The name of the 19th century composer Frédéric Chopin is widely known. His compositions are frequently played on classical music stations, such as WQXR in New York and KUSC in Los Angeles, both of which can be listened to on your home computer. His melodies are also often heard as background in motion pictures.

The name of the 19th century composer Frédéric Chopin is widely known. His compositions are frequently played on classical music stations, such as WQXR in New York and KUSC in Los Angeles, both of which can be listened to on your home computer. His melodies are also often heard as background in motion pictures.

Although Beethoven is the most important musical figure for me, I have always enjoyed, and been moved by, Chopin’s compositions. I was certainly familiar with the name when I started piano lessons at age 12. I was assigned a simplified version of Chopin’s Prelude in E minor. It was, however, long before that when I first heard Chopin’s name. My grandfather loved music, especially classical music and opera, and I likely heard Chopin’s music and name on the radio. One of my most vivid memories of elementary school was the music appreciation class, where the teacher introduced us to the best known themes of many great composers. Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, of course. The Night on Bald Mountain, which we all knew from Disney’s ‘Fantasia.’ Ave Maria. Some of the music we learned with memorable English lyrics contrived just for those classes. Volga Boatman is still in my head.

One of the pieces I distinctly recall hearing, and being thrilled by, was the Chopin Polonaise in A flat major (the “Heroic”). You can see some wonderful renditions of this composition on YouTube; don’t miss the exciting performances by Vladimir Horowitz and Artur Rubinstein (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oWBT6vOKu0Q, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j5ScGtmvSgY ).

My mother, who loved movies, particularly liked to take me to see biographic films. I remember the 1945 film about Chopin, ‘A Song to Remember,’ that we saw when I was six or seven. The popular actor Cornel Wilde played Chopin— he was nominated for an Academy Award for this—and Merle Oberon, who, in 1939, played Cathy in ‘Wuthering Heights,’ was the notorious George Sand.

he was nominated for an Academy Award for this—and Merle Oberon, who, in 1939, played Cathy in ‘Wuthering Heights,’ was the notorious George Sand.

Over the years, I’ve heard other Chopin Polonaises, as well as Preludes, Waltzes and Concertos.

Mazurkas and Nocturnes.

Études and impromptus.

However, in all the years, I could not recall ever hearing the Ballade in G minor, number 1, opus 123. Or any other of the Chopin Ballades (A Ballade is a one-movement instrumental piece with lyrical qualities reminiscent of a song), a style of composition Chopin created. In the past few weeks I have more than made up for that deficiency, listening to many dozens of recordings of the G minor Ballade, a most wonderful, even extraordinary, powerful musical piece, said to be among the most difficult piano pieces to play, perhaps the most difficult.

This recent aural gluttony was prompted by reading “Play It Again – An Amateur Against the Impossible” by Alan Rusbridger, published in 2013, when Rusbridger was editor-in-chief of the renowned London newspaper, The Guardian.  Despite the suggestive title, the book has nothing to do with Casablanca, Bogart, Bergman or, for that matter, Dooley Wilson. Instead, the book tells the story, as Rusbridger recorded in his diary, of his determination, at the age of 53, to learn, in a year’s time, to fluently play the Chopin G minor Ballade despite, his never having been an accomplished pianist and despite not playing seriously since he was a teenager. Intermixed with his musical comments are tales of the dynamic events of that period, including his close involvement with the Wikileaks crisis involving Julian Assange, Rupert Murdoch and others. At the same time, he decided to build a music room at his country home, Fish Cottage, in Blockley, two hours north of London. He also recounts his efforts to buy a new grand piano. The book is full of fascinating tales as Rusbridger relates these four distinct, but related, themes: the struggle to learn the G minor Ballade, the events of the times as they related to his role as editor of The Guardian, the construction of the addition to Fish Cottage and the identification and purchasing of a new piano.

Despite the suggestive title, the book has nothing to do with Casablanca, Bogart, Bergman or, for that matter, Dooley Wilson. Instead, the book tells the story, as Rusbridger recorded in his diary, of his determination, at the age of 53, to learn, in a year’s time, to fluently play the Chopin G minor Ballade despite, his never having been an accomplished pianist and despite not playing seriously since he was a teenager. Intermixed with his musical comments are tales of the dynamic events of that period, including his close involvement with the Wikileaks crisis involving Julian Assange, Rupert Murdoch and others. At the same time, he decided to build a music room at his country home, Fish Cottage, in Blockley, two hours north of London. He also recounts his efforts to buy a new grand piano. The book is full of fascinating tales as Rusbridger relates these four distinct, but related, themes: the struggle to learn the G minor Ballade, the events of the times as they related to his role as editor of The Guardian, the construction of the addition to Fish Cottage and the identification and purchasing of a new piano.

