The Roman Emperor Hadrian (Publius Aelius Hadrianus Augustus) was born in Italica-Hispanica (modern day Seville, Spain) in 76 CE and died at his villa in Baiae, an ancient Roman town on the Gulf of Naples, in 138, at the age of 62. Hadrian is regarded as one of the five “good” emperors, along with Nerva and Trajan, who preceded him, and Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, who followed him. Marriage to Trajan’s grand-niece, Vibia Sabina, solidified Hadrian’s place as heir. Hadrian is said to have spent most of his reign traveling throughout the Roman Empire visiting the provinces, overseeing administration and maintaining and reinforcing the morale of his far-flung army. He was particularly devoted to, and supportive of, the army despite the fact that his regime was marked by relative peace. He also concerned himself with all aspects of government and the administration of justice. He was a man determined to show he was in charge throughout the empire, then the largest empire in the history of the world, encompassing most of Europe, including the south of Britain, as well as north Africa and the Middle East. The historian Edward Gibbon described Hadrian’s reign as “the period in the history of the world during which the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous …” Gibbon describes Hadrian in mixed terms: ” … an excellent prince, a ridiculous sophist, and a jealous tyrant.”

The Roman Emperor Hadrian (Publius Aelius Hadrianus Augustus) was born in Italica-Hispanica (modern day Seville, Spain) in 76 CE and died at his villa in Baiae, an ancient Roman town on the Gulf of Naples, in 138, at the age of 62. Hadrian is regarded as one of the five “good” emperors, along with Nerva and Trajan, who preceded him, and Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, who followed him. Marriage to Trajan’s grand-niece, Vibia Sabina, solidified Hadrian’s place as heir. Hadrian is said to have spent most of his reign traveling throughout the Roman Empire visiting the provinces, overseeing administration and maintaining and reinforcing the morale of his far-flung army. He was particularly devoted to, and supportive of, the army despite the fact that his regime was marked by relative peace. He also concerned himself with all aspects of government and the administration of justice. He was a man determined to show he was in charge throughout the empire, then the largest empire in the history of the world, encompassing most of Europe, including the south of Britain, as well as north Africa and the Middle East. The historian Edward Gibbon described Hadrian’s reign as “the period in the history of the world during which the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous …” Gibbon describes Hadrian in mixed terms: ” … an excellent prince, a ridiculous sophist, and a jealous tyrant.”

the best-preserved Roman buildings. Its dome is, after almost 2,000 years, still the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world. Hadrian’s Wall (Vallum Hadrian) in north Britain is

the best-preserved Roman buildings. Its dome is, after almost 2,000 years, still the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world. Hadrian’s Wall (Vallum Hadrian) in north Britain is the most famous of his structures. It marks what was then the northern boundary of the Roman Empire in Britain, once stretching from coast to coast and was designed both as a defense against invaders from the north, with an accompanying defensive ditch, and also as a means to control commercial traffic.

the most famous of his structures. It marks what was then the northern boundary of the Roman Empire in Britain, once stretching from coast to coast and was designed both as a defense against invaders from the north, with an accompanying defensive ditch, and also as a means to control commercial traffic. deeper crease extending more than halfway across the earlobe and those with the most marked change show a deep cleft extending

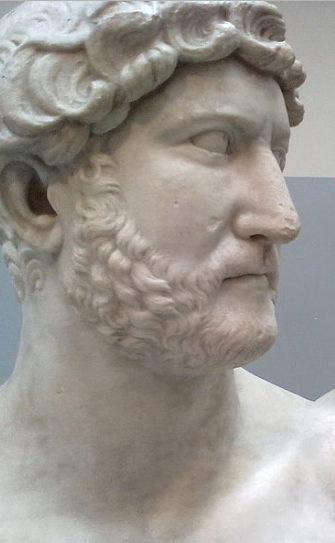

deeper crease extending more than halfway across the earlobe and those with the most marked change show a deep cleft extending  completely across the earlobe, as seen in artefacts depicting Hadrian.

completely across the earlobe, as seen in artefacts depicting Hadrian. in Wepfer’s case, distorted by fatty and fibrous plaques, as well as calcification and even ossification (bony change). There is even some widening of the lower aorta indicative of early aneurysm change. The images of Hadrian, many from when he was relatively young, suggest that he had the onset of significant atherosclerosis when he was still in his forties.

in Wepfer’s case, distorted by fatty and fibrous plaques, as well as calcification and even ossification (bony change). There is even some widening of the lower aorta indicative of early aneurysm change. The images of Hadrian, many from when he was relatively young, suggest that he had the onset of significant atherosclerosis when he was still in his forties.© 2024 Brooklyn Transplant — Powered by WordPress

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

February 22, 2018 at 5:25 pm

Fascinating! Thank you for the educational (not only about Roman history but the potential diagnostic role of the crease) essay.

February 24, 2018 at 8:59 am

Dear Dr. Geller,

Thank you for teaching us Medicine using History. Your ability to find facts in History that may explain the pathophysiology leave me always delighted.

March 6, 2019 at 9:53 am

Just wondering if a creased earlobe may have to do with large lobes being folded during sleep?

March 6, 2019 at 2:56 pm

No, it is most likely based on vascular changes.

March 6, 2019 at 3:41 pm

Thank you, Dr Geller, for the brilliant text.