December 16, 2020

In 1970, 50 years ago, we lived in Beaufort, South Carolina. As noted in a blog post a few weeks ago (https://stephenageller.com/2020/10/12/on-listening-to-chopins-g-minor-ballade/), the city of Beaufort in North Carolina is pronounced in the French manner as ‘Bow-for,’ rhyming with the word ‘beau.’ In contrast, the South Carolina city’s name is pronounced something like ‘Bew-ferd’ or ‘bew-fert,’ the first part as in ‘beautiful.’ It’s not clear why this is so. I don’t think the North Carolina city is any more sophisticated or French than the one in South Carolina. I think the opposite may be true. I learned I would be living in Beaufort a few months before the end of my residency at The Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, when I called the Bureau of the Navy in Washington, D.C. to learn where I would be stationed for my two years of military service (in those Vietnam years more than 90% of young male physicians would be called).

No matter the pronunciation, Kate, our children, David and Jennifer, and I moved to Beaufort in late July, 1969 and lived there until the end of June, 1971.

We came to Beaufort (it helps the story to keep pronouncing it ‘Bew-ferd’) a few months after the pivotal Tet offensive of the Vietnam War, when it was increasingly apparent to many in the country (other than the nation’s civilian and military leaders) North Vietnam would eventually triumph. In the months before moving I often expressed my opposition to the war but for various reasons, not worth the time to discuss here, I accepted a commission as Lieutenant Commander in the United States Navy and was assigned to direct the laboratories at the Naval Hospital, Beaufort, S.C.. Indeed, in those years, the pathologist at the Naval Hospital was the only pathologist in Beaufort County, assisting, when needed, at Beaufort Memorial Hospital in town.

Beaufort County was the site for the second landing on the North American continent by Europeans in 1514, less than 20 years after Columbus. This Spanish Colony, led by Captain Diego Guilarte de Salazar, failed within months of its founding but Beaufort eventually became the second oldest chartered city in South Carolina, after Charleston. Beaufort is at the southern coastal tip of South Carolina, about 30-40 minutes north of Savannah, Georgia and about an hour south of Charleston.

Beaufort is at the southern coastal tip of South Carolina, about 30-40 minutes north of Savannah, Georgia and about an hour south of Charleston.

Beaufort’s native population in 1970 was approximate 9500 people, but the military population, which consisted mostly of Marines and their families, approached 50,000. The Navy was almost non-existent. There was no flotilla, no great ships, no Admirals. There wasn’t even a dock to tie up your rowboat. The Navy’s only presence in town was the hospital which, at that time, had approximately 250 inpatient beds and fewer that 300 employees, including the 25+ physicians, most of whom were, as I was, reservists serving for two years. The hospital, as you can see from the image, was designed in the shape of an  anchor, something that could not be easily appreciated from inside the building. The Marines do not have their own medical division and the hospital served two Marine bases: Parris Island, the Marine recruit training center, and the Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS). Parris Island is about 7 miles away and the MCAS about 11. The hospital long ago ceased to be an inpatient facility and now functions as an outpatient and veteran’s center.

anchor, something that could not be easily appreciated from inside the building. The Marines do not have their own medical division and the hospital served two Marine bases: Parris Island, the Marine recruit training center, and the Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS). Parris Island is about 7 miles away and the MCAS about 11. The hospital long ago ceased to be an inpatient facility and now functions as an outpatient and veteran’s center.

Before the Vietnam War, and after, Beaufort was a relatively quiet Southern town. The 1983 motion picture “The Big Chill” was filmed in Beaufort, but the few street scenes in the movie are quieter than they were in 1970 when it was a fairly bustling community with many Marine wives (almost all Marines in those days were men) and children in the community. The lovely antebellum home in which the Kevin Kline and Glenn Close characters lived in that wonderful film is typical of the residences in the better parts of Beaufort. You can also see glimpses of Beaufort in “Forrest Gump,” “The Great Santini,” and “Platoon,” and other motion pictures. Pat Conroy was from Beaufort and many of his books (e.g., “The Water is Wide,” “Prince of Tides,” “The Great Santini” and others are based there.

film is typical of the residences in the better parts of Beaufort. You can also see glimpses of Beaufort in “Forrest Gump,” “The Great Santini,” and “Platoon,” and other motion pictures. Pat Conroy was from Beaufort and many of his books (e.g., “The Water is Wide,” “Prince of Tides,” “The Great Santini” and others are based there.

