In the Random House Unabridged Dictionary the fifteenth, and final, definition for “crush” is: 15. Informal. a. an intense but usually short-lived infatuation. b. the object of such an infatuation.

Diahann Carroll

Richard Rodgers (1902-1979) and Oscar Hammerstein II (1895-1960) were an enormously successful Broadway composing team, writing the music and lyrics for many shows appropriately considered among the very best ever: Oklahoma! (1943), Carousel (1945), South Pacific (1949), The King and I (1951) and The Sound of Music (1959). There were other shows (Me and Juliet, Pipe Dream, Allegro, and Flower Drum Song), a musical written specifically for film (State Fair) and another for television (Cinderella).

Rodgers and Hammerstein songs are mostly wonderfully cheerful, glittering and uplifting and they have stood the test of time well. Their shows differed, however, from most early 20th century musical comedy by deliberately and seriously addressing many moral and ethical issues, including racism, sexism and classism.

Before joining Rodgers, Hammerstein wrote two shows with Jerome Kern, including Show Boat, a landmark in theater history; Show Boat was the first Broadway musical to consider––in 1927!––racial prejudice and inter-racial marriage. Indeed, every Hammerstein show after Show Boat commented on some moral, ethical issue. Oklahoma! considers obsessive behavior, sexuality, murder and more. Carousel depicts domestic violence. South Pacific confronts racism and poignantly teaches us about its roots (“You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught”). The principal character––Ensign Nellie Forbush, a navy nurse from Little Rock––must deal with the problem of falling in love with a much older man and, especially challenging for a young woman from Arkansas in the 1940’s, accepting his racially mixed children. In that same show, Lt. Cable is in love with a Tonkinese girl but decides his prejudiced family will never accept her. The Sound of Music confronts the issue of social responsibility in the face of fascism and The King and I looks at the cruelty of autocratic rule.