In order to accomplish his exceedingly ambitious musical goal Rusbridger studied with a number of experienced teachers. He also interviewed many fine pianists of the day including Emanual Ax, Alfred Brendel, Murray Perahia, Martha Argerich and others. In detailing his piano purchase efforts, he taught me much I didn’t know about piano companies and their products, including some apparently fine piano brands I never knew. I’d heard of Bechstein, Kamai and Yamaha but was not familiar with Danemann or Fazioli. Rusbridger describes the construction of pianos in general and of his piano in particular. Did you know the Steinway piano company in Germany owns the forest from which it obtains the wood for the pianos made in Munich?

As I enjoyed this rich, charming and captivating book I listened, and often relistened, to a host of pianists playing the G minor Ballade. I also watched videos of dozens of live performances of the same piece.

The G minor Ballade is, as I learned, dauntingly difficult to play. It is, also, a piece that challenges the ear; in no way can it be considered ‘easy listening.’ I soon came to appreciate, however, that listening to the G minor Ballade is, without any doubt, more than worth the effort.

As I listened to the piece for what I thought was the first time, I immediately recognized some of the themes of the G minor Ballade. I had, indeed, heard it before, or at least parts of it, over the years. If you saw Roman Polanski’s excellent 2002 film, ‘The Pianist,’ you also have heard this great music. The movie is based on the autobiography of  Wladyslaw Szpilman, a Polish-Jewish pianist who was in Warsaw after the invasion and occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany. Szpilman escapes from a concentration camp and makes his way back to the now-destroyed Warsaw Ghetto. He wanders around looking for food and is captured by Wehrmacht officer Wilm Hosenfeld. When Hosenfeld, himself a pianist, hears of Szpilman’s career, he takes him to a deserted home where a piano still stands and forces Szpilman to play. The decrepit, starving pianist plays the Ballade in G minor. Hosenfeld then (“spoiler alert”) allows Szpilman to hide in the attic of the house and supplies him with food until the end of the war.

Wladyslaw Szpilman, a Polish-Jewish pianist who was in Warsaw after the invasion and occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany. Szpilman escapes from a concentration camp and makes his way back to the now-destroyed Warsaw Ghetto. He wanders around looking for food and is captured by Wehrmacht officer Wilm Hosenfeld. When Hosenfeld, himself a pianist, hears of Szpilman’s career, he takes him to a deserted home where a piano still stands and forces Szpilman to play. The decrepit, starving pianist plays the Ballade in G minor. Hosenfeld then (“spoiler alert”) allows Szpilman to hide in the attic of the house and supplies him with food until the end of the war.

The G minor Ballade is a highly complex, magnificent, work. Before it surrenders its treasures—and this composition is packed with treasures for the ears and, even more, for the mind—you have to put in some work. The more you listen to it the more you will hear and the more you will cherish.

In the beginning I listened to the music while I was reading the book. That didn’t work. I soon realized, despite having the piece playing multiple times, I had not yet heard it.

I began again, without the book, mostly using the Apple Music app to search. This yielded 22 different performers with a total of 36 performances, all of which I listened to. If you Google ‘Chopin Ballade Number 1’ you will get 1,720,000 hits, a far too intimidating number. Consequently, I tried YouTube, which has links to many videos of performances of the piece. Do it! Allow yourself to be mesmerized by Artur Rubinstein, Vladimir Horowitz, and countless others. You can even choose the YouTube audio performance by the legendary Josef Hofmann, called the greatest pianist of all time.

The performances are between 8 and 9 minutes long, depending on the pianist. In that short period you will hear sounds that are restful, melodic, thrilling, sad, exhilarating, somber, and triumphant. And more, affirming the intrigue of the G minor Ballade. The same performer will play it differently over time. Try it! You’ll like it!