At the beginning of December 1970, Kate and I were beginning to look toward the following June when I would return to civilian life but we had not yet decided where we were going. We thought we would try some place other than New York (for reasons, in hindsight, I can not understand and now can’t even imagine) but, unbeknownst to me, my chairman and mentor at Mount Sinai, Hans Popper, had already informed those who called for a recommendation because they were considering me for staff position at their institution that I was unavailable. Popper decided for me; I was going back to New York. As 1970 drew to a close, I knew nothing of this.

Beaufort was not a cultural center. We would occasionally hear a pianist or other musicians from the University of South Carolina play at the home of our friends, the Keyserlings (mentioned also in the link above) but the only other classical music we could hear was played on our Dual vinyl record turntable. I had recently obtained the turntable along with a new Sansui tuner/receiver and outstanding Sansui speakers (which I still have) and had a reasonably sized collection of vinyl recordings (there was no classical music radio station in Beaufort and this was decades before the development of the CD). I jealously read about the many concerts in New York in my copy of the Sunday New York Times (which came to Beaufort on Tuesday) and for many months was well aware that 1970 was the 200th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth. When I mentioned this to Kate, always a marvelous hostess, she said we should have a party to celebrate the occasion.

And so we did.

December 16, the likely date for Beethoven’s birth (the only written record is of his baptism, on the 17th) was on a Wednesday in 1970, so we scheduled our celebration for late afternoon on the prior Sunday. I prepared a list of the recorded pieces I would play (my choices were vast since I already had (and still have) the complete set of Beethoven’s works released by Deutsche Grammaphon records) and Kate prepared everything else.

We lived in Quarters D on the first circle of officer’s houses on base. Quarters D was (and probably still is) a small, two-bedroom wooden frame house, a short bicycle ride from the hospital. The houses are separated by mighty Oak trees decorated with Spanish moss and our back windows looked out on the Beaufort River, about 50 or more yards away.

It was a cool, dry day with temperatures in the mid-50s. An hour or two before the party was scheduled to start a calamity struck: the electricity on the entire base went out for reasons we never determined. The hospital’s emergency generator kicked in alleviating any concern about patients, but it didn’t serve the rest of the base. We had electric warming plates for some of the hors d’oeuvres that we thought we wouldn’t be able to use but most things were heated on the gas stove. Although the refrigerator was off we were confident things would stay cold for at least a few hours. Most of the sodas and beers would be in an ice container. We couldn’t make coffee, but that was not vital.

But the sun was setting – it was winter and the days were already short – and it was quickly getting dark.

Candles! What could be better to bring on the aura of 1770? We already had a good supply of our own (in hurricane season the electric power went off quite often) as well as a couple of hurricane lamps and I scurried over to our neighbors who had more than enough to lend us. Soon our house was aglow in a soft buttery yellow glow light emanating from wax tapers of various sizes and shapes.

Perfect for a birthday party celebrating someone born in 1770.

But what about the music? How could we celebrate Beethoven’s birthday without listening to his music?

A few minutes before our first guests arrived the electric power was restored! We decided, however, to keep the candles to maintain the 18th century atmosphere in order to better appreciate the music as well as the mood Beethoven must have enjoyed while sipping wine or beer. Now, fifty years later, I can’t recall how many people we invited but everyone came and there was more than enough of Kate’s delicious food.

In the 50 years since 1970 we have had many Beethoven birthday parties, both in Teaneck, New Jersey, where we settled after Beaufort, and in Beverly Hills, where we now live. We were planning on celebrating again this year but, of course, COVID made that impossible. We, and our potential guests, have gotten older over the years, and there are more years between now and Beethoven’s birth but, of course, the music is timeless. This year we will remain sequestered inside, listening to some of the piano sonatas, quartets and symphonies and, as usual, will toast our long-time beloved friend, Ludwig van Beethoven.

