I have always loved listening to jazz pianists.

The first jazz pianist I ever heard was Erroll Garner (1921-1977) when he gave a concert at Brooklyn College in thelate 50s and he has long been a favorite. I also love to listen to Oscar Peterson (1925-2007) as well as Art Tatum (1909-1956), who, in many ways, led the way for Garner, Peterson, and others.

For most of the last two decades, whenever I was at our East 49th Street apartment, I would try to have dinner at the wonderful, now shuttered, La Méditerranée restaurant on 2nd Avenue and East 50th. Two steps down and Kate  and I would find ourselves in a warm and cozy bistro, welcomed by the always gracious, smiling owner and host, Ernesto Morel. He would escort us past the bar and the large photograph of Van Johnson, the actor and Ernesto’s friend, to a table close to the piano. The food was always outstanding and the wines delicious; Mario, the waiter,

and I would find ourselves in a warm and cozy bistro, welcomed by the always gracious, smiling owner and host, Ernesto Morel. He would escort us past the bar and the large photograph of Van Johnson, the actor and Ernesto’s friend, to a table close to the piano. The food was always outstanding and the wines delicious; Mario, the waiter,

often topped off our delicious Côte du Rhone. I mostly went there, however, to hear Harold John (Harold Giminez) who sat at that keyboard for the better part of 20 years and who was one of the best jazz pianists I have ever heard. When he was young he played with Piaf, George Trenet, Chevalier and others in post-war Paris. Harold had a vast repertoire and was always ready to learn a new piece. Every now and then one of his loyal fans would break into song to accompany him. His rendition of New York, New York rivalled Sinatra’s. There was a great feeling of warmth when he played I Love Paris (one of his favorites) and a grand parade seemed to march by with his Alexander’s Marching Band. We last heard him—he was 92 then—some weeks before the start of the COVID isolation and I have not been able to locate him since. One of my favorite CDs is one that Harold gave me with him playing a medley of marvelous songs. The Evita theme, as he plays it, can break your heart. He resurrects the old Mario Lanza song, Be My Love, with a new tenderness. His version of Non, je ne regrette rien or La vie en rose can transport you back to a Paris basement cabaret and can elicit tears. I never tire of hearing him. The next time you visit, remind me and I will play that marvelous CD for you.

Recently, and to my great surprise, I heard another great—perhaps the greatest—jazz pianist: Yuga Wang.  Not known as a frequenter of bistros, cabarets and saloons she is typically seen in venues such as New York’s Carnegie Hall or London’s Wigmore Hall. She usually plays Beethoven and Brahms instead of Cole Porter and Irving Berlin.

Not known as a frequenter of bistros, cabarets and saloons she is typically seen in venues such as New York’s Carnegie Hall or London’s Wigmore Hall. She usually plays Beethoven and Brahms instead of Cole Porter and Irving Berlin.

When I was growing up, in the 40s and 50s, the two greatest classical pianists definitely did not look like Yuga Wang. They were Artur Rubenstein (1887-1982) and Vladimir Horowitz (1903-1989). My grandfather, Louis Podberesky, who loved music, favored Rubenstein but I was never sure if it was because he thought him the

better pianist or because he was convinced Rubenstein emigrated from Poland rather than Russia. Grandpa thought Horowitz was a Russian and he was not fond of Russia (another story perhaps to be told in some future blog). However, Horowitz was actually born in Kiev (Kyiv) which is in today’s Ukraine, and Rubenstein was from Lódz, which was also part of the Russian Empire at that time. To my grandfather, as well as to Rubenstein himself, he was Polish. My grandfather was from Vilna, in what was then Poland. Vilna is east of Vilnius, Lithuania, in what is now Belarus. Grandpa graduated from the great University of Vilnius.

Many years later, when my ear became a bit more sophisticated, I could appreciate the differences in the playing of Rubenstein and that of Horowitz and could also understand why there never was a “best.” Both are correctly recognized today as among the greatest pianists of all time.