This link (http://pianoteachernorthlondon.com/reviews/chopin-ballade-no-1-interpreters/) will let you sample some breathtakingly beautiful performances, starting with Maurizio Pollini and including Horowitz, Rubinstein and Murray Perahia. There are two versions, years apart, by Vladimir Ashkenazy. Many other pianists can be seen, each with their nuanced performance, each worth listening to. You can find the marvelous Krystian Zimerman rendition on a separate YouTube link (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Thpa0M2SCaU).

Two of the great romantic figures of the 19th century were Franz Liszt (1811-1886) and Frédèric Chopin. The were both composers and virtuoso pianists.

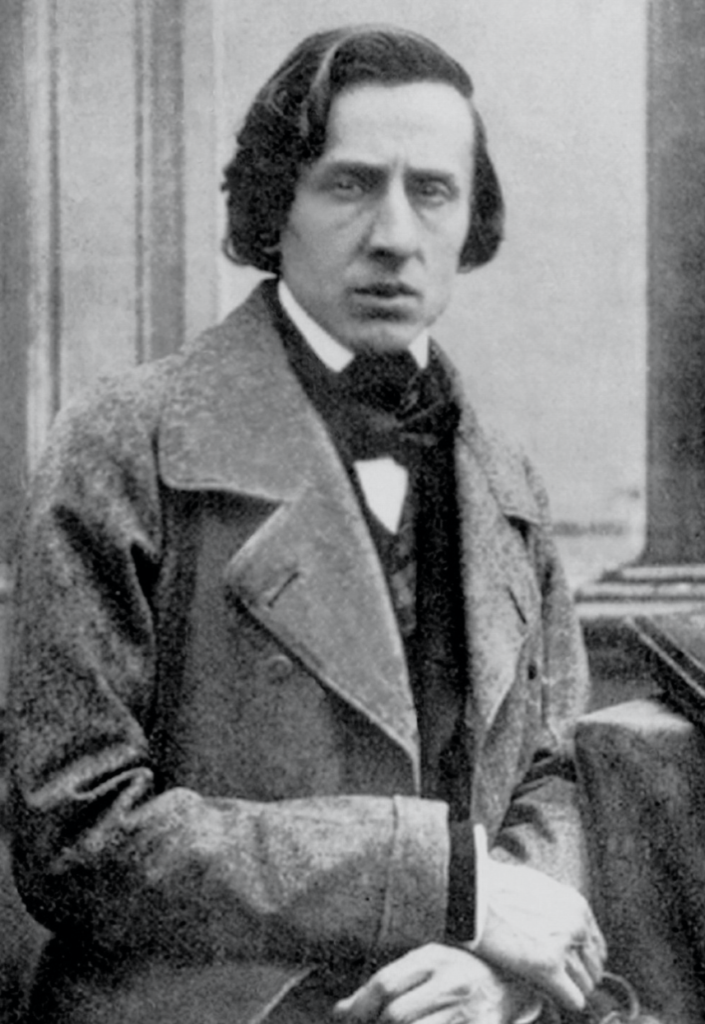

Frédèric Francois Chopin, born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin (1 March 1810 – 17 October 1849) was raised in Warsaw. He left Poland for political reasons and, after confronting difficulties in attempts to move to various countries, finally settled in Paris at the age of 21. He wrote mostly for the solo piano and, for the last 18 years of his life, supported himself by selling his compositions and giving piano lessons, performing only 30 times in public. This was in contrast to his friend Liszt who, until his last years, was always in the public eye.

Liszt was widely regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time. Born in Hungary, he and his parents moved to  Paris when he was 16. A recognized musical prodigy before he was eight, Liszt knew Haydn, Hummel and Beethoven. Liszt’s ten-year relationship with the married Countess Marie d’Agoult yielded two daughters (one of whom, Cosima, would eventually marry Richard Wagner) and then a son. A few years after parting with Marie d’Agoult, he began a decades-long romance with the also wed Polish Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein. They wanted to marry but were prevented from doing so by the intervention of the Pope himself, instigated by Carolyne’s husband and the Tsar of Russia. Liszt achieved great professional success and was renowned for his generosity. He counted Chopin, only a year older, as a close friend and one of the most important influences on his career. Liszt died at the age of 74.