What if you haven’t listened to that much of Beethoven’s music over the years and want to re-introduce yourself?

Where to start? Recently, the New York Times asked a number of people to suggest Beethoven pieces for those not completely family with his work. This article – https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/02/arts/music/five-minutes-classical-music-beethoven.html?action=click&module=Editors%20Picks&pgtype=Homepage – includes samples from some wondrous pieces of music. Try them all. You won’t regret it.

For complete works, you might want to try Idagio.com, a free music library. It doesn’t have all of the very best recordings, but it has enough music to keep you busy for a long time. It has more than 5,000 Beethoven recordings you can sample, ten times as many as any other composers it lists. If you haven’t listened to that much Beethoven over the years, start with the very short, light-hearted, and wonderful witty piano piece, “Rage Over a Lost Penny” (https://app.idagio.com/works/484011), here recorded by Alfred Brendel, is worth trying. Another highly accessible Beethoven piece is the Symphony #5, of course, whose opening four notes (da-da-da-dum) are recognizable around the world. But listen to the whole piece as Beethoven summons you to hear his grief and despair before the thrilling finale which is overflowing with energy and hope. Symphony #7 is one of the most beautiful musical works ever written, especially the second movement, which can also be found in the New York Times link above. The ‘Ode to Joy’ theme of the Symphony #9 is also very well known, and the entire symphony is magnificent, almost supernaturally thrilling and inspirational. The Violin Concerto is marvelous. Etc, etc, etc. If you have an Echo or similar device you can just say “Alexa, play Beethoven’s piano sonatas by Arthur Schnabel” and you will thrill to exquisite music, exquisitely played. You can find Beethoven performances on YouTube as well as Apple music and other streaming programs. There are even a handful of radio stations completely devoted to Beethoven:

Our wonderful Los Angeles classical music station, KUSC, will also play lots of Beethoven today: https://www.kusc.org/radio/

