drawing or material prepared in almost any lab today, but you can still see the very large Reed-Sternberg cells. In recent years these Hodgkin cases have been subject to the most sophisticated immunohistochemical studies which have shown them to be unequivocally what we now call Hodgkin Lymphoma. Hodgkin, of course, never applied his own name to the cases but, a half century later, Sir Samuel Wilks (1824-1911), a leading physician at Guy’s wrote about similar cases and, having identified Hodgkin’s original paper, proposed appending his name.

fellow. Sternberg did not realize he was studying the disease Hodgkin described but Reed did and illustrated the characteristic giant cell of this unique condition. The Reed-Sternberg cell is a greatly enlarged cell, often with two kidney-bean shaped nuclei facing each other showing a prominent intranuclear body (nucleolus) which, in contrast to the typical blue color of nuclei, has a purplish or red tint, shown to the left in Reed’s drawing. To the right of the Reed drawing is a photomicrograph of a modern case highlighting the large binucleate Reed-Sternberg cell. In 1926, almost a century after the seminal paper, a Philadelphia pathologist, Herbert Fox, recovered the original cases that were still stored at Guy’s Hospital (in the modern world of medicine specimens are discarded after a few years, except at very few institutions). Fox prepared microscopic slides to confirm the diagnosis in some of the original cases. The image to the far right is from one of the slides prepared by Fox. The quality of the almost 100-year-old tissue, preserved under less than ideal conditions, does not match either Reed’s drawing or material prepared in almost any lab today, but you can still see the very large Reed-Sternberg cells. In recent years these Hodgkin cases have been subject to the most sophisticated immunohistochemical studies which have shown them to be unequivocally what we now call Hodgkin Lymphoma. Hodgkin, of course, never applied his own name to the cases but, a half century later, Sir Samuel Wilks (1824-1911), a leading physician at Guy’s wrote about similar cases and, having identified Hodgkin’s original paper, proposed appending his name.

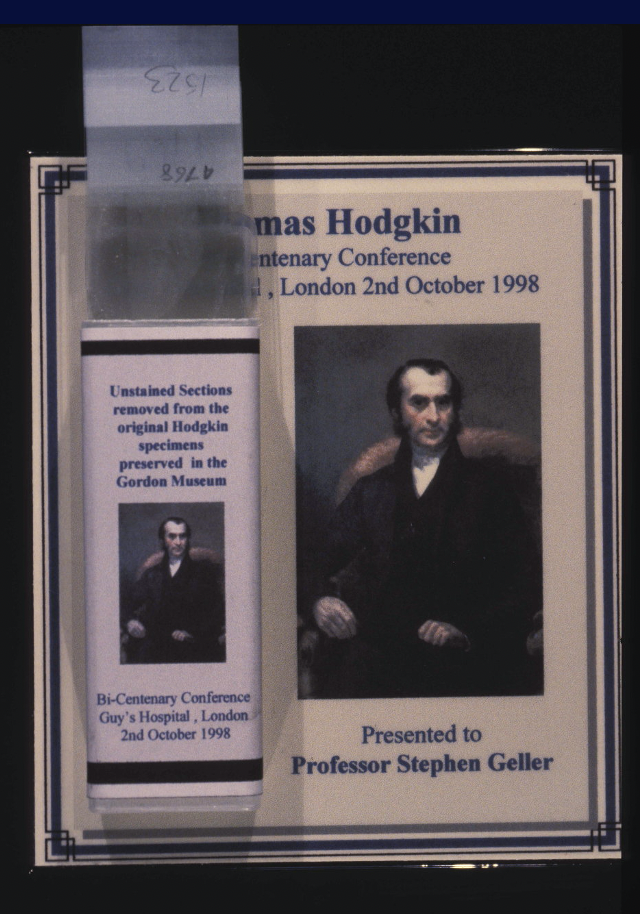

In 1996 I wrote to a physician I knew at Guy’s hospital asking if there would be a celebration, in 1998, of Hodgkin’s 200th birthday, and could I attend? To my great surprise, no one at Guy’s had yet thought about it. Eventually a scientific symposium was held to honor Hodgkin on October 2, 1998. Happily, I was invited and, to my great delight, I was presented with a small container in which there are slides prepared from the material Hodgkin first studied. I will eventually pass this treasure of history on to some young hematopathologist.