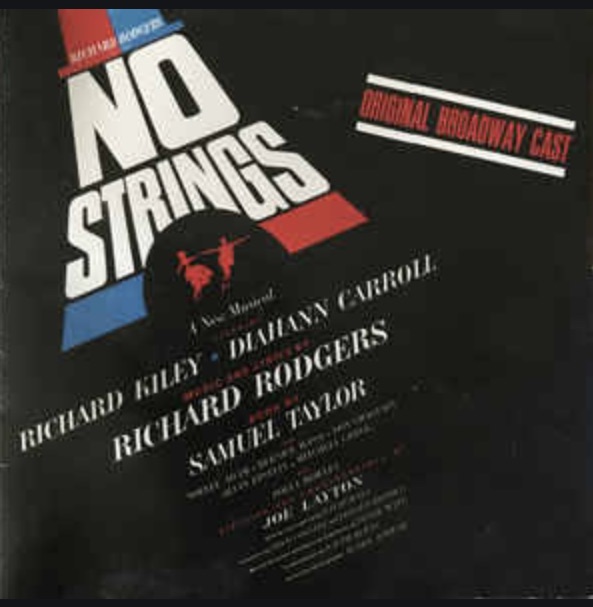

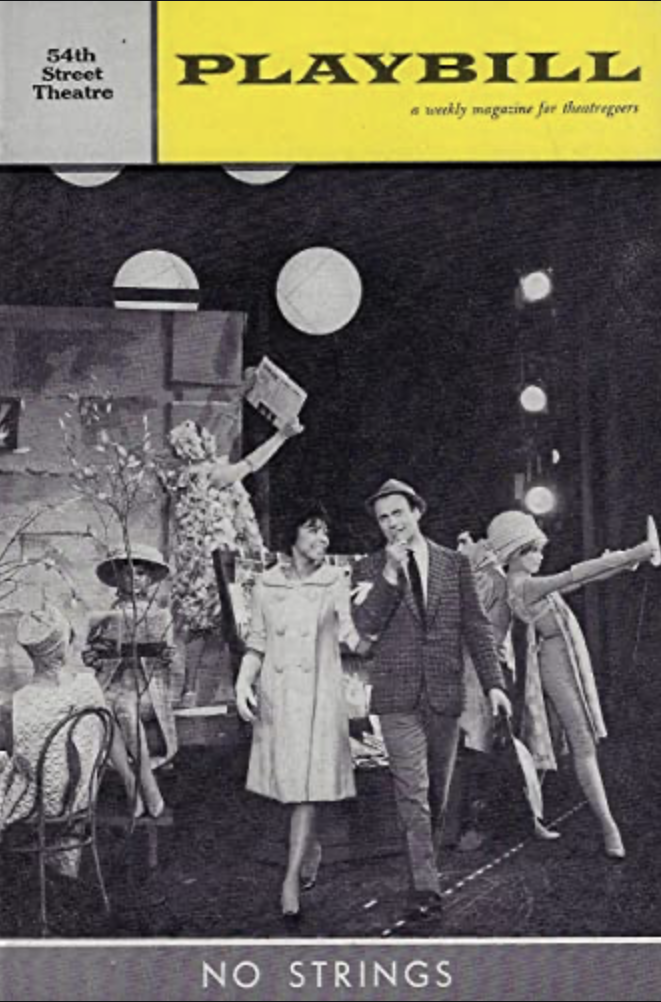

No Strings opened in March, 1962, and ran on Broadway for more than a year. It was the only Broadway show for which Richard Rodgers wrote both the music and the lyrics, and the first musical he composed after the death of his long-time collaborator, Oscar Hammerstein.

Despite the loss of Hammerstein––an outspoken, forceful proponent of American democracy, justice and tolerance––the show was a powerful, albeit indirect, statement about racial prejudice, receiving a reassuring, rave review from Howard Taubman of the New York Times: “Richard Rodgers need not have worried. He is still a magician of the musical theater.”

The show starts with a solo flute playing a hauntingly beautiful melody, “The Sweetest

The show starts with a solo flute playing a hauntingly beautiful melody, “The Sweetest  Sounds.” The female lead comes onstage from one side, singing the song’s words, and, a few lines after, the male lead, also singing, comes from the other side. Although nothing in the story mandates the casting of the principal roles, and there is no mention of race in the background book by Samuel Taylor, Rodgers deliberately selected Diahann Carroll for the role of Barbara Woodruff, a New York fashion model living in Paris. Woodruff falls deeply in love with the expatriate David Jordan, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist suffering from severe writer’s block, played by the wonderful Richard Kiley (Man of La Mancha). David wants to return home to Maine to regain his writing skills but Barbara does not see a life for herself in that rural setting and, despite their strong love, they agree to part,

Sounds.” The female lead comes onstage from one side, singing the song’s words, and, a few lines after, the male lead, also singing, comes from the other side. Although nothing in the story mandates the casting of the principal roles, and there is no mention of race in the background book by Samuel Taylor, Rodgers deliberately selected Diahann Carroll for the role of Barbara Woodruff, a New York fashion model living in Paris. Woodruff falls deeply in love with the expatriate David Jordan, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist suffering from severe writer’s block, played by the wonderful Richard Kiley (Man of La Mancha). David wants to return home to Maine to regain his writing skills but Barbara does not see a life for herself in that rural setting and, despite their strong love, they agree to part,  singing “No Strings.” Their breakup is not about skin color––which is never mentioned––but about cultural and environmental choice.

singing “No Strings.” Their breakup is not about skin color––which is never mentioned––but about cultural and environmental choice.

My wife, Kate, and I saw No Strings during our first week of marriage in June, 1962. For multiple reasons (she was a nursing school senior about to graduate and I had just completed my second year of medical school and would would start a summer externship in a few days; just as importantly, we couldn’t afford it). Instead we stayed in New York, subletting a Stuyvesant Town apartment for the summer. In that week, we saw three Broadway shows, went to a few museum and enjoyed being newlyweds.