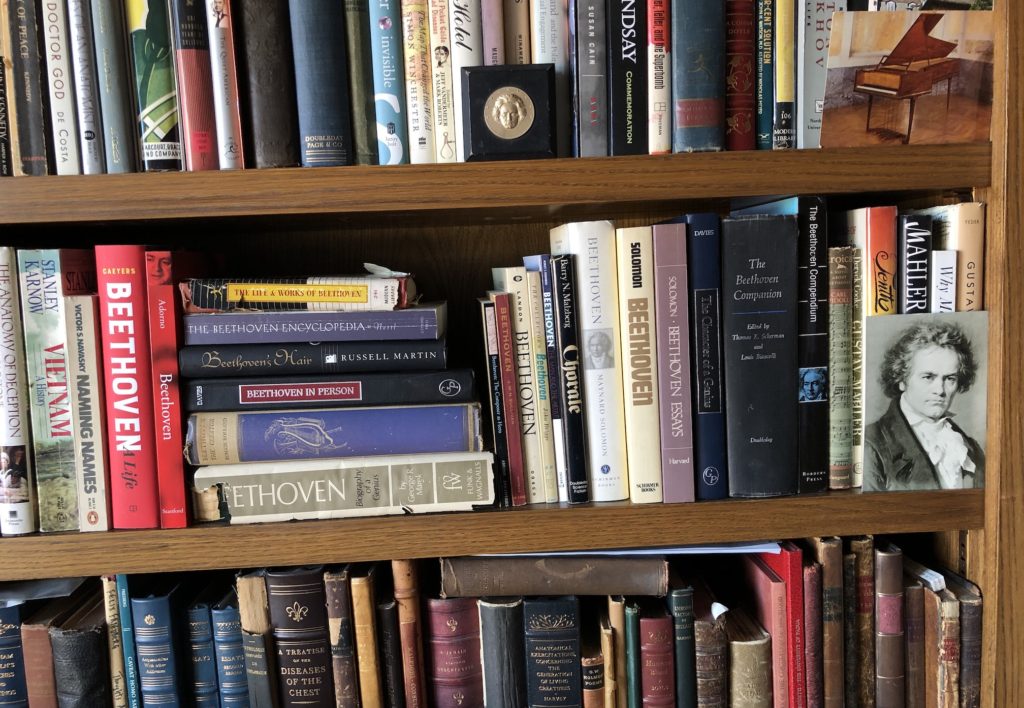

As is obvious, I love the music of Beethoven. Dozens of books, fiction as well as non-fiction, have been written about  him and continue to be written. One of the greatest novels ever written, Jean-Christophe, written in 1904 by Romain Rolland and for which he received the Nobel Prize, is loosely based on Beethoven’s life, written after his biography of Beethoven. Rolland described his protagonist as “Beethoven in the modern world.” I also love the true story of Beethoven, the greatest composer who, while still young, was afflicted with rapidly developing deafness and yet wrote some of the most marvelous and extraordinary music ever composed. He was completely deaf when he wrote the Symphony #9 and many dozens of other incomparable musical compositions. The last five Quartets. The last five piano sonatas. The Missa Solemnis. How is that possible? I suppose it is not possible, except that Beethoven did so. I also love the character of Beethoven, the man who revolutionized music and also exulted in the democratic revolutions of his time. Who poured out his despair and anguish, his disappointments at love, as well as his unending optimism and hope. Written letters and notes that survive him attest to his suffering and his pain, his loneliness, but especially his faith, his courage, and his belief in mankind. The story of his third symphony, now well known as “Eroica”, (Heroic), is worthy of retelling. Originally, dedicated to Napoleon Bonaparte because of his historic efforts for liberty and equality early in his career, the first manuscript shows where Beethoven erased his name,

him and continue to be written. One of the greatest novels ever written, Jean-Christophe, written in 1904 by Romain Rolland and for which he received the Nobel Prize, is loosely based on Beethoven’s life, written after his biography of Beethoven. Rolland described his protagonist as “Beethoven in the modern world.” I also love the true story of Beethoven, the greatest composer who, while still young, was afflicted with rapidly developing deafness and yet wrote some of the most marvelous and extraordinary music ever composed. He was completely deaf when he wrote the Symphony #9 and many dozens of other incomparable musical compositions. The last five Quartets. The last five piano sonatas. The Missa Solemnis. How is that possible? I suppose it is not possible, except that Beethoven did so. I also love the character of Beethoven, the man who revolutionized music and also exulted in the democratic revolutions of his time. Who poured out his despair and anguish, his disappointments at love, as well as his unending optimism and hope. Written letters and notes that survive him attest to his suffering and his pain, his loneliness, but especially his faith, his courage, and his belief in mankind. The story of his third symphony, now well known as “Eroica”, (Heroic), is worthy of retelling. Originally, dedicated to Napoleon Bonaparte because of his historic efforts for liberty and equality early in his career, the first manuscript shows where Beethoven erased his name,  tearing through the sheet, when he heard that Napoleon became a dictator, proclaiming himself Emperor. You can also see here the French influence as Beethoven signed his name “Louis” instead of “Ludwig.”

tearing through the sheet, when he heard that Napoleon became a dictator, proclaiming himself Emperor. You can also see here the French influence as Beethoven signed his name “Louis” instead of “Ludwig.”