Thomas Hodgkin might well be considered the first pathologist since he devoted himself almost entirely to performing autopsies and, apparently with some reluctance, took care of very few patients except for Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore, for whom he served as physician. Hodgkin was, however, far more than a pathologist who made a historic discovery. Hodgkin was the first to describe and/or understand a number of other conditions (he wrote about cholera, diabetes, atherosclerosis, aortic valve regurgitation and much more). He made major contributions to the understanding of disease and was a highly regarded diagnostician. His honesty was beyond question. As an example, he performed an autopsy on a patient who died after surgery for removal of a bladder stone failed. The actual stone, cut in half, is still in the museum at Guy’s Hospital. When Hodgkin went into the next room for a minute or two, a reporter for the then new Lancet magazine, reached into the body and claimed the surgeon had made a hole into the rectum. In that time Lancet was more of a muckraking tabloid than a distinguished medical journal. When Hodgkin returned, he said, in the manner he usually spoke, “If there is a hole, sir, then thou hast made it.” No one—not even the Lancet—doubted Hodgkin and, in a subsequent libel suit brought by the surgeon, the Lancet lost.

Far ahead of the times in many ways, he recommended that medical students learn chemistry, physics and other basic sciences a century before that became the practice. He wrote about creating a hospital position for new physicians to learn how to practice, what we now call a “residency.” He was a particularly efficient administrator, developing the now-famous ‘green books’ for keeping records of all autopsy findings. He created one of the first medical museums, now known as the Gordon Museum at Guy’s Hospital. Rather than just storing preserved specimens he displayed them in systemic order (i.e. lungs with lungs, hearts with hearts, etc) reasoning that such an arrangement would make learning easier and more efficient. He was a renowned teacher and a pioneering proponent of the autopsy as an integral component of medical practice.

Despite all his accomplishments, and the high regard in which he was held by the medical community, he was not appointed to replace Richard Bright (1789-1858) who was stepping down as senior physician at Guy’s. In the same year he was further disappointed when the Society of Friends forbid him to marry Sarah Godlee, his close friend since childhood but also his first cousin. He would later study marriages of closely related people, as well as animals, and publish a once widely quoted paper on the topic.

Hodgkin’s professional achievements pale when compared to his humanitarian pursuits. Hodgkin was a good and decent man, a humanist in every sense of the word. He was a man of great morality whose honesty was beyond reproach. Among his many interests were anthropology, geology, geography and ethnography. He helped found the University of London. He denounced poor sanitation in London, overcrowding, lack of adequate fresh air, employment of children as chimney sweeps and the inhalation of dust particles by factory workers, recommending protection of breathing by “a mass of light cotton wool, tied before the face” (it is hard to imagine what he would have thought of those people, who are either exceedingly selfish or stupid, now protesting against face masks). He noted that “smoking tends to encroach on the freedom and comfort of others.” He was outspoken in his opposition to slavery.

Following his two disappointments he devoted a great proportion of his time to philanthropic activities. He denounced conditions of poor sanitation in London, overcrowding, lack of adequate fresh air in the city, and the employment of children as chimney sweeps and factory workers. He vigorously promoted vaccination for smallpox. He wrote a paper about remuneration for medical care in which he urged his fellow physicians to be mindful of their responsibilities to care for the poor. In that same paper he proposed the concept of prepaid medical insurance. He spoke about the dangers of second-hand smoke. He proposed the creation of face masks for use by workers in dusty environments. When Joseph Lister was a young man, Hodgkin treated him for what we would now call a “nervous breakdown.” At one time, Hodgkin served as the key witness in the trial of Edmund Oxford, who had tried to kill Queen Victoria in 1840. Oxford was acquitted on the basis of insanity, three years before the same argument was used in the trial of Daniel McNaughton, whose name is applied to that legal defense.