Horowitz often seemed stern and was referred to as “difficult.” When he played his face was usually immobile, reflecting intense concentration. He suffered from depression and periodically underwent electroshock therapy and was also treated with anti-depressant medications. In the 80s he withdrew from performing for a number of years. Although married to Wanda Toscanini, daughter of the great conductor, Arturo, many believe he was also homosexual, in a time when that couldn’t be disclosed. Horowitz lived close to The Mount Sinai Hospital, in New York’s upper East side and once, when my daughter—she was quite young then—and I were resting on a bench outside a bookstore on Madison Avenue in the East 90s, the great Horowitz walked by us. I insisted we stand for him and was pleased when he nodded to us.

Rubenstein, in contrast, was ebullient. Chopin was his greatest love and and, as a pianist of Chopin’s work, he was

without peer. He was considered a “ladies man” and may have had at least two children with women to whom he was not married.

When we lived in Beaufort, South Carolina, we almost met Rubenstein. He was giving a recital in Charleston. One of our friends, Harriet Keyserling (1922-2010), learned we were going and asked if she could drive with us (Charleston is approximately an hour from Beaufort) and, she added, would we accompany her to the reception after the concert for ‘Artur?’ Harriet, a New Yorker, married the Beaufort native, Herbert Keyserling (1915-2000), when he was working at NYU while awaiting being called to serve in World War II; he would eventually be one of those landing at Guadalcanal and was awarded a Silver Star, one of the nation’s highest military honors. Herb, a general practitioner, was one of the most skilled and compassionate doctors I have ever known. His memoir (Keyserling, Herbert. Doctor K – A Personal Memoir, self-published, 1999; available on Amazon) is interesting, entertaining and witty. His obituary notice, (https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5802c4d9414fb5e45ce4dc44/t/599993f11e5b6cc138d0ac59/1503237106393/Keyserling%2C+Herbert.pdf – only this first sections is available), written by his friend, the author and Beaufort native, Pat Conroy, depicts him well.

It is hard to convey the excitement I felt knowing I would meet the great Rubenstein, whose name was so familiar to me from childhood. Alas, however, Harriet developed a cold the day before the concert and could not attend. We, of course, went without her. Rubenstein was magnificent but we never got to meet him.

Harriet was, to use the trite, but completely apt, term, “a force of nature.” She was the cultural center of Beaufort. Sundays in her home were spent listening to a young musician from the university or talking with Pat Conroy, who had just published his first book, or watching an Ingmar Bergman film (the local theaters seemed to vary between John Wayne and Elvis Presley movies). Friends with leaders of the Democratic Party, including the Kennedys and Adlai Stevenson, Harriet would herself go on to be a three-term State Senator. Her autobiography (Keyserling, Harriet. Against the Tide, University of South Carolina Press, 1998) is a fascinating read.

But we wander from our story …

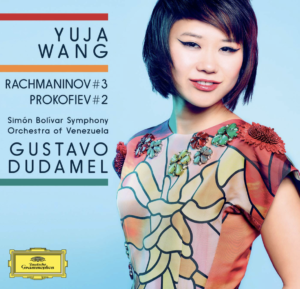

On Friday, February 10, a week ago, we went to hear Yuga Wang play the Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra in Disney Hall, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel. This was just a few days after the announcement that Dudamel was named to be the new conductor of the New York Philharmonic, the oldest symphony orchestra in the United States, filling the position once held by Gustav Mahler, Arturo Toscanini, Leonard Bernstein, Zubin Mehta and others.

The Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Opus 43, is a single-movement piece but, otherwise, is a piano concerto. It usually is played in about 27 minutes. It was premiered, with Rachmaninoff at the keyboard, in 1934, at the Lyric Opera House in Baltimore, Maryland with Leopold Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra. Later that year they recorded the piece. There was a second recording in England in 1938 and then the piece was almost unheard of for approximately 20 years. The second world war may have been a factor in this but there also may have been a cooling to Rachmaninoff’s works in the late 1930s. Then, in 1951, William Kappell (1922-1953) recorded Rhapsody,

the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto #3, and other Rachmaninoff compositions, to great acclaim; the recordings were exceedingly popular with the public and many vinyl records were sold. Since then Rachmaninoff’s work has been a mainstay of the concert repertoire. Kappell, an extraordinarily gifted and handsome American pianist, seemed destined to bring young people back into concert halls until, returning from an international tour, the plane bringing him from Australia crashed in a dense fog surrounding the San Francisco airport, killing everyone on board, including the 31-year old Kappell. With YouTube you can hear many of his performances and see the only video of him playing.

Wang’s playing is marvelous. In some ways, it is a revelation. She is technically amazing but the shading she brings to her playing is what makes her special. There is a slow, wonderfully melodic segment that is heard in the first few seconds of the piece, repeated at about 7 minutes and then again repeated about sixteen minutes into the first movement. It is one of the most beautiful melodies in all of music. When Yuga Wang played it, she captured the audience and orchestra members alike. The acoustics of Walt Disney Hall are extraordinary and each note seemed the purest crystal diffracting light into a rainbow of sound.

Thursday evening, we again heard Yuga Wang, this time playing the Rachmaninoff Third Symphony. The “Rach 3” is magnificent and particularly demanding, considered one of the most difficult piano pieces to play. The Rubenstein and Horowitz performances are on YouTube; the Horowitz is, I think, superior.

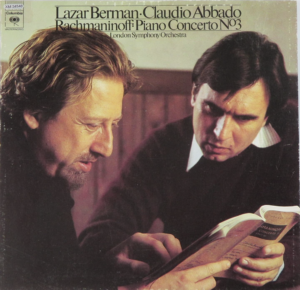

The Rach 3 is one of my favorites and I have listened to many recorded performances. The best Rach 3 recording I know is by Lazar Berman (1930-2005) with the London Symphony led by Claudio Abbado. Berman was one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century but was only rarely heard in the United States.

Here is a link to a free Amazon streaming service if you want to hear the Berman Rach 3 recording (it’s the first piece on the stream), as well as a long list of pieces by Liszt, Tchaikowsky, Chopin and Beethoven brilliantly played: https://www.amazon.com/music/player/albums/B01FTGDG6O?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1676235223&sr=1-1. The performance of the Beethoven Piano Sonata #23 (“Appassionata”) is one of the best you will ever hear.

piece on the stream), as well as a long list of pieces by Liszt, Tchaikowsky, Chopin and Beethoven brilliantly played: https://www.amazon.com/music/player/albums/B01FTGDG6O?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1676235223&sr=1-1. The performance of the Beethoven Piano Sonata #23 (“Appassionata”) is one of the best you will ever hear.

I was fortunate enough to have heard Berman at Carnegie Hall twice. At one time I subscribed to the BBC music magazine and saw an announcement of his first trip to America and of his concert at Carnegie. I immediately ordered tickets. For a good part of his career, Berman was not allowed to leave Russia, despite international acclaim designating him as “the world’s greatest living pianist.” He was a Jew at a time when the USSR was blatantly anti-semitic and, to compound this, he had married a French woman was thus, in those highly repressive days of the USSR, also a traitor. He was permitted to travel in the late 1970s and performed with such celebrated conductors as Abbado, Guilini, Karajan, Bernstein and Barenboim. It seemed his travels would no longer be restricted until 1980 when banned American books were found in his luggage. In the 1990s he was allowed to resume traveling and he moved to Florence, Italy where he lived the last 15 years of his life. The second time I heard him was at the time of the height of the international movement to try to convince the USSR to let Jews migrate to Israel and other countries and Berman was again at Carnegie. Inexpicably, two sets of activists with coarsely blaring klaxon horns, shouting “Free the Russian Jews,” twice interrupted his performance. They certainly disturbed those of us in the audience—Berman was a Jew—but Berman’s concentration was complete and his performance marvelous.