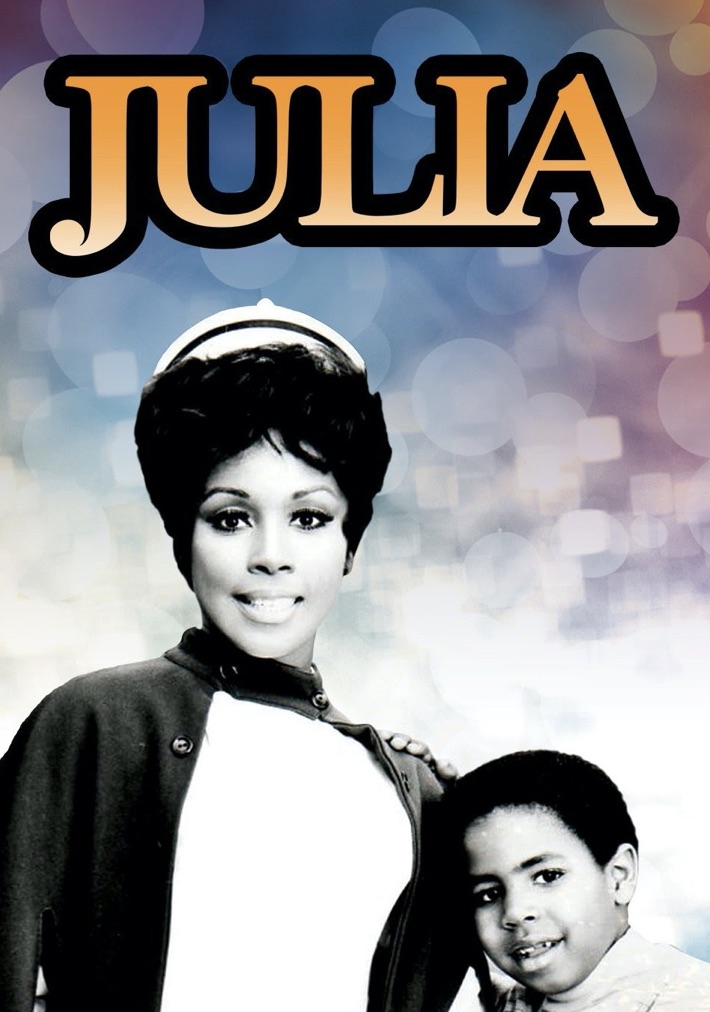

I loved No Strings and my “crush” for Diahann Carroll––who I knew by name but had never seen––began with that show. My “crush” is well known to Kate, and, in contrast to the Random House definition above, has not been terribly intense but has lasted a long time. It was reinforced fifteen years later by the television dramatic series, Julia.

Diahann Carroll played Julia Baker, a highly qualified registered nurse (R.N.) who is a widow. Recently moved from the mid-west to New York City with Corey, her young son, she is looking for a job. A Mr. Colton, the head of personnel for a large medical group, interviews her and decides, for no stated reason, that she is not suitable; Julia already learned from the clinic’s African-American handyman that she will not be acceptable because of her color. Unhappily she heads home to consider next steps.

Diahann Carroll played Julia Baker, a highly qualified registered nurse (R.N.) who is a widow. Recently moved from the mid-west to New York City with Corey, her young son, she is looking for a job. A Mr. Colton, the head of personnel for a large medical group, interviews her and decides, for no stated reason, that she is not suitable; Julia already learned from the clinic’s African-American handyman that she will not be acceptable because of her color. Unhappily she heads home to consider next steps.

However, the next day, the head of the clinic, Dr. Morton Chegley, played by Lloyd Nolan in full curmudgeon regalia, reviews her file, reads the glowing recommendations and sends her a telegram––she doesn’t have a telephone yet––asking her to call. She dashes down to the drugstore to phone and Chegley asks her to return for a second interview. A part of their phone conversation:

Julia: “But has Mr. Colton told you?”

Chegley: “Told me what?”

Julia: “I’m colored.”

Chegley: “What color are you?”

Julia: “I’m a Negro.”

Chegley: “Have you always been a Negro or are you trying to be fashionable?”

Julia was first broadcast in September, 1968, fourteen years after Brown v. Board of Education and five years after Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his “I have a dream” speech. The struggle for civil rights was/is still in progress. In April, five months before the broadcast King was murdered in Memphis and in June, three months before Julia went on air, Robert (“Bobby”) Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles. The show was not shown in much of the South. There is some controversy about the importance of Julia to the civil rights movement but I have always believed that its effect was far more positive than negative and, indeed, was one of those instances when popular entertainment helped make America a little better than it had been.