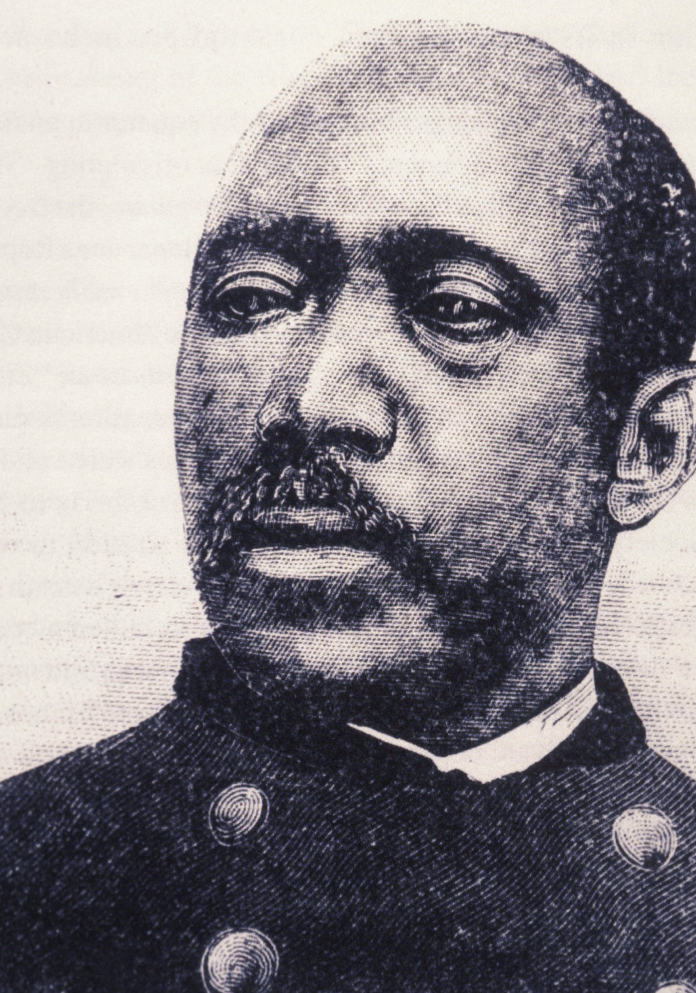

Hodgkin was a linguist (Latin, Greek, French, Italian, Spanish, German), ethnologist, anthropologist, geologist. He was a leader of the Royal Geographical Society and one of the founders of the University of London. He was particularly devoted and vociferous opponent of slavery and had a passionate interest in the fate of indigenous peoples, particularly native North Americans and African Americans. He was a founder of the Aborigines Protection Society which was mostly devoted to the abolition of slavery. One of the reasons he may not have been appointed as Bright’s successor was that he drove his carriage with a native American Indian chief, in full regalia including an elaborate feather head-dress, around the courtyard of Guy’s Hospital, which infuriated Benjamin Harrison, Treasurer (chief executive) at Guy’s Hospital who had final say on all hospital appointments. Harrison was one of the owners of the Hudson Bay Trading Company and, at least indirectly, party to practices Hodgkin abhorred. Hodgkin also befriended Martin Delaney Robison (1812-1885), an African-American abolitionist, journalist, physician (he was one of the first Black men admitted to Harvard Medical School), soldier (the only Black officer to receive the rank of Major in the civil war) and writer, as well as friend and colleague of Frederick Douglass.

Martin Delaney Robison (1812-1885), an African-American abolitionist, journalist, physician (he was one of the first Black men admitted to Harvard Medical School), soldier (the only Black officer to receive the rank of Major in the civil war) and writer, as well as friend and colleague of Frederick Douglass.

Hodgkin’s last years were completely devoted to self-sacrificing activities to better the conditions of the poor, to abolish slavery and to relieve the persecution of the Jews in Africa and the middle east.

His close and devoted friend, Sir Moses Montefiore, a financier and banker for the Rothschild family, was extremely wealthy. They first met when Hodgkin was in medical school and they travelled widely together, striving to improve the status of the many who lived desperate lives. (After one trip, Hodgkin wrote “A Journey to Morocco,” which he illustrated with his own beautiful water-color paintings). In 1866 Hodgkin and Montefiore went to the Holy Land to aid distressed Jews and Arabs who were in the midst of a cholera epidemic.

His close and devoted friend, Sir Moses Montefiore, a financier and banker for the Rothschild family, was extremely wealthy. They first met when Hodgkin was in medical school and they travelled widely together, striving to improve the status of the many who lived desperate lives. (After one trip, Hodgkin wrote “A Journey to Morocco,” which he illustrated with his own beautiful water-color paintings). In 1866 Hodgkin and Montefiore went to the Holy Land to aid distressed Jews and Arabs who were in the midst of a cholera epidemic.

Hodgkin became acutely ill with severe abdominal pain soon after they arrived in Alexandria. It may have been cholera or some other dysenteric disorder or, since Hodgkin had abdominal pain many times during his life, diverticulitis (inflammation of tiny outpouchings in the large intestine which develop particularly in those with low fiber diets). Because it was the holy days, Montefiore, a rigidly observant orthodox Jew, was already in Jerusalem when Hodgkin died. It is one of ironies of life that this great pathologist, and great proponent of the autopsy, was, himself, not studied after death.