Paris when he was 16. A recognized musical prodigy before he was eight, Liszt knew Haydn, Hummel and Beethoven. Liszt’s ten-year relationship with the married Countess Marie d’Agoult yielded two daughters (one of whom, Cosima, would eventually marry Richard Wagner) and then a son. A few years after parting with Marie d’Agoult, he began a decades-long romance with the also wed Polish Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein. They wanted to marry but were prevented from doing so by the intervention of the Pope himself, instigated by Carolyne’s husband and the Tsar of Russia. Liszt achieved great professional success and was renowned for his generosity. He counted Chopin, only a year older, as a close friend and one of the most important influences on his career. Liszt died at the age of 74.

Chopin also had a number of well-known romances, including a complicated, tempestuous, and ultimately unhappy, relationship with George Sand (Amantine Lucille Aurora Dupin), who wrote more than 50 novels and was notorious for insisting on wearing men’s clothes. Under five feet, big-eyed, dark, Sand smoked cigars and initially repelled  Chopin. Eventually, they became lovers. Chopin and Sand, who were painted by Chopin’s close friend Eugène Delacroix, and Sand’s two children, spent a miserable winter of 1938-39 in Majorca where the traditionally Catholic people treated the unmarried couple poorly and made it hard for them to find accommodations. Their relationship lasted ten years but ended in 1847 after exchanges of angry correspondence.

Chopin. Eventually, they became lovers. Chopin and Sand, who were painted by Chopin’s close friend Eugène Delacroix, and Sand’s two children, spent a miserable winter of 1938-39 in Majorca where the traditionally Catholic people treated the unmarried couple poorly and made it hard for them to find accommodations. Their relationship lasted ten years but ended in 1847 after exchanges of angry correspondence.

For most of his life, Chopin was in poor health. Whereas Liszt lived a long and prosperous life, Chopin died destitute, in Paris, at age 39. A photograph shows Chopin just months before he died and a painting depicts him on his deathbed.  He had long suffered from tuberculosis which became widely disseminated, including involving the outer heart (pericarditis), not unusual in those times. His funeral, including an elaborate musical celebration with orchestra and chorus, who played some of his compositions, was paid for by his former pupil and friend, Jane Stirling, a Scottish heiress.

He had long suffered from tuberculosis which became widely disseminated, including involving the outer heart (pericarditis), not unusual in those times. His funeral, including an elaborate musical celebration with orchestra and chorus, who played some of his compositions, was paid for by his former pupil and friend, Jane Stirling, a Scottish heiress.

All of Chopin’s compositions include the piano. Most are for solo piano, although he wrote two piano concertos and piano pieces that included other instruments.

Although he died more than 150 years ago, Chopin’s grave in Père Lachaise cemetery is continuously decorated with fresh flowers. If you have never been to Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris you have missed one of Paris’s greatest  treasures. Here you can see the tombs of some of the most renowned figures of history. Many of the memorials, of the famous and the not so famous, are exquisitely beautiful. In many ways, Père Lachaise ranks with the most wonderful sculpture museums of the world. A few of the more than 300,000 graves at Père Lachaise—Sarah Bernhardt, Edith Piaf, Jim Morrison, as well as Chopin’s—are also constantly adorned with fresh flowers.

treasures. Here you can see the tombs of some of the most renowned figures of history. Many of the memorials, of the famous and the not so famous, are exquisitely beautiful. In many ways, Père Lachaise ranks with the most wonderful sculpture museums of the world. A few of the more than 300,000 graves at Père Lachaise—Sarah Bernhardt, Edith Piaf, Jim Morrison, as well as Chopin’s—are also constantly adorned with fresh flowers.

As I listened to the Artur Rubinstein performance I was reminded of the time Kate and I almost met the great pianist, renowned for his interpretations of Chopin’s music. In the middle years of the 20th century the two great American pianists were Vladimir Horowitz and Artur Rubinstein. They were very different. Horowitz has been described as a neurotic recluse whose public appearances were relatively few and far between. In contrast, Rubinstein was an indefatigable bon vivant who lived to give public concerts.  His performances were known for their lyricism and verve as well as his distinctly rich and warm tone. He was also an enthusiastic music collaborator playing in chamber music groups and with the greatest orchestras. Born in Lodz, Poland, in 1887, he became the 20th century avatar of Chopin’s music, expressing fully its strength and its poetry. In late 1970, Rubinstein was scheduled to perform in Charleston, South Carolina. We were living one hour south of Charleston, in Beaufort, South Carolina (the city Beaufort in North Carolina is pronounced in the French way as ‘Bo-for’ but the one in South Carolina is pronounced ‘Bewferd’). I was in the second year of service at the Naval Hospital, Beaufort, S.C. and I ordered tickets for us. Although South Carolina was initially akin to Mars for these Brooklyn- and Nyack-born migrants, Kate luckily met an amazing woman, Harriet Keyserling, and we both subsequently became