Jaguar motor car

In 1958 I was a junior at Brooklyn College. My good friend, Herb Jacobson, would be taking a trip with his Education professor, Ed Tolle, and some other students to Michigan’s northern peninsula to visit one-room school houses during the winter break at the end of January. Two cars, five students, a graduate student, and the professor–– with room for one more person. Would I like to go? Except for a trip to Washington, D.C. with my father when I was about ten I had never been further from Brooklyn than New Jersey and, with parental approval, happily accepted.

The professor had a Volkswagen “Beetle.” I had seen a few on the streets but they were distinctly uncommon. An air-cooled rear-engine automobile powered that small automobile which had been designed, at Hitler’s direction, by Ferdinand Porsche. It was only produced in significant numbers after 1945, when World War II was over. The original Beetle had four cylinders and 25 horsepower but I think the one we rode in for the Michigan trip had 30 hp.

The grad student drove a used Jaguar Mark 2 whose engine he had rebuilt.

A major snow storm began the day we left Brooklyn. I was the only person, other than Professor Tolle and the TA, who knew how to shift gears. Of course, I automatically became the relief driver.

The Jaguar at a motel, 1958

The trip was planned so that the two cars would meet at specific rest stops along I-80 for reasons that became clear as soon as we started out: the VW putt-putted its way along while the Jaguar immediately zoomed out of view. Never having even been in a VW before, much less driven one, my strong feeling was that the windshield was the front of the car, that there was no hood. I couldn’t stop leaning forward––whether I was in the driver or the passenger seat––to try and see the front of the car which sloped sharply down. Soon, the heavy snow greatly impaired visibility. The VW’s directional signals were mechanical––you reached over behind the passenger seat or  the driver’s seat to pull a lever built into the doorpost and a semaphore-like structure would snap out to inform the world of your intention to turn.

the driver’s seat to pull a lever built into the doorpost and a semaphore-like structure would snap out to inform the world of your intention to turn.

Also the VW felt almost weightless, despite being cramped, particularly when a monstrous moving van drove past in the left lane, creating a strong vacuum, moving the car quite a few inches and requiring the (terrified) driver to tightly hold the steering wheel and struggle to move back to the center of the lane. And it was cold; jackets and sweaters required!

Driving the Jaguar was something else. Whoosh. The leather seats and the roominess were luxurious, marvelously comfortable. The heater really generated heat. Sweaters were more than enough.

And there was no question that the Jag had a front end; poised proudly astride the hood was the chrome Jaguar emblem, front legs fully extended, asserting itself, urging you forward.

When we moved to Los Angeles in 1984 we only brought one car with us––a small Mazda hatchback. We visited our new accountant soon after we arrived and I asked if I should buy or lease a car. “For tax purposes, it doesn’t matter that much,” he informed us, “but the best thing to do is buy an expensive car.” He explained that there was no snow and, consequently, no salt spread on the roads. “A good car,” he told us, “will last a long time.” In addition to my long-ago college experience I had long been charmed by Jaguar cars every time I saw one in some post-war British film. I followed the accountant’s advice and drove Jaguars for twenty-five years until soaring gas prices and the advent of hybrid cars, as well as Kate’s highly principled, environmentally-minded prodding, made me go green. Contrary to Jaguar’s bad reputation I never had any significant mechanical or electrical problems in that quarter century and enjoyed every minute I was in those stylish and comfortable automobiles.

