Beethoven!

The name is immediately recognizable across the world, even by people who have never listened to classical music.

For some, the name will sound in their head as something like: da-da-da-dum.

For others, it will recall the ‘Ode to Joy’ chorus of the 9th symphony.

A few will painfully recall struggling to master ‘Für Elise’ at the piano. Or ‘The Moonlight Sonata.’

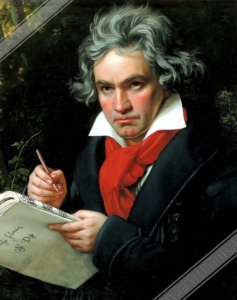

For still others, it will be the recalled image of a man with tousled, gray-hair and a slight scowl.

Some, more familiar with his story, will know of his symphonies, his piano sonatas, his unmatched concertos for piano and violin.

They’ll probably know of his deafness and, even more, of his ability to compose some of the greatest music ever written when he couldn’t hear anything.

A few will know he was a student of Haydn and a brilliant and renowned pianist.

Many who who think of his name will unconsciously add that exclamation point, as I did at the beginning of this blog, something that won’t be attached to Bach or Mozart or Brahms or any other musician.

Very few are aware that he was also a celebrated conductor. This blog is about Beethoven, the Conductor.

In my senior year at Brooklyn College, 1958-59, as I struggled to become a pre-med rather than a liberal arts student, I took mostly science courses. One of the ‘lighter’ courses I took was “The Music of Beethoven,” taught by Benjamin Grosbayne, who was Chairman of the Music Department. A Harvard graduate, Grosbayne studied conducting with some of the leading conductors of his time, including Pierre Monteux and Felix Weingarten and previously led orchestras in Paris, Brussels, Helsinki and other great cities. In the waning days of silent movies, he was a traveling conductor for Paramount and D.W. Griffith films. He wrote a leading textbook about conducting and, in 1930, was a music reporter and critic for the New York Times. I am sorry to say I knew nothing of this until I read his 1976 obituary. I did know of his great enthusiasm for Sherlock Holmes—he was a member of the Baker Street Irregulars—as well as his fondness for three-dimensional chess.

Grosbayne required a term-paper and, for reasons I do not recall, I decided to write about “Beethoven, the Conductor.” I was flattered when Professor Grosbayne told me he knew very little about this aspect of Beethoven’s life and asked for a copy of the bibliography. I was slightly annoyed, as 20-year-olds can be, when he questioned my ability to read some of the articles in German, since I had previously spent three painful semesters with Frau Professor Zollinger struggling with that challenging language.

This blog is partly based on that term paper written 63 years ago.

Beethoven was a virtuoso pianist by the time he reached his teen years. He also performed credibly, if not brilliantly, on the organ, the violin and the viola. Indeed, it was as a violist that served as a member of an operatic orchestra for four years, beginning in 1788 when he was eighteen. As Beethoven came into maturity, the orchestra was transforming from a large chamber music group to the full orchestra we know today. The piano ceased to be a part and the strings, particularly the violin, became the principal carriers of the melodic line, their place and number in the orchestra becoming relatively standardized. At the same time the brass and the woodwinds, as well as percussion instruments, took their place as the modern orchestra had its beginning.

Beethoven played a significant role in the development of the orchestra. He did not add to the array of instruments but helped balance the relations of the various orchestral players, giving them full voice in bringing forth the power and expression of the ensemble.

Beethoven may have been the greatest pianist of his time. He was also a well-known, albeit not as renowned, conductor. Generally, he conducted programs largely of his own work, usually from the pianoforte bench, as was the custom of the time. One observer testified to his abilities when he was young when describing the first half of a program, under Beethoven’s direction, as “very beautiful, but after he retired (from the podium) they became so poor …” As early as 1805, when his hearing was beginning to fail, his conducting was described as “… gestures …” that could lead the orchestra “astray.” Indeed, those reporting on his technique as a conductor generally regarded it as poor. He was likened to a whirlwind: “Our master could not be presented as a model in respect to conducting, and the orchestra always had to take care in order not to be led astray by its mentor; for he … was ceaselessly occupied by manifold gesticulations to indicate the desired expression. He used to suggest a dimuendo [a decrease in loudness] by crouching down more and more, and at a pianissimo [a passage marked to be played very softly] he would almost creep under the desk. When the volume of sound grew, he rose up … as if out of a stage-trap, and with the entrance of the power of the band, he would upon the tips of his toes almost as big as a giant, and waving his arms, seemed about to soar upwards to the skies. Everything about him was active … and the man was comparable to a perpetuum mobile.”