Back to Rachmaninoff …

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) was a great Russian-American composer, brilliant pianist and some-times  conductor. Born into Russian aristocracy, he was one of the last students of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Rachmaninoff and his family left the USSR after the 1917 Russian revolution, settling, at first, in New York and, briefly, in Beverly Hills, where he died from widespread melanoma. He is buried in Kensico cemetery in Westchester County, New

conductor. Born into Russian aristocracy, he was one of the last students of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Rachmaninoff and his family left the USSR after the 1917 Russian revolution, settling, at first, in New York and, briefly, in Beverly Hills, where he died from widespread melanoma. He is buried in Kensico cemetery in Westchester County, New  York, as are other luminaries, including the opera stars Robert Merrill and Beverly Sills, the writers Paddy Chayefsky and Ayn Rand, Lou Gehrig and entertainers Anne Bancroft, Danny Kaye, Tommy Dorsey and Billy Burke (the good witch Glinda from The Wizard of Oz). Kensico is

York, as are other luminaries, including the opera stars Robert Merrill and Beverly Sills, the writers Paddy Chayefsky and Ayn Rand, Lou Gehrig and entertainers Anne Bancroft, Danny Kaye, Tommy Dorsey and Billy Burke (the good witch Glinda from The Wizard of Oz). Kensico is  a peaceful and lovely resting place, reminiscent of the magnificent Paris cemetery, Cimitière du Père Lachaise, because of the beautiful sculpture.

a peaceful and lovely resting place, reminiscent of the magnificent Paris cemetery, Cimitière du Père Lachaise, because of the beautiful sculpture.

Rachmaninoff’s life was punctuated by periods in which his musical creations were not appreciated and the only way he could provide for himself was by playing the piano in recitals and with some of the leading orchestras of the world. He was considered one of best pianists of his time and his concerts were well attended. He also, early in his life, sometimes gave piano lessons but he hated this and did not do it for prolonged periods. His first symphony, written soon after Tchaikovsky died, was brutally panned by the critics. The performance was, however, marred by the fact that the conductor, Alexander Glazunov, who was also a composer, may well have been drunk.

Rachmaninoff was often depressed and was exceedingly hypercritical of himself. At one time he underwent hypnotherapy and other forms of psychological treatment with good results, after which he was able to compose the Piano Concerto #2, of which the first movement theme was used to great cinematic effect in the delightful 1955 Marilyn Monroe movie, The Seven Year Itch. That film solidified Monroe’s reputation as an important and witty motion picture star while also awakening a new interest in the music of Rachmaninoff.

Increasingly dissatisfied with turmoil in Russia, Rachmaninoff left Moscow for Dresden, Germany, in late 1906, where he was able to compose his Symphony #2. While in Dresden he agreed to tour the United States, during which time he premiered the magnificent Piano Concerto #3, first at Smith College with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and then with the New York Philharmonic, conducted by Gustav Mahler with Rachmaninoff as the soloist on both occasions. For a while it was said that only someone with huge hands, which Rachmaninoff had, could play the Rach 3, but time has clearly proven that wrong; Wang is only one of many who play the piece beautifully.

Rachmaninoff returned to Russia in 1917 and was performing a piano recital in Moscow the day the February Revolution began. He was working on revisions to his first piano concerto in October, with noisy political rallies and gunshots outside his window. He wanted to leave Russia again but had trouble obtaining visas for himself and his family until he was invited to perform ten piano recitals across Scandinavia. He used that as the excuse to obtain travel permits so they could leave the country. In 1918, he and his family came to New York. Eventually he came to live in Beverly Hills, California where he lived near Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg and Vladimir Horowitz. Rachmaninoff became close friends with Horowitz and they would often play at Rachmaninoff’s home because he had two Steinway grand pianos.