His performances were known for their lyricism and verve as well as his distinctly rich and warm tone. He was also an enthusiastic music collaborator playing in chamber music groups and with the greatest orchestras. Born in Lodz, Poland, in 1887, he became the 20th century avatar of Chopin’s music, expressing fully its strength and its poetry. In late 1970, Rubinstein was scheduled to perform in Charleston, South Carolina. We were living one hour south of Charleston, in Beaufort, South Carolina (the city Beaufort in North Carolina is pronounced in the French way as ‘Bo-for’ but the one in South Carolina is pronounced ‘Bewferd’). I was in the second year of service at the Naval Hospital, Beaufort, S.C. and I ordered tickets for us. Although South Carolina was initially akin to Mars for these Brooklyn- and Nyack-born migrants, Kate luckily met an amazing woman, Harriet Keyserling, and we both subsequently became  friends with her and her husband, Dr. Herbert Keyserling. Herb was one of the most capable doctors I ever met, even after I spent the previous four years at The Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, where you could not turn a corner without bumping into a deservedly renowned and brilliant physician. His warm and witty autobiography, “Doctor K,” tells of his distinguished family (his older brother, Leon, an economist, was Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors to President Harry Truman and was hounded out of government service in the infamous McCarthy years) and of his life as a general practitioner in Beaufort. He met his wife, Harriet, the daughter of a New York City dentist, when he was in New York for a residency before joining the U.S. Navy. Herb served in World War II, including at Guadalcanal, the site of one of the bloodiest battles, where he earned the Silver Star for ‘gallantry in action.’ Harriet, a Barnard graduate, was the cultural center of Beaufort. She became politically active and eventually served eight terms in the South Carolina House of Representatives. Her autobiography is “Against the Tide: One Woman’s Political Struggle.” At Harriet’s on a Sunday afternoon we might hear a young musician from the university perform or enjoy an Ingmar Bergman film (the movie house in town tended to alternate John Wayne films with those of Elvis Presley). The Keyserling house was a restorative cultural oasis. We were once at a social gathering at Harriet’s house and mentioned we were going to see Rubinstein. Harriet told us she was also planning to go to the concert and, further, she knew Rubinstein very well. If I didn’t mind driving her, she would take us backstage to meet him after the concert. I was so excited— I had long been a fan of Rubinstein’s—and literally counted the days until the concert. Unfortunately, Harriet developed a cold the morning of the concert and could not go. We, of course, went anyway. The concert was, as expected, marvelous but, alas, we never met the great Rubinstein.

friends with her and her husband, Dr. Herbert Keyserling. Herb was one of the most capable doctors I ever met, even after I spent the previous four years at The Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, where you could not turn a corner without bumping into a deservedly renowned and brilliant physician. His warm and witty autobiography, “Doctor K,” tells of his distinguished family (his older brother, Leon, an economist, was Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors to President Harry Truman and was hounded out of government service in the infamous McCarthy years) and of his life as a general practitioner in Beaufort. He met his wife, Harriet, the daughter of a New York City dentist, when he was in New York for a residency before joining the U.S. Navy. Herb served in World War II, including at Guadalcanal, the site of one of the bloodiest battles, where he earned the Silver Star for ‘gallantry in action.’ Harriet, a Barnard graduate, was the cultural center of Beaufort. She became politically active and eventually served eight terms in the South Carolina House of Representatives. Her autobiography is “Against the Tide: One Woman’s Political Struggle.” At Harriet’s on a Sunday afternoon we might hear a young musician from the university perform or enjoy an Ingmar Bergman film (the movie house in town tended to alternate John Wayne films with those of Elvis Presley). The Keyserling house was a restorative cultural oasis. We were once at a social gathering at Harriet’s house and mentioned we were going to see Rubinstein. Harriet told us she was also planning to go to the concert and, further, she knew Rubinstein very well. If I didn’t mind driving her, she would take us backstage to meet him after the concert. I was so excited— I had long been a fan of Rubinstein’s—and literally counted the days until the concert. Unfortunately, Harriet developed a cold the morning of the concert and could not go. We, of course, went anyway. The concert was, as expected, marvelous but, alas, we never met the great Rubinstein.