Still, in those early years of hearing failure, another witness wrote that, despite his “violently eccentric conduction” and the “wild contortions of his body,” he was usually successful.

There are many reports about Beethoven’s overactive technique and many tragi-comic incidents were associated with his performances. In many instances, particularly as Beethoven’s hearing became increasingly impaired, the concertmaster would serve as guide for the orchestra. Ignaz von Seyfried (1776-1841), a Viennese musician, composer and conductor, has recounted many stories about Beethoven. In one, he describes a concert where Beethoven was playing a new piano composition of his own. “… at the beginning of the first tutti [a passage to be played with all instruments together], forgetting he was (just) the soloist, he jumped up and began to conduct in his usual style. At the first sforzando [a sudden, marked emphasis], he flung out his arms so violently as to extinguish both the lights (candles) on the piano desk, the audience laughed and he was so put out by the disturbance that he made the orchestra leave off and recommence (from the beginning).” Seyfried sent for two choir boys to stand by Beethoven and hold the candles; one of them unsuspectingly drew near to look over the pianoforte part; when the fatal sforzando arrived, he received such a smart slap, that he dropped his light in terror; the other boy, more cautious than his companion … by suddenly stooping, escaped the blow. If the audience had laughed before, they now burst into a truly Bacchanalian roar. This threw Beethoven into such a rage that he broke half a dozen (piano) strings (playing) the first chords of the solo. All the efforts to restore quietness and attention were for the time fruitless. The first allegro [at a brisk, lively tempo] of the concerto was, therefore, quite lost.”

The best known and most poignant story about Beethoven’s conducting concerns the 1824 performance of the magnificent Symphony #9. “There had been but two rehearsals … naturally the performance left much to be desired. But Beethoven heard neither its defects not its beauties. He stood in the center of the orchestra with his back to the audience, following the proceedings in the score. The word ‘following’ must be taken literally. For a lady named Grebner, who, at the age of seventeen, sang in that historic chorus, said …” three quarters of a century later, that “ … although Beethoven appeared to follow the score with his eyes, at the end of each movement, he turned several pages altogether.” Another witness, the pianist Sigismund Thalberg (1812-1871), who came to Vienna for advanced studies at the age of 10 and who is regarded, along with Liszt, as one of the greatest pianists of all time, recalled that the choir and orchestra were directed to watch Beethoven but to “pay not the slightest attention to the beating of the time. Tumultuous applause broke out after the scherzo [the heading for a movement in a symphony or sonata]. But Beethoven stood utterly deaf to it, fumbling with his score. Then one of the singers … pulled his sleeve and pointed to the rapturous audience. When he turned and bowed, there were few dry eyes in the house.”

Speculation is always somewhere between risky and wrong and is an almost forbidden activity for a pathologist. Some have speculated that the incomparable music Beethoven created—many say the most glorious music ever written—would not have come to be if he had not lost hearing and, instead, had continued, as others did, to foster a career as a conductor.

I believe that.

The world is better by far because of Beethoven’s affliction. Who can tell you the names of the great conductors of the 19th Century? Only scholars devoted to the history of music and very few of them.

Who can tell you a least something about Beethoven? The list of those who cannot is very short.

A previous blog about Beethoven was written in 2020 at the time of the 250th anniversary of his birth:

https://stephenageller.com/2020/12/16/beethovens-250th-a-half-century-of-celebrations/

October 1, 2022 at 3:03 pm

“Overactive technique.” Sounds like Leonard Bernstein.

October 1, 2022 at 3:07 pm

Koussevitzky started conducting in 1886, I think.

October 1, 2022 at 3:17 pm

Dr Geller

Thanks for continuing to teach.

Remember I wrote you about the true story of Moonlight serenade?

October 1, 2022 at 3:49 pm

Thanks very much Steve.

Your love of Beethoven and quality of research and prose are wonderful and I am very grateful.

Love

Milt

October 2, 2022 at 5:05 pm

As usual, a great blog! Geller’s knowledge and writing is tremendous.

Beethoven would be proud.