Rachmaninoff was musically conservative, more at home in the 19th rather than the 20th century. He composed relatively little in his later years. One of his last compositions was the Piano Concerto #4, composed in 1926 and modified as late as 1941. In this composition, he included some of the sensibilities of the age in which he was living, including, especially in the second movement, some jazz influences. Tomorrow, Kate and I will hear Yuga Wang play the Rach 4.

Back to Yuga Wang …

Yuga Wang has recorded the Rach 3 and a performance of her playing this piece is also available on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VHre-G8wlb4). The recorded performance is thrilling and favorably invites comparison with the many other versions, including that of Berman. Why drive to downtown Los Angeles on a Friday night, as we did? As most know, there is an electricity and excitement at a live performance that cannot be found on any recording, audio or visual, and hearing this great concerto in Disney Hall with Dudamel at the podium and Wang at the keyboard was a great privilege. It was an especially beautiful performance and the audience applauded with greater intensity than I have ever heard before, with five rounds of applause before the encore and two rounds after, lessening only after the house lights came on. She played a short piece adapted from the Glück Orfeo et Eurydice. It seemed no one in the great auditorium took a breath from the first note to the last.

Wang is a beautiful woman and often wears bright and provocative outfits with stiletto heels, for which she is  periodically criticized. The power and beauty of her playing has mostly quieted those harsh voices. I suspect most of the men in the audience don’t mind her outfits and I must acknowledge her appearance can be briefly distracting. When she hits that first key, and the glorious music fills the concert hall, none of that matters. Then, there is the music and only the music.

periodically criticized. The power and beauty of her playing has mostly quieted those harsh voices. I suspect most of the men in the audience don’t mind her outfits and I must acknowledge her appearance can be briefly distracting. When she hits that first key, and the glorious music fills the concert hall, none of that matters. Then, there is the music and only the music.

Yuga Wang is widely acknowledged to be one of the most gifted pianists of our time. It is

always tempting to name “the greatest” but rarely definitively possible. Of the younger pianists currently performing, there are three who I try to see in person whenever I can: Yuga Wang, Daniil Trifonov (his Tchaikovsky First Piano Concerto has been described as “remarkable”) and

Hélène Grimaud (her Brahms Piano Concerto #2 is superb). I don’t know which of those is “the greatest” but, at least for this week, and after thrilling at her performance of the Rhapsody and then the Piano Concerto #3, it is Yuga Wang.

Born in China in 1987, she eventually came to the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia to complete her studies. Before she was 21, she established an international reputation as an extraordinary pianist after filling in for an ailing Martha Argerich and playing the Tchaikovsky first piano concerto.

Two weeks ago, Wang played all four Rachmaninoff concertos and the Rhapsody in a marathon three-and-a-half hour performance at Carnegie Hall with the Philadelphia Orchestra, led by Yannick Nézet-Seguin, 90 years after it was first played in that same place, also by the Philadelphia but then under Leopold Stokowski’s baton. In Los Angeles and other cities in her tour, she is not repeating that remarkable feat and the concertos are played on different days.

Okay, already, what about jazz?

After she played the Rhapsody the audience would not let her leave the stage and she played an encore; Tea for Two.

Tea for Two was written in 1924 by Vincent Youmans for the musical No, No, Nanette. The song was an instant hit and the biggest success of Youmans’ career. It has been recorded many times, including a 1939 rendition by Art Tatum, for which he received a posthumous Grammy Hall of Fame award. Tatum’s version which has been the basis of most subsequent concert performances, including that of Yuga Wang, although she made her own modifications.