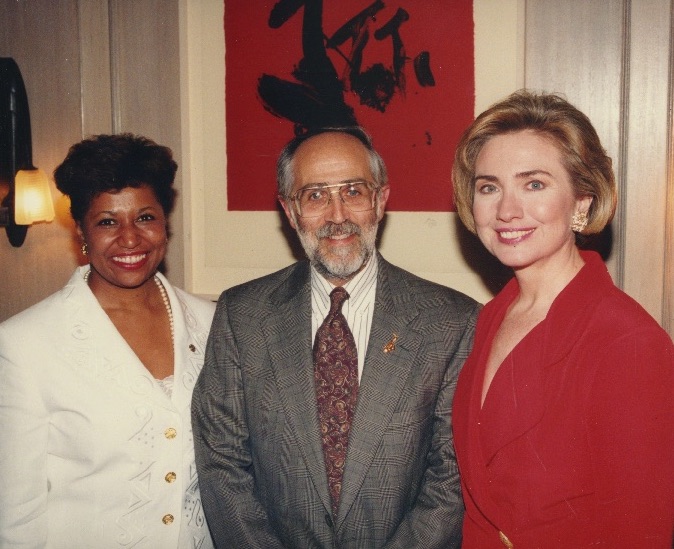

Diahann Carroll and my (temporarily missing) Jaguar

In April of 1998 Carol Mosely Braun, Senator from Illinois, was raising money for her ultimately unsuccessful re-election campaign. I received an invitation from the Democratic National Committee to attend a fund-raising reception to be held at the home of Lew Wasserman, one of the most successful, influential and powerful talent agents in Hollywood. Wasserman guided MCA for many years. Bette Davis, Jimmy Stewart and Ronald Reagan were among the people he represented. Although a staunch Democrat Wasserman helped mold Reagan’s political career and remained his lifelong friend. There’s more to Wasserman’s story, (e.g. interactions with the Chicago-based Mafia), but perhaps another day …

The Wasserman home was high in the hills of Beverly Hills––it is said that Beverly Hills has three sections; the hills where the most expensive homes are, the flats where the almost-as-expensive homes are, and the poor part, where we live, which is by no means poor.

It happened that the fund-raiser was on my birthday and it also happened that Kate would be out of town. Hillary Clinton was the guest speaker and we were great admirers. But since Kate was away and since the minimal expected contribution was one thousand dollars I decided I would not attend. Since it was my birthday and it was Hillary, Kate decided I would.

Of course, my Jaguar was perfect for such an occasion, even if only seen by the valets that parked the many luxury cars. Unfortunately, fate intervened: my Jag developed some minor mechanical problem with the sun-roof a few days before the fund-raiser and was in for repair. Instead of a chariot befitting the neighborhood and the other arriving automobiles I showed up in Kate’s unwashed, fire-engine-red Mazda RX-7 sports car with its here-and-there scrapes and scattered dents. I surrendered the key to the valet––happily no one else drove up just when I did––and went into Wasserman’s grand and, by now, crowded home.

More substantial contributions than mine allowed attendees to have a private meeting with Hillary in another room but I was quite content to wait in the very spacious living room to see her and hear her remarks. Kate and I attended the first Bill Clinton inauguration in January 1993 and I still had my saxophone pin which I again wore for this occasion. Somehow Hillary noticed the pin.

Senator Carol Moseley Braun, me with saxophone pin, Hillary Clinton

She and Senator Braun came to chat with me for quite a while, greatly amplifying my already high opinion of Hillary as an amazingly charming, witty and breath-takingly knowledgeable woman (who should have been President).

Before that, however, I noticed Diahann Carroll on the other side of the big room chatting with a group of people. My best friend had been her attorney and had even attended her wedding. I could walk over and mention his name and finally meet her. In one of those strange, infantile, semi-psychotic moments, it occurred to me I might be violating some arcane lawyer-client confidentiality ethic if I talked with her. Perhaps it was residual teenage shyness and insecurity. In any event, I missed my big chance.

Soon after talking with Hillary and Senator Braun, and not knowing anyone else, I left.

It was an uncommonly chilly, drizzly, gray day and I walked down the long path from the front door of Wasserman’s home to where the valets waited to fetch vehicles. As I handed the chief valet my car ticket I heard the click-clack of two pairs of high-heel shoes. I turned around to see Diahann Carroll and Dionne Warwick approaching. I desperately wanted to say something, anything, but my tongue was in a powerful knot.

Diahann Carroll smiled at me––that amazingly beautiful, warm smile she has––and said. “I like this kind of day, don’t you?”

“Yes,” I was able to answer, “I do. It’s a New York kind of day.”

“You’re right,” she said with great emphasis, her smile even wider and warmer than before.

I was about to step closer to continue the conversation but, just at that moment, the darn Mazda––bumps and all––arrived and I hastily mumbled something inane like, “Nice seeing you,” quickly tipped the valet more than I should have, got into the car and drove away.