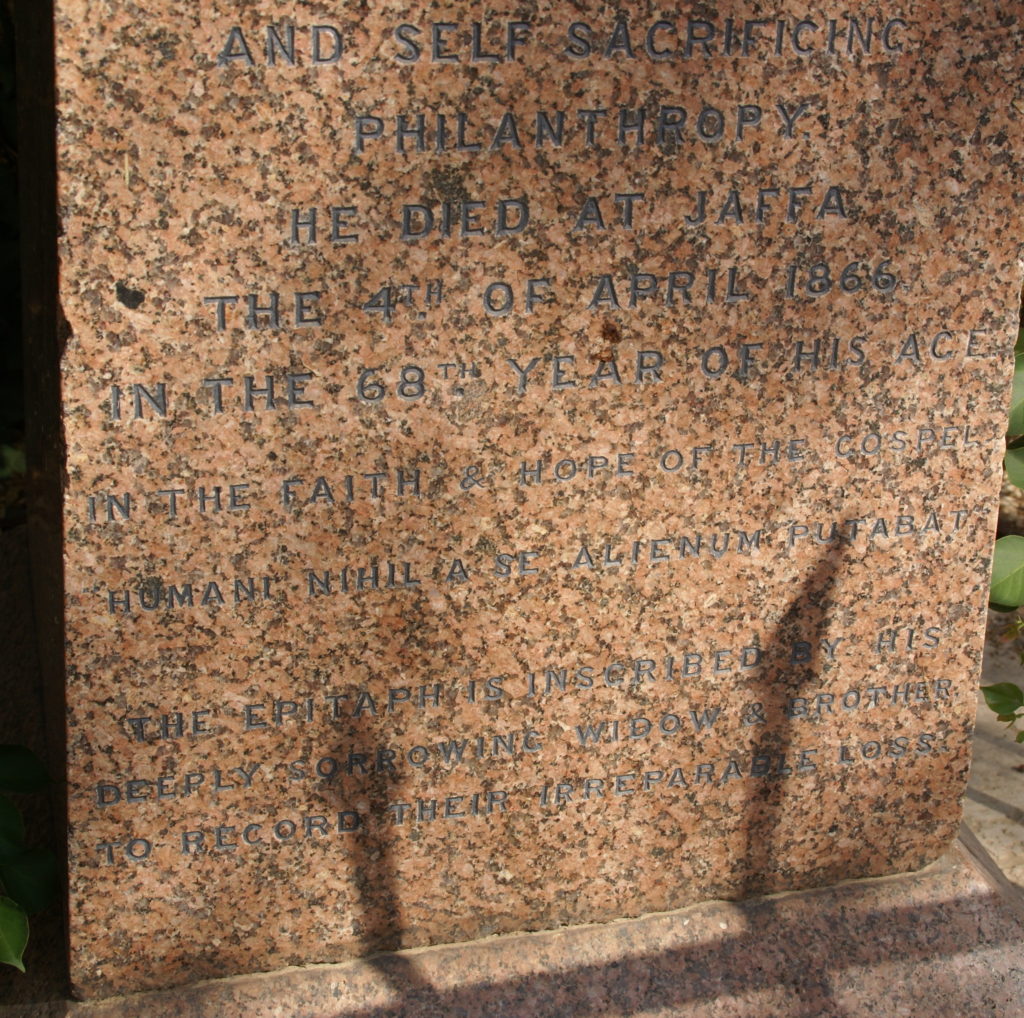

Montefiore had Hodgkin’s body transported for burial in the Anglican cemetery in Jaffa, near Tel Aviv, in what is now Israel, and had an obelisk erected to mark the grave that appropriately proclaims: Humani nihil a se alienum putabit (nothing human was foreign to him). You can make out the words carved in the marble in the fifth line.

Over the years the cemetery became overgrown and was, in effect, lost until an expedition from New York, led by the  great cardiologist Emanuel Libman (1872-1946) rediscovered it. Libman is reading a document in the photograph to the left. It became ‘lost’ again and was in in poor condition

great cardiologist Emanuel Libman (1872-1946) rediscovered it. Libman is reading a document in the photograph to the left. It became ‘lost’ again and was in in poor condition when I first visited it in the early 1980s (middle photograph). In recent years, as I can attest after visiting it again in 2016 (photograph below), the cemetery is again well maintained.

when I first visited it in the early 1980s (middle photograph). In recent years, as I can attest after visiting it again in 2016 (photograph below), the cemetery is again well maintained.