Of course, a part of her repertoire is Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue with its powerful jazz influences: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7jHElPJbNcc

And here is a version of Mozart’s Turkish March that she pushes into the world of jazz: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6Hbk3o8_YM

Here is a YouTube of Tea for Two, the encore we heard her play after Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PFg_EiR7rXY

Does this make her the “greatest.” I assumed that this was the only jazz piece she plays and mistakenly concluded that her repertoire would need expanding before she earns that appellation. Despite that, I felt quite  confident in saying that her playing of Tea for Two is unmatched. It is the gold standard. My daughter informed me, however, that the January 2023 issue of Pianist magazine reported that she will soon release a new album of jazz, latin and blues music. “The American Project” album, about to be released, has her playing a new concerto written by her friend, the composer and her former classmate, Teddy Abrams—currently music director of the Louisville Orchestra—and conducted by the venerable Micheal Tilson Thomas. The concerto includes jazz, latin and blues themes but I am hoping she will soon provide us with a real jazz album.

confident in saying that her playing of Tea for Two is unmatched. It is the gold standard. My daughter informed me, however, that the January 2023 issue of Pianist magazine reported that she will soon release a new album of jazz, latin and blues music. “The American Project” album, about to be released, has her playing a new concerto written by her friend, the composer and her former classmate, Teddy Abrams—currently music director of the Louisville Orchestra—and conducted by the venerable Micheal Tilson Thomas. The concerto includes jazz, latin and blues themes but I am hoping she will soon provide us with a real jazz album.

I will order the new CD with the Abrams composition soon but I’m mostly anxious to order that theoretical other CD the day it becomes available; perhaps it will also have Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern and Harold Arlen songs.

February 18, 2023 at 3:53 pm

Great story.when are you moving to New York? We will miss you.

We also Ms Wang playing the Rach 2. She was great. Marty and Lindq

February 18, 2023 at 5:07 pm

Marvelous, as always, Stephen. I, too, am a Garner fan. I first heard him at the Blue Note Cafe in Chicago in 1956.

I’ve always loved jazz-piano and have a smallish collection of CDs. I discovered Claude Bolling in the late 80’s and especially enjoy his collaboration with “greats” like Wynton Marsalis and Yo-Yo Ma, to name a few. My especial favourite is Suite No. 2 for Jazz Piano and Trio where Bolling partners with Jean Pierre Rampal.

February 18, 2023 at 5:13 pm

This blog reminds me of the strong influence that Débussy and especially Ravel had on George Gershwin. And do you think Joey Alexander will grow up one day to join your list of great jazz pianists?

February 18, 2023 at 6:03 pm

Stephen – your expertise on diverse subjects never fails to amaze me!

I enjoy classical music but listen to it mostly as background music. Rarely go to concerts and know little of the great musicians you describe so knowledgeably.

You piqued my interest regarding Yuga Wang and I watched some of her performances on YouTube including Rhapsody on a theme of Paganini and tea for two. She is spectacular!

Thanks for opening up new vistas for me!

February 19, 2023 at 9:01 am

Stephen

I always enjoy reading your blog’s never know what to expect but always new great knowledge to me.

Looking forward to seeing you and Kate in New York.

February 23, 2023 at 12:01 am

Yuja Wang is an astounding superhuman pianist, but does she play jazz? A young Californian pianist who turned her back on classical to focus solely on cutting edge jazz is Connie Han. Of course there are instances of extremely young virtuosos, for example Joey Alexander of Indonesia was a still mere child when he performed for two sitting presidents, Clinton and Obama. Some of these young guns can play faster than most of us can think.

April 15, 2023 at 7:32 pm

I am 84 years young. Looking for a way to contact Ernesto of La Meditterane Restaurant I found your lovely writing. Yes many times I enjoyed the heavenly music of Harold. Many years ago residing in my island of Puerto Rico I had to travel for business to NYC and always went to Ernesto’s Restaurant.

I now reside in Aventura Florida and would love to make contact with Ernesto. Also would like to know the whereabouts of Harold. Is any of his music recorded where can I listen?

Please if you know how I can contact Ernesto, please let me know.

Edgar Beauchamp