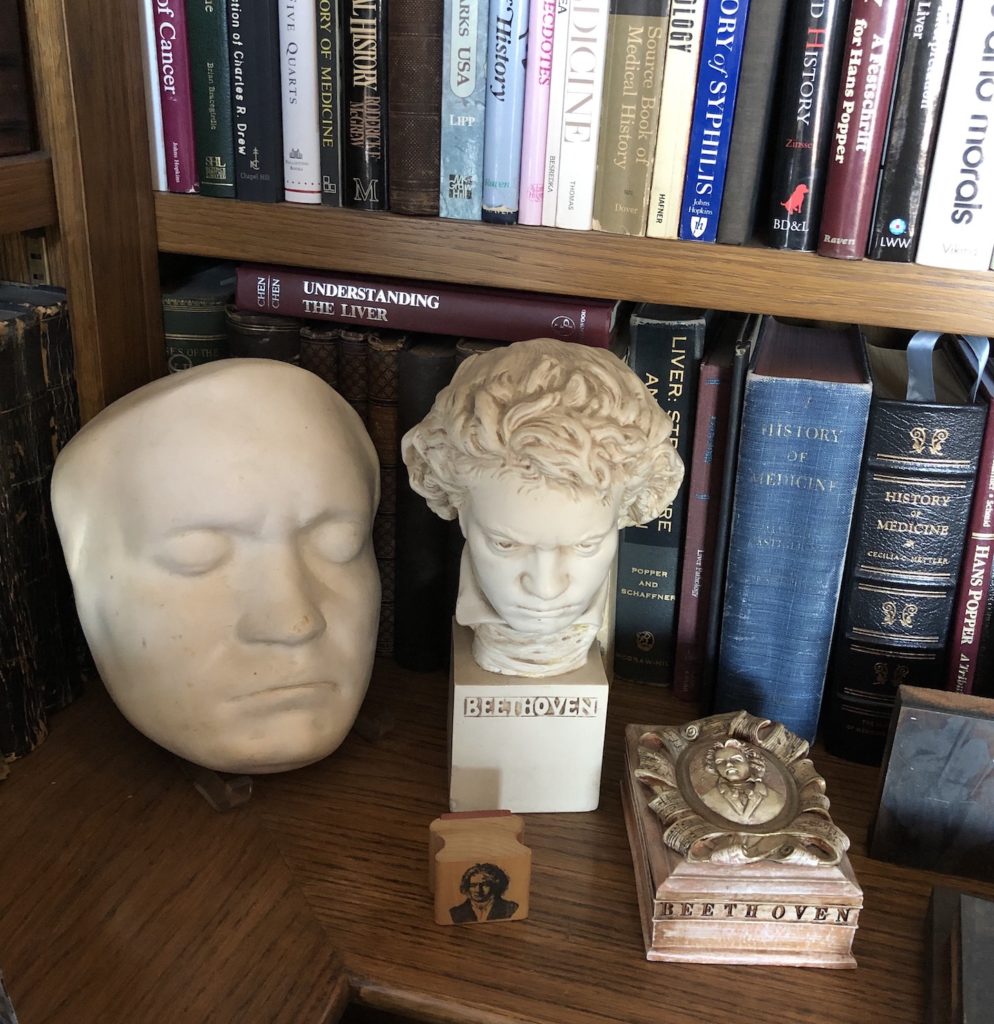

Beethovens heart and soul are all there, in the music. Listen to the late string quartets and you will know of anguish and suffering, but also hope and redemption. He was a true pioneer, shepherding the transition of music from the Classical style, full of form, poise and balance, to the Romantic style, characterized by emotion and impact. All of the greatest composers who followed him were shaped by his creations, many of them haunted in their efforts to match his brilliance and plagued by their understanding that they could never surpass him. Many years ago we were walking through a flea market on Columbus Avenue and 77th Street in Manhattan and there, half-buried among various bric-à-brac, was a plaster copy of a Beethoven mask made two years before he died. I asked how much it was. The vendor replied, “Ten bucks. Do  you know who that is?” I whipped out a ten-dollar bill and said, “Yes. Yes, I do,” as he bubble-wrapped my treasure. Beethoven continues to, happily, haunt me.

you know who that is?” I whipped out a ten-dollar bill and said, “Yes. Yes, I do,” as he bubble-wrapped my treasure. Beethoven continues to, happily, haunt me.