Post scripts …

- The Jaguar business was founded in 1922 as the Swallow Sidecar (SS) Company. They made motorcycle sidecars before developing passenger car bodies. Jaguar first appeared in 1935 as a model name on a SS 2.5 liter sedan (“saloon”) as well as a 3.5 liter open sports car. The company name was changed to Jaguar in 1945, eventually becoming a part of British Leyland, which was nationalized in 1975. Jaguar spun off from British Leyland in 1984––the year I moved to Los Angeles and bought my first Jaguar––as an independent company until it was purchased by Ford in 1990. Ford subsequently sold Jaguar, as well as Land Rover which Ford acquired in 2000, to India’s Tata Motors. I still think of buying or leasing a Jaguar––they now have hybrid and electric models––but that does not make much sense since I live part of the year in New York, where I don’t need a car, and also because I don’t do that much driving while in Los Angeles. Our Prius manages just fine.

- I many times thought of sending Diahann Carroll a fan letter. When I finally did, trying a number of addresses found online, it kept getting returned. I still listen to the original cast album of No Strings every now and then … Diahann Carroll died in 2020 (https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/04/arts/television/diahann-carroll-dead.html). Diahann Carroll (born Carol Diahann Johnson in 1935 in the Bronx, New York), graduated from the High School of Music and Art (highlighted in the movie “Fame“) and majored in sociology at New York University. A professional model at fifteen, her film debut was in Carmen Jones when she was nineteen. She appeared in Broadway shows, including 1954’s Flower Drum Song and 1977’s Same Time, Next Year, was in many movies and even more television shows. Nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress for the 1974 film Claudine she won Broadway’s Tony award in 1962 for No Strings and the Golden Globe for best actress in a TV series in 1969 for Julia.I still listen to the original cast album of No Strings every now and then. …

May 1, 2018 at 3:35 pm

Take Kate on a Honeymoon. Keep the Prius.

May 1, 2018 at 4:00 pm

I thought you completed a course in creative writing, Steve.

keep ’em coming

May 1, 2018 at 4:59 pm

Amazing story! I could just picture everything, you described it so well.

May 1, 2018 at 6:10 pm

Stephen – great stories are made from the minutia of ‘ordinary’ lives and you are spectacularly gifted at recognizing them and presenting them as irresistible entries in your blog. I hope you can keep writing them, and I can keep enjoying them, for a long time to come.

Joel

May 1, 2018 at 8:44 pm

Joel is right on, you make ordinary and even extraordinary events so real. Your car stories remind me of my first car, a red Studebaker convertible, which was great fun and on which I learned to use a stick shift. That was a valuable lifetime skill, second only to touch typing.

May 1, 2018 at 8:48 pm

Paul,

As always, nice to hear from you. And you are very astute, touch typing – which we learned at WWJHS 246 – is the most valuable lifetime skill of all. Do you remember the teacher’s name?

Best wishes.

May 1, 2018 at 9:41 pm

Typing teacher – Mrs.Keller

July 5, 2018 at 11:15 pm

Joel,

Thank you for the generous comment.

May 1, 2018 at 9:05 pm

Some famous author said to his son that he was sorry he wrote such a long letter—he did not have to time to write a short one (I think it was Lord Chesterton). Shakespeare said brevity is the soul of wit. You have a gift for conveying in few words profound wit.

May 2, 2018 at 1:47 am

Max,

So very nice to hear from you. I appreciate your comments. I believe the long-letter writer was Lord Chesterfield. G.K. Chesterton was the English writer who created the Father Brown series of detective stories. Best and warmest wishes.

May 2, 2018 at 10:49 am

I am not a car person at all. The one exception I would make however is the burgundy jaguar featured on ‘Inspector Morse’. Now that is a beautiful car.

May 2, 2018 at 7:50 pm

I have always wondered why you drove a Jaguar and now I know. Your tales are written so well leaning the reader on an interesting ambling path.

Thank you.

May 31, 2018 at 5:27 pm

A born storyteller! Our love to you and Kate.

July 5, 2018 at 9:50 pm

I couldn’t have said the replys better……….

September 6, 2018 at 8:06 pm

I greatly enjoy reading your interesting and so well written stories. Besides, come to our memory (Magda’s and mine) facts from our N.Y. years

October 6, 2019 at 12:53 pm

Once again,Steve, your biography is a terrific read!!!

Your times in both New York and LA provided great opportunities

And your modesty and hesitation are so charmingly depicted

Thanks