Right now, as I type this, I am again listening to the G minor Ballade, intrigued by what music makes us feel as we listen to it. There is literature about this topic in psychology and musicology texts and journals as well as online. One of the most detailed studies (Lansdale AJ, North AC. ‘Why do we listen to music? A uses and gratifications analysis’. British Journal of Psychology, 2011;102:108), lists 30 reasons (e.g. to help get through difficult times, to make one feel better, to relax, to escape the reality of everyday life, to spend time with friends, etc), most of which do not exactly explain why I listen to music or, particularly, why I have come to love the Chopin G minor Ballade. This music transports me to a place where my conscious does not reside. Rather than escaping, I enter a unique world that only music creates. A few performers leave a slightly long period of time between the opening phrase of the G minor Ballade and the next section of the piece and, at that moment, in those playings, I get the feeling of being poised at the top of a roller coaster track just before it races downward. It is anticipatory, anxious and thrilling. I am suspended at the edge of a precipice ready to be taken somewhere exciting and mysterious. In contrast, in some of the quiet sections I am thrilled because of the intensity, almost painful, of the beauty flowing out of those black and white keys. Each time I listen the music seems, wonderfully, a little different.

Different with each pianist. Different with each playing. Different with each listening.

October 12, 2020 at 5:50 pm

Dr Geller

oustanding text.

I would like adding one question. I asked once to one of my patients (he was a conductor) – Why some musics makes us cry not of joy or suffering, but for a profound emotion we do not feel with other art manifestations. He answered me – that’s the signal you entered the composer’s soul. So far I don’t know if he overreacted

October 13, 2020 at 3:39 pm

I like his answer very much!

October 12, 2020 at 6:13 pm

Thank you for sharing! Very well written essay! I learned a lot!

October 12, 2020 at 7:25 pm

I DO NOT REMEMBER EVER HEARING U PLAY THE PIANO IN BKOOLYN OR VALLEYSTREAM…………AS USUAL YOUR POST WAS VERY THROUGH….

October 12, 2020 at 8:29 pm

Reminded me of going to Radio City Music Hall with my parents as a little girl. Your articles always take me on a wonderful journey!

October 12, 2020 at 10:18 pm

I wonder if Cosima and Wagner had kids and if any of their ‘musical’ genes were transcribed. Speaking of transcription, you might enjoy a lovely Chopin piano piece, nocturne in C minor, transcribed to the violin and played by Itzhak Perlman. It might take you on a smaller roller coaster ride:

https://youtu.be/t4JPHah7V5M

October 12, 2020 at 11:49 pm

Upon leaving the opera La Boheme I still had tears in my eyes. My husband asked, “why is it that you only cry at concerts, not in real life?” I could not answer then but I feel that music actually can effect the body. There are certain chords, for example, that some how just touch your organs, as much as your soul.

October 13, 2020 at 8:46 am

I’m working now on two Chopin nocturnes and one prelude. The experience brings greater appreciation.

October 13, 2020 at 3:19 pm

Dear Stephen, breathtaking reading even for, or just for the less educated in this music.Congratulation. I start to be an admirer too

October 13, 2020 at 10:57 pm

A LOT OF WORK WENT INTO THIS PIECE. Particularly interesting that Beaufort and Charleston are mentioned. Keep on writing this entertaining stuff.

October 14, 2020 at 3:55 pm

Loved essay on Chopin. Will take your advice on the Ballad.Saw the movie.So sad that someone who created so much beauty had such a sad short life. Diana

October 15, 2020 at 5:26 pm

Being on Covid “house arrest” I look forward to listening to 20 or 30 versions of the Ballade. Thanks so much for the commentary.

October 16, 2020 at 12:42 pm

Enjoy!

October 17, 2020 at 3:48 pm

Chopin’s “Heroic” Polonaise was quite familiar when I listened to it. Once again you have energized my dormant ‘classical’ interests with one of your wide ranging and well presented discourses. Keep on!