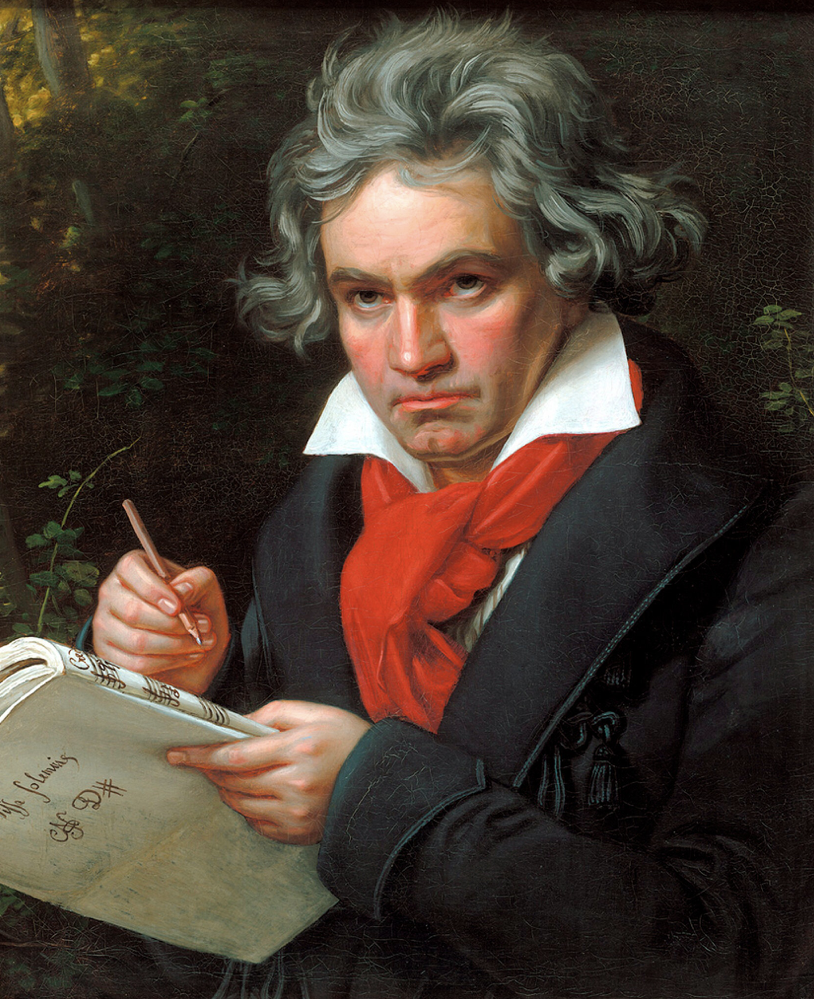

The portrait at the top of this essay, painted in 1820, seven years before Beethoven’s death, by Joseph Karl Stieler, is the only one for which Beethoven ever posed and shows him writing the Missa Solemnis. You can see how well it depicts him by comparing it to the mask.

Beethoven is not always easy to understand. But try listening to a given piece more than once. You will gain increasing familiarity with his great and unique artistry and you will find the experience very much like investing in a stock that continuously doubles. Before you know it, you are wealthier than ever imaginable.

This year, in celebration of Beethoven’s 250th birthday, join me in listening to his music and raising a glass of wine or beer or even water in memory of this extraordinary and inimitable genius who changed music forever, who changed the world forever..

December 16, 2020 at 2:12 am

The tourist board of Bewfot appreciates this ! And so do Louis (Ludwig) and I.

December 16, 2020 at 6:50 am

Stephen – you’re ability to motivate your readers to your enthusiasms is incredible. Don’t stop sending your missives!

I cycle through my classical recordings (arranged alphabetically by composer) while doodling in my home office and coincidentally just finished Bach and headed into Beethoven. Didn’t realize it was his birthday but I’m delighted to join the celebration!

December 16, 2020 at 2:23 pm

Perhaps you con join us next year for the 251st celebration.

December 16, 2020 at 7:42 am

Hi Dr. Geller,

Thanks as always for sharing your thoughts via your essays. I’ve learned alot from them over the years. Just last night my son was trying to play a few notes from Ode to Joy on the clarinet (which he picked up as his 4th grade instrument this year). Also on another “note,” I really enjoyed your essay on the watch!

Happy Holidays.

Amir

December 16, 2020 at 2:26 pm

Amir, thank you for the comments. Good for your son. It must be wonderful to hear him play. There is a fun coloring book about Beethoven you can get from Amazon he might not be too old to enjoy. Best wishes. Stay safe!

December 16, 2020 at 2:16 pm

Brilliant

Thanks for sharing

Raising a glass of cold beer

Fernando

December 16, 2020 at 4:17 pm

Thanks so much. As I was reading your article I was taking a zoom class on music and we were listening to Beethoven and watching some amazing concerts. What a lovely coincidence. I enjoyed your writing very much and particularly share your love of the music.