Even the casual reader has, by now, determined that I have a special interest in this remarkable man. In the early 1970’s, I was particularly interested in lymph node and spleen disorders and first read about Hodgkin himself. In 1980 I had the opportunity to spend a week in London and devoted most of my time to discovering as much as I could about him. I visited the great Reading Room of the British Museum (which no longer exists as a library), the Society of Friends House, the Wellcome Institute, the Royal Society of Medicine, the Greater London Record Office, the County Hall Archives Office and other places, including each of the addresses where he had lived from the time of birth to the time of death. In 1849, he married the widow Frances Scaife, a neighbor when he lived on Lower Brook Street. By all accounts, they lived very happily together, eventually moving into a lovely home at 35 Bedford Square, Bloomsbury.

When I first walked by that building I noticed a blue plaque denoting that Thomas Wakley, the founder and editor of the Lancet, had lived there but there was no no plaque for Hodgkin. Blue plaques, as many have seen, are throughout London commemorating places or residence or of work of the greatest English people, including writers, artists, politicians and many others, including physicians. Needless to say, this observation was troubling and, when I returned home, I began petitioning the Greater London Council to correct what I considered a grievous wrong. I soon learned I was part of a small and determined group of individuals throughout the world also writing to request the creation of a Hodgkin blue plaque. Five years, and countless letters, later I was invited to the unveiling of the second plaque to be placed on that building

There is much more to the story of Thomas Hodgkin than I have been able to squeeze into his birthday blog. You may want to read one of the biographies written about him: Kass AM and Kass EH: Perfecting the World – The Life and Times of Dr. Thomas Hodgkin (1988, considered the definitive biography), Rosenfeld L: Thomas Hodgkin – Morbid Anatomist, Social Activist (1993), Rose M: Curator of the Dead – Thomas Hodgkin – Doctor and Campaigner for Human Rights (1981). Amelie Kass, a historian, and Edward Kass had complete use of the Hodgkin papers that are maintained at the Countway Medical Library of Harvard University.

So, on this occasion of Hodgkin’s 222nd birthday, join me in lifting a cup of tea (Hodgkin probably did not drink wine) in memory of this extraordinary and distinctly humane human being.

August 17, 2020 at 2:00 pm

Dr Geller

Beautiful documentation and tribute. I will certainly drink a cup of tea and lift it in memory of T Hodgkin. Thnak you for giving us the oportunity to know a piece of his history.

August 17, 2020 at 3:04 pm

Thank you, Stephen, for this enriching article.

It is a great opportunity to thank you for the search of Thomas Hodgkin’s grave. Once finally finding out that the little cemetery had been surrounded by buildings – it turned out to be an important historical discovery. No other visitor to Israel would ask to visit the place. I was enriched. A day that we had learnt nothing is a lost day.

August 17, 2020 at 3:22 pm

Dr. Geller, Amazing essay commemorating Thomas Hodgkin! Now I have even more info I can share with residents in my dry-eraser board talks on Hodgkin lymphoma! My dad died a few days ago and his funeral was yesterday. I would occasionally forward your essays to him. He loved history. And we searched for Hodgkin’s grave many years ago in Jaffa (a few years later I found it with my mom). He definitely would have enjoyed your essay on Thomas Hodgkin. My dad was such a support to me when I was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma as a senior in high school. His love of history always inspired me and your essays are always such a joy to read and glad o got to share some of them with him. Next time I visit London I want to see the blue plaque!

August 17, 2020 at 6:57 pm

Stephen, your range of interests is incredible, as is your ability to present them in rich detail in your absorbing essays. The mark of their success is that you engender in your readers comparable appreciation of your subjects!

August 18, 2020 at 3:53 pm

Cheers! May his name continue to echo in a world that is up to his ideals.

I love how you persevere in shedding light on worthy people who are not given their right share of the limelight. As usual, your narration and photos transport us … in this case to a bougainvillea adorning Hodgkin’s grave site.

August 18, 2020 at 6:10 pm

Next time I take a trip abroad, I am going to ask you about sites of medical interest that I should visit that aren’t in the guide books.

Thank you for this very interesting essay about Thomas Hodgkin.

August 24, 2020 at 2:57 pm

Stephen, you continually amaze me with the range and depth of your thinking and the clarity of your presentation. I look forward to enjoying your sharing!

August 25, 2020 at 5:26 pm

Marvelously informative narrative from a first